Can Trading Partners Still Hedge? U.S. Poison Pills and the Limits of Dual Engagement

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #77

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #77

The United States has incorporated restrictive third-country provisions—informally referred to as “poison pills”—in three trade instruments: the 2018 United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), and very recently the 2025 United States-Malaysia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade (ART), and the 2025 United States-Cambodia ART. These provisions allow the United States to terminate agreements if partner countries conclude trade arrangements with certain third countries.

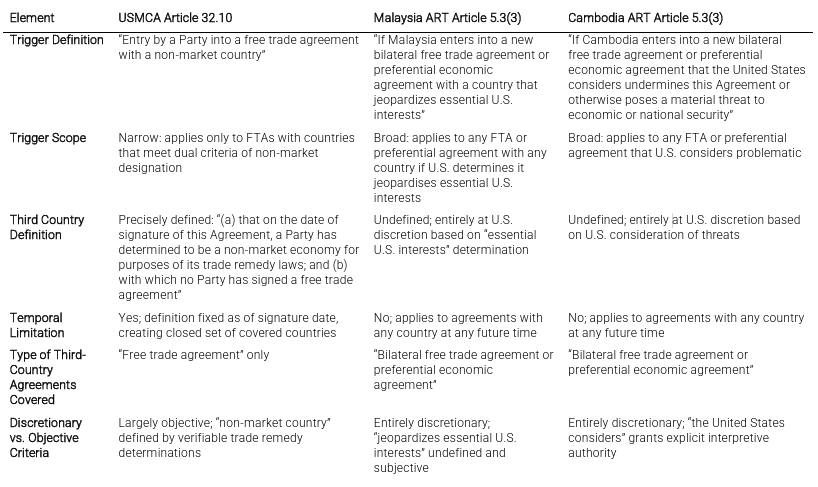

While sharing a common logic, the three provisions differ in trigger definitions, procedural safeguards, and remedial mechanisms. This briefing provides detailed comparative analysis of the poison pill provisions and assesses their implications for countries pursuing foreign economic policy strategies that seek to hedge between China and the United States.

The poison pill provisions included in the recently announced 2025 U.S.-Malaysia agreement differ from the USMCA precedent. These provisions amount to loyalty tests and should be seen in the context of intensifying U.S.-China competition for global influence.

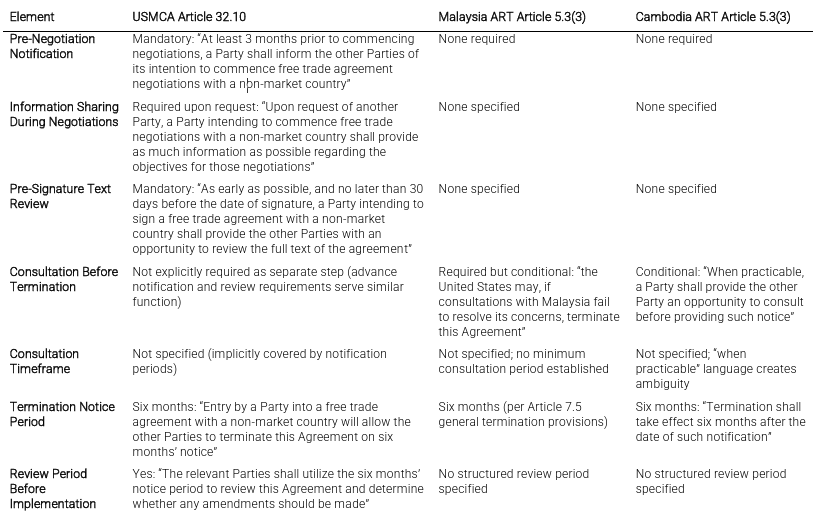

To the best of my knowledge, the USMCA was the first poison pill provision in U.S. trade policy in recent times. Article 32.10, titled “Non-Market Country FTA,” created a conditional termination mechanism triggered by any USMCA party objecting to another party entering into the negotiation of a free trade agreement with a “non-market country.” The provision includes detailed procedural safeguards: three months’ advance notice before commencing negotiations, text-sharing requirements, and a six-month termination notice period allowing remaining parties to translate that trilateral into a bilateral trade agreement.

