Temporal Dimensions and Differentiation of Export Controls: Evidence from the Global Trade Alert Database

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #78

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #78

Recent announcements of Chinese export controls on rare earths have kept trade analysts busy in determining the magnitude of such policy measures. While 2025 has been exceptional in terms of Chinese export control incidence, it has not been unprecedented. This piece investigates the temporal dimensions and differentiation of various types of export controls introduced by China, the United States and EU27. I focus exclusively on interventions introduced on a single-jurisdiction basis: export bans, export quotas, export taxes, export tariff quotas, export licensing requirements, export-related non-tariff measures, export price benchmarks, and local supply requirements for exports, isolating core export instruments from wider trade policy tools.

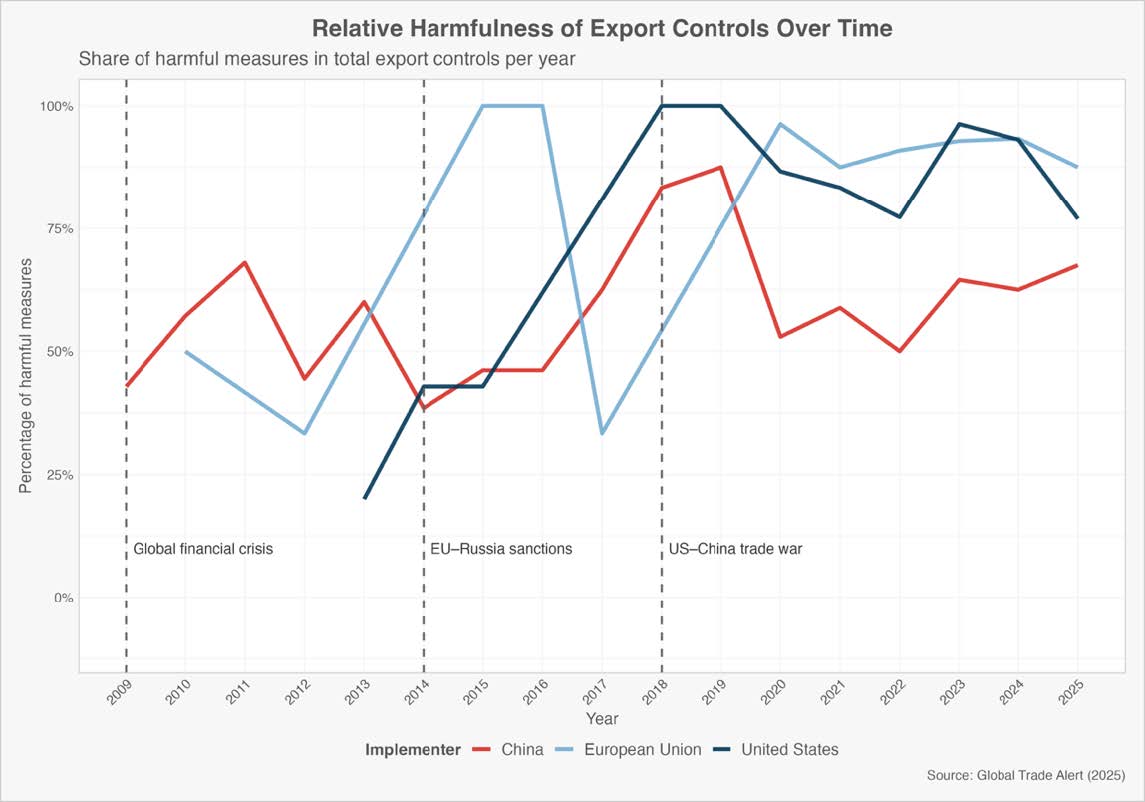

Figure 1 shows the share of export barriers over total export policies in the GTA database for China, the United States and EU27 since 2009. We observe that there export controls have been used more frequently across all three economies since 2018. China’s share of harmful measures has been rising steadily since 2014, with a notable peak at the onset of the US-China trade war in 2018 and a sizable downward revision during the Covid-19 pandemic to pre-trade war levels. The United States shows a sustained increase in harmful measures after 2018, reflecting its shift towards a new industrial policy and trade barriers. The EU27 reflects this shift to more harmful measures in export controls, with strong fluctuations, due to geoeconomic considerations targeting China, the United States and Russia. Together, these patterns suggest that export controls are used increasingly systematically rather than on an ad hoc basis.

