Government is Back in Business

The Global Trade Alert today releases five new intervention types that round out our existing taxonomy of state loans, loan guarantees, and financial grants.

Ana Elena Sancho, Johannes Fritz

04 Feb 2026

The Global Trade Alert today releases five new intervention types that round out our existing taxonomy of state loans, loan guarantees, and financial grants.

Ana Elena Sancho, Johannes Fritz

04 Feb 2026

The Global Trade Alert today releases five new intervention types. These join our existing categories—state loans, loan guarantees, and financial grants—to create a nine-instrument taxonomy of state capitalism. The new categories distinguish direct government subsidies from support channelled through financial intermediaries. This refinement enables sharper analysis: tracking not just what governments spend, but how they structure their support. This differentiation matters for two reasons.

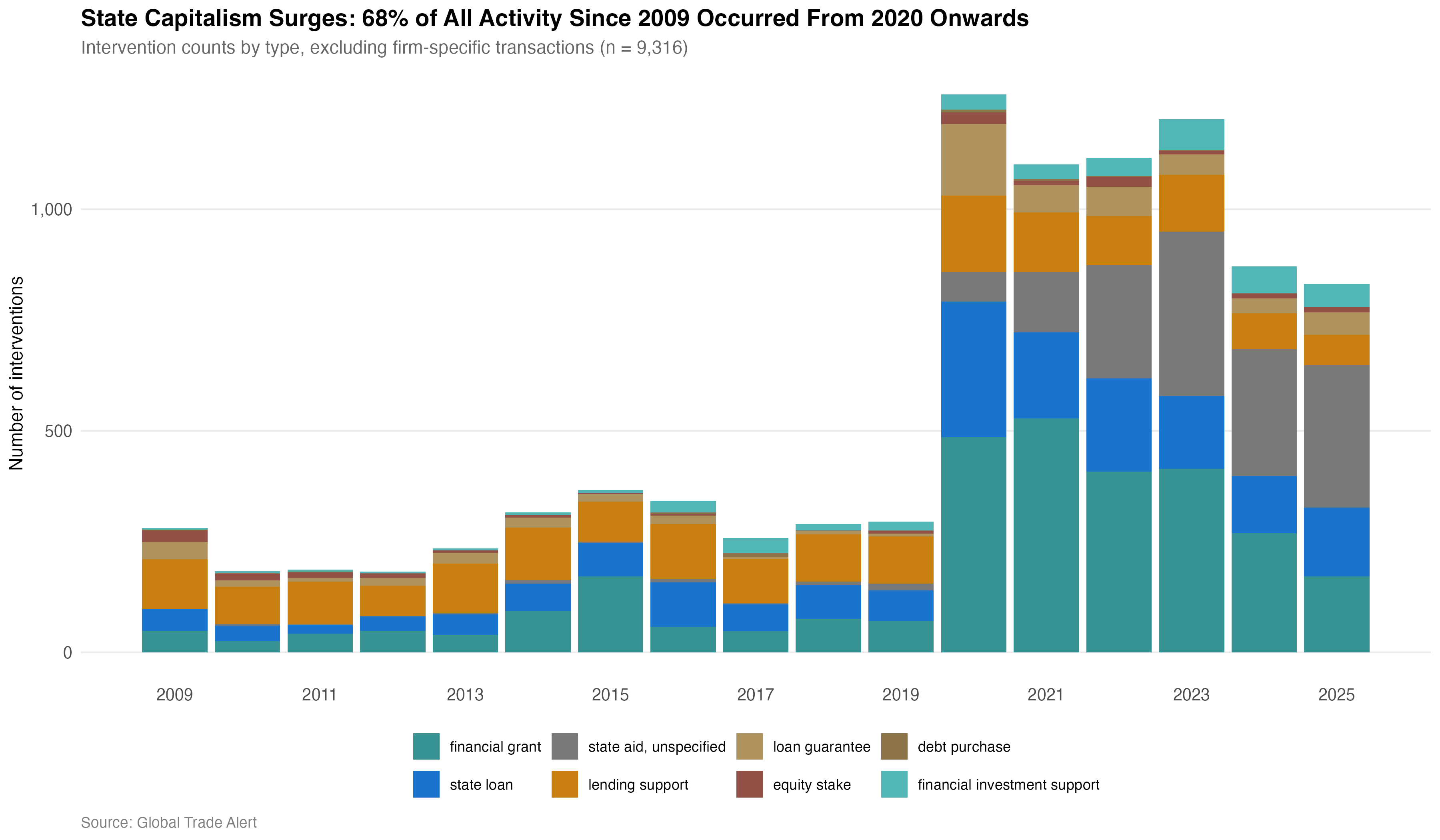

First, volume. Since 2009, 68% of all recorded subsidy programmes were implemented from 2020 onwards. State capitalism has surged.