The provision defines “non-market country” narrowly through two criteria: (a) a country designated as non-market for trade remedy purposes by at least one USMCA party, and (b) a country with which no USMCA party has signed a free trade agreement as of the USMCA signature date. On this definition, China is a non-market economy.

On October 26, 2025, ahead of the ASEAN Leaders Summit in Kuala Lumpur, the United States released full texts of trade agreements with Malaysia and Cambodia. These agreements employ broader third-country restriction language than the USMCA precedent, applying to any bilateral FTA or preferential economic agreement that “jeopardizes essential U.S. interests” (Malaysia) or “undermines this Agreement or otherwise poses a material threat to economic or national security” (Cambodia).

The Malaysia agreement explicitly links termination to Executive Order 14257 (April 2, 2025), which establishes reciprocal tariff frameworks. The Cambodia agreement references its own Article 7.4 termination provisions. Both agreements lack the extensive procedural safeguards present in USMCA Article 32.10, though both require consultations before termination.

On October 28, 2025—two days after the U.S.-Malaysia and U.S.-Cambodia agreements were released—China and ASEAN members signed the Protocol on Upgrading the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area to Version 3.0. Chinese Premier Li Qiang explicitly framed the upgrade as demonstrating “shared commitment…to firmly support multilateralism and free trade” in the face of “severe challenges to the rules-based international economic and trade system” and “unilateral tariff measures to provoke trade wars.”

The FTA 3.0 Upgrade Protocol expands inter-governmental cooperation into five new areas: digital economy, green economy, supply chain connectivity, competition and consumer protection, and support for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. This timing is notable. As of this writing, the agreed text of the Upgrade has not been released. Publication of that text will reveal if poison pills have been included there too.

The juxtaposition of U.S. agreements containing third-country restrictions and the China-ASEAN upgrade—announced within 48 hours—illustrates both competing initiatives advancing regional economic integration and the strategic choices ASEAN member states face.

These recent developments follow the announcement earlier this year of trade accords between the United States and the European Union, Indonesia, Japan, and the United Kingdom. None of those agreements included poison pills. (However, references to third-party practices can be found therein.) This raises the question: Why were poison pills included in some of this year’s U.S. trade deals and not in others? Before answering that question, it is appropriate to examine in depth the relevant provisions.

The three poison pill provisions in U.S. trade agreements share a common functional logic—influencing the future economic statecraft of partner countries. These three provisions differ along four dimensions: trigger definitions, procedural safeguards, remedial mechanisms, and approach to conditionality. In addition to the observations below, see the Tables at the end of this briefing for a structured comparison.

The USMCA provision employs a narrowly defined, procedural trigger mechanism. A "non-market country" must satisfy two criteria simultaneously: first, at least one USMCA party must have designated the country as a non-market economy for trade remedy purposes as of the agreement's signature date; and second, no USMCA party may have signed a free trade agreement with that country as of the signature date. This definition is temporally bounded, fixing the set of potential trigger countries at the moment of USMCA signature and thereby creating a closed, identifiable list of countries whose future FTAs with USMCA parties could activate the termination mechanism.

The Malaysia provision employs a substantively broad and discretionary trigger. The provision activates if Malaysia enters "a new bilateral free trade agreement or preferential economic agreement with a country that jeopardizes essential U.S. interests." Because the term "essential U.S. interests" remains undefined in the agreement text, the United States retains unilateral interpretive authority to determine which countries and which agreements pose such threats. Unlike the USMCA precedent, the provision contains no limitations that would restrict its application to agreements with specific countries or class of third countries. This means any future agreement with any country could potentially trigger U.S. termination rights if the United States determines it jeopardises U.S. interests.

The Cambodia provision similarly employs a broad trigger but incorporates dual substantive criteria. The provision applies to any agreement "that the United States considers undermines this Agreement or otherwise poses a material threat to economic or national security." The language puts U.S. judgement at the centre with the phrase "the United States considers," granting the United States interpretive authority while framing the trigger around two distinct concerns: economic undermining of the bilateral agreement itself and unspecified threats to U.S. economic or national security. Like the Malaysian provision, the Cambodian text contains neither definitional constraints specifying what constitutes "undermining" or "material threat" nor limitations identifying particular third countries of concern, leaving the provision applicable to any future agreement with any country that the United States judges problematic.

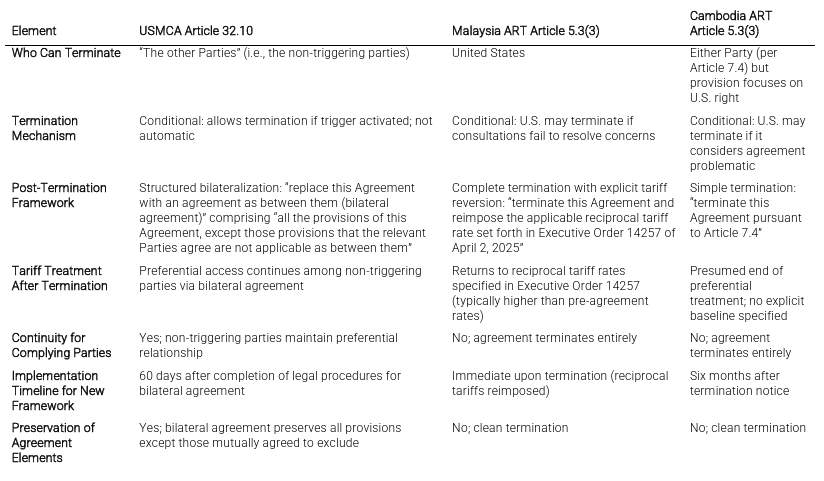

The USMCA establishes an extensive procedural architecture governing how the poison pill mechanism operates. At least three months before commencing free trade agreement negotiations with a non-market country, a USMCA party must inform the other parties of its intention to negotiate. Upon request from another party, the negotiating party must provide as much information as possible regarding the objectives for those negotiations. As early as possible, and no later than 30 days before signature, the party intending to sign an FTA with a non-market country must provide the other parties an opportunity to review the full text of the proposed agreement. If the trigger is activated, the non-triggering parties must provide six months' notice before terminating the trilateral agreement. During this six-month period, the remaining parties must review the agreement and determine whether any amendments should be made to the bilateral agreement that will replace the trilateral USMCA. This codified “bilateralisation” process allows the non-triggering parties to continue their preferential trading relationship with modifications whilst excluding the triggering party.

The Malaysia provision establishes minimal procedural requirements compared to the USMCA precedent. The provision mandates consultations with Malaysia if the United States determines that a proposed agreement jeopardises essential U.S. interests, but only if these consultations fail to resolve U.S. concerns may the United States proceed with termination. The agreement text does not specify consultation timeframes, establish minimum consultation periods, or create information-sharing requirements during Malaysia's negotiations with third countries. Beyond the consultation requirement embedded within the poison pill provision itself, the agreement does not establish notice periods or procedural steps beyond those contained in the general termination provisions found elsewhere in the agreement.

The Cambodia provision establishes an even more minimal procedural structure than the Malaysia agreement. The provision states simply that the United States "may terminate this Agreement pursuant to Article 7.4" if it considers a new agreement problematic. Article 7.4, which provides general termination procedures applicable to any termination of the agreement, specifies that either party may terminate with six months' written notice. Article 7.4 also states that "when practicable" the terminating party should provide the other party an opportunity to consult before providing termination notice. The conditional language "when practicable" creates ambiguity as to whether consultation obligations are mandatory or discretionary, and the provision establishes no requirements for advance notification before Cambodia commences third-country negotiations, information sharing during negotiations, or text review before signature.

Given its trilateral nature, the USMCA establishes a remedy designed to preserve trade rights and obligations between the remaining parties after the poison pill is triggered. Upon activation, the provision allows the non-triggering parties to terminate the trilateral agreement on six months' notice, but mandates that these parties replace the trilateral USMCA with a bilateral agreement between themselves. This bilateral