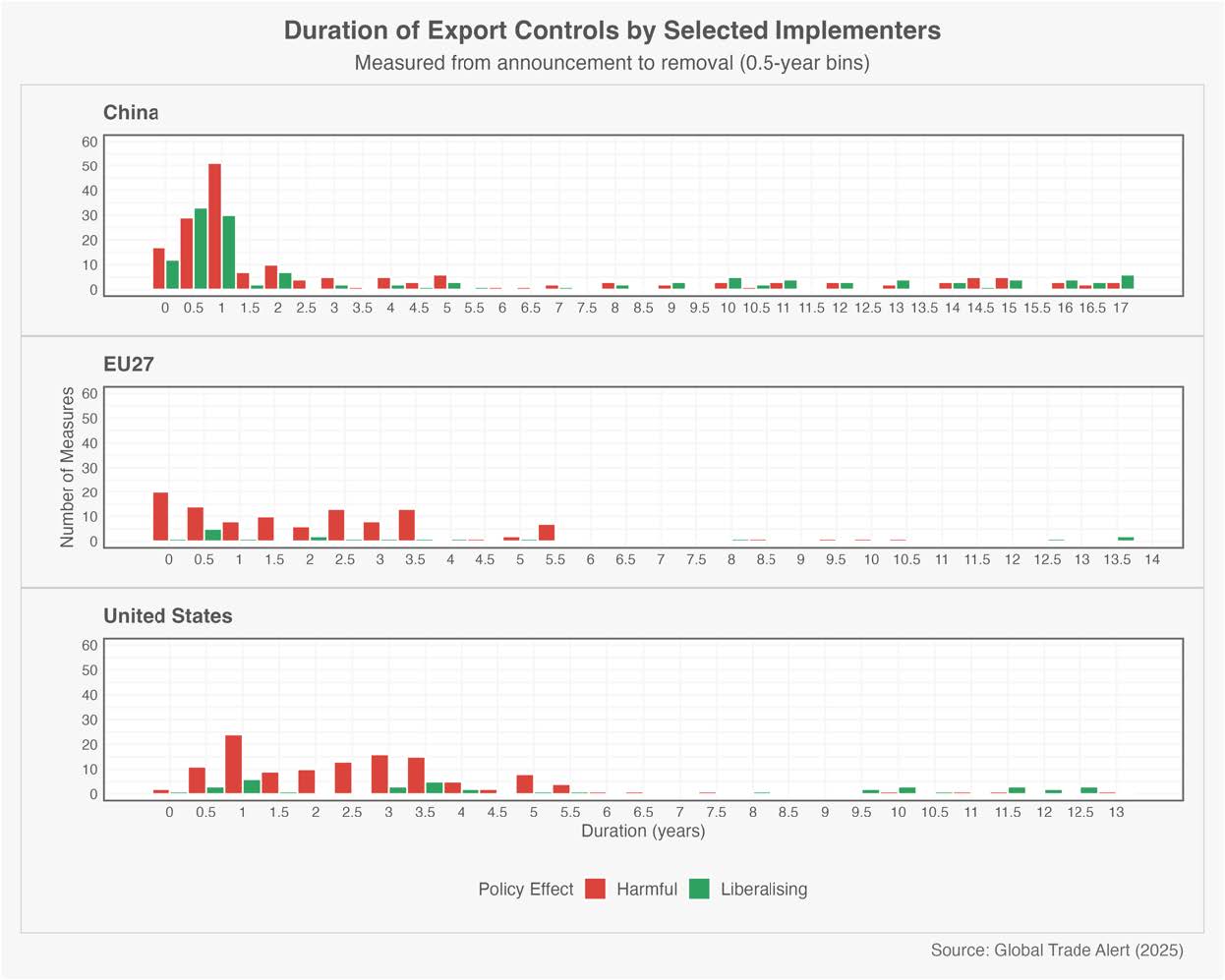

Figure 2 compares the distribution of concluded export controls by duration (6-month bins) by harmful vs. liberalizing measures. China’s distribution is strongly skewed toward short-term measures, showcasing its preference for time-constrained interventions. The United States and European Union display a flatter distribution with smaller peaks within the first five years post-announcement, while also having long-term moats in liberalizing measures at 12.5 – 13.5 years (USA) and 11.5-12.5 years (EU27). Figures 1 and 2 suggest that export controls are becoming more frequent, more harmful, and, depending on the implementer, more short-term (China) vs. embedded in longer-term strategies (USA; EU27).

In total, Chinese export controls make up most interventions (N=318) out of which almost two thirds are harmful measures. Most Chinese measures are short-lived, with a median duration of around one year for harmful and liberalizing measures respectively, considerably lower than the United States (2.5-4 years) and the EU27 (1.9-2.2 years). These differences highlight diverging policy logics since China uses export controls as flexible instruments, frequently adjusted or withdrawn, while the United States and EU27 use them as regulatory or sanction-based mechanisms integrated into policy frameworks.

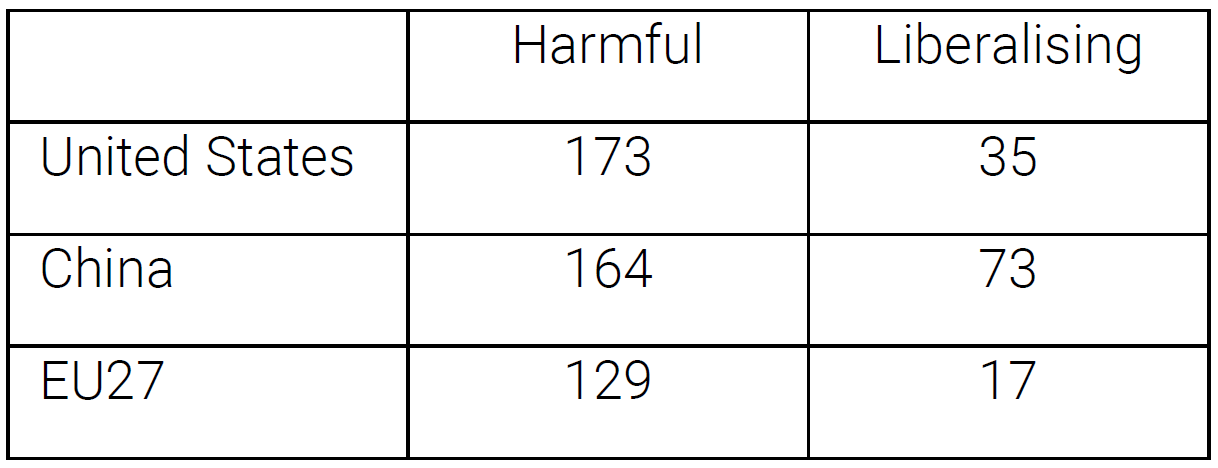

Additionally, there are currently 591 active export controls (compared to 606 concluded measures) in which the United States and China hold a similar of harmful measures but China showing a much higher level of ongoing liberalising measures, indicating a more balanced policy mix compared to the more restrictive United States and EU27.

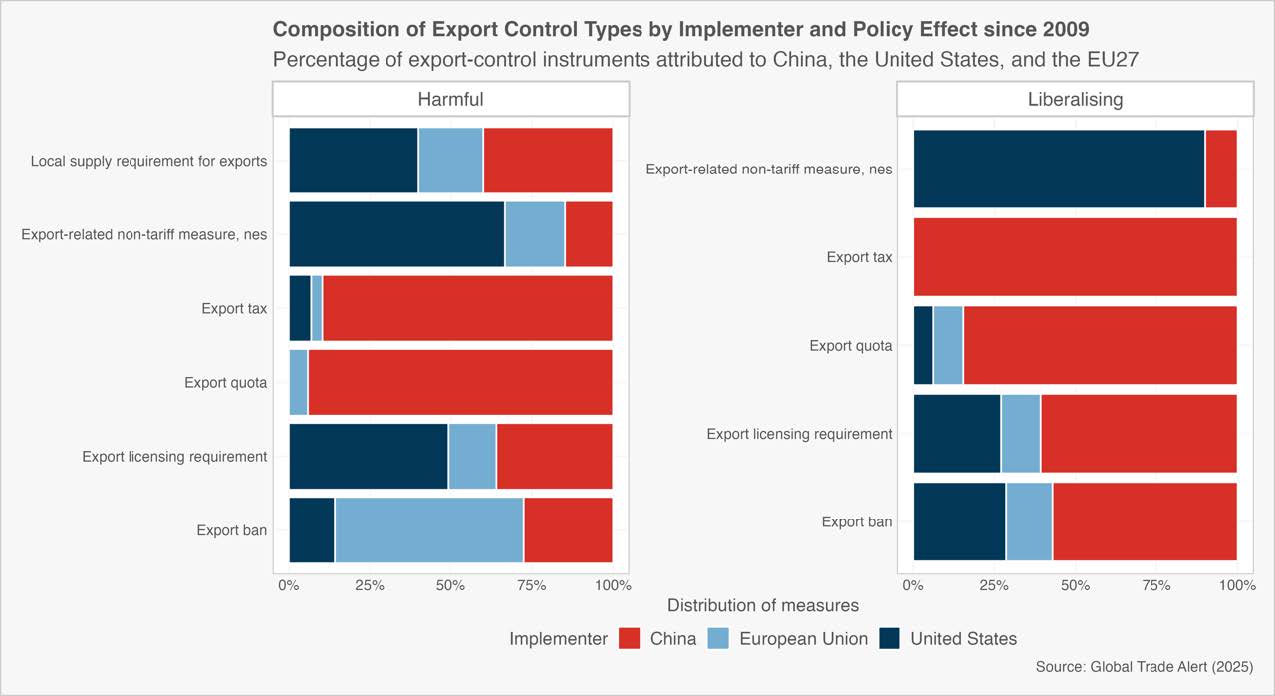

Figure 3 compares types of export control measures by implementer, grouped by harmful and liberalizing interventions. Across all measures, China accounts for around 46% of total single-jurisdiction export-control interventions, followed by the United States at 29% and the EU27 at around 25%. Among harmful interventions, the United States and China are responsible for almost three-quarters of all restrictive export controls at 31.7% and 42.5% respectively. The EU27 represents 25.8%, reflecting a more selective use of export restrictions. The disaggregated data, therefore also shows functional differences between both assessment types and jurisdictions.

Harmful measures are dominated by ‘traditional’ instruments like export bans, quotas, licensing requirements, and non-tariff measures (NTMs), especially favored by the United States and EU27. By contrast, China’s harmful interventions rely mainly on export taxes and quotas, measures that can easily be scaled. In contrast, liberalizing export controls (easing or suspending restrictions) are largely concentrated in China, which accounts for over 70% of all liberalizing interventions. The United States follows with about 20% and the EU27 with 9%. For liberalizing export control measures, China mainly employs export taxes and quotas but also makes heavy use of licensing requirements by updating its export ban lists. The United States and EU27 mainly employ NTMs, licensing requirements, and export bans.

The presented descriptive evidence suggests several implications for trade policy and global value chains:

China’s export controls appear increasingly aligned with its strategic and industrial policy goals, especially for critical minerals and high-tech inputs.

Chinese measures are shorter than US and EU export controls, yet the timing and precision imply that their immediate impact on downstream supply chains may compensate the ‘lack’ in duration, as was the case with the October 9 announcement of export controls on critical raw materials.

Longer, but less frequent export controls used by the US and EU reflect different modalities. Using similar measures to China, both economies use wider trade and security strategies, like the US’ export controls on advanced semiconductors to boost competitiveness or the EU’s dual-use regulation on chemicals.

The rising shift in trade barriers such as export controls reflects the wider shift in the global economy away from export facilitation policies, making export controls new tools in conducting trade policy.

To sum, by focusing on the duration and temporal evolution instead of the incidence of sectoral questions, the data show that export controls became popular policy instruments across large economies. For China, this means the use of frequent, short-term, and strategic controls. The United States and EU27, however, apply fewer but more persistent controls. Policymakers should use this information to understand the potential and implications of newly introduced export controls and the effect that reciprocal policy measures by the respective counterparts may have on their economies.

Angelo Gerber-Helm is a Junior Data Analyst at the Global Trade Alert and a PhD Researcher at the Geneva Graduate Institute