Second, opacity. Governments increasingly channel support through commercial facades. When state backing flows through financial intermediaries rather than treasuries, tracking becomes difficult and effectiveness assessment nearly impossible.

The new taxonomy separates direct interventions—where government acts on its own balance sheet—from intermediated support where state backing flows through designated financial institutions.

Direct interventions:

Intermediated support:

State loans, loan guarantees, financial grants and state aid unspecified remain as separate categories, providing continuity with prior GTA analysis. The new types capture forms of support that were previously scattered or unclassified.

Our analysis of 9,316 programme-level interventions reveals three patterns that will guide this analytical series.

Annual subsidy activity quadrupled from 2020 onwards. The 2020–2025 period concentrates 68% of all recorded programmes despite covering only six of the database's seventeen years.

The surge appears across all intervention types, but composition shifted. Financial grants (the teal bars dominating 2020) declined as lending support and state loans rose. This pattern indicates governments moved from emergency disbursements to structured financing.

Among G20 members, Brazil, Canada, China, Mexico, and South Korea recorded higher counts in 2025 than in 2020, indicating that current activity levels exceed their 2020 baseline.

A different pattern emerges elsewhere. Argentina, Russia, and the United States rebounded in 2023. Russia and the US now record more subsidies than during the early pandemic years.

Lending support, financial investment support, and state aid, unspecified together, represent 40% of all recorded interventions. These are the most opaque forms of state capitalism. Intermediary support alone accounts for nearly one quarter of all programmes.

Lending support now exceeds direct state loans and loan guarantees in frequency. Because this support operates through multiple institutional layers, attribution becomes systematically harder. State backing no longer flows directly from government to beneficiary. When intermediaries are private financial institutions, credit extended with government backing appears identical to commercial lending.

The 'unspecified' category deserves particular attention. These are interventions where governments announce support without clarifying the delivery mechanism.

Consider three examples. When China's State Council adopts guidelines on 'strengthening financial support for strategic economic sectors', the document commits billions without specifying whether funds will flow as grants, loans, equity, or guarantees. When Cambodia launches a USD 300 million stimulus package to help businesses recover from COVID-19, the government provides a 'financing fund' without detailing the instrument. When the UK announces GBP 43 million for broadband deployment in Cheshire, the funding agency 'did not specify the type of funding'.

This opacity benefits governments whether deliberate or not. State aid unspecified makes tracking harder and trade policy responses difficult to calibrate. A trading partner cannot challenge what it cannot characterise.

Public financial institutions channel 37% of recorded subsidies globally, but this share ranges from 74% in Brazil to under 1% of domestic programmes in the United States.

Brazil routes nearly three-quarters of its subsidies through institutions like the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). France channels 39% through public financial institutions, Germany 31%, the United Kingdom 29%, and Japan 21%. China, despite its state-dominated economy, routes only 2% through identified public financial institutions—suggesting either genuine reliance on direct government channels or systematic under-reporting of intermediary involvement. We will return to our tracking of Chinese government actions in a separate piece.

The United States presents a stark contrast to Brazil. Over 99% of recorded domestic subsidy activity originates at federal and state government levels. American public financial institutions focus narrowly on export finance through the Export-Import Bank, which is excluded from domestic subsidy counts presented here. This pattern may shift: the Trump administration has signalled interest in expanding development finance tools, potentially utilising the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) or similar vehicles for domestic industrial policy.

The institutional variation matters for trade policy. Subsidies flowing through development banks are harder to identify, slower to challenge, and more difficult to quantify than direct budget transfers. Countries that route support through intermediaries gain systematic advantages in subsidy disputes.

This analytical series will examine each intervention type in detail. The next piece covers direct government interventions such as debt purchases and equity stakes; tracking which countries use these instruments, what sectors they target, and how patterns evolved over time.

Subsequent analyses examine intermediated support: the lending programmes and financial investment vehicles that now dominate state capitalism's toolkit. A third part focuses on the original GTA intervention types, including financial grants and direct state lending.

Using this new taxonomy, we will deepen our coverage of the major trading blocs to provide an increasingly comprehensive description of state capitalism as the year progresses.

The database refinement announced today makes these analyses possible. By distinguishing how governments structure their support, not just what they spend, the Global Trade Alert provides the granularity that trade policy analysis requires.

Full documentation for the new taxonomy, including detailed definitions and coding guidance, is available in the updated GTA Handbook.

A methodological note explaining the taxonomy update is available at https://globaltradealert.org/blog/state-capitalism-taxonomy-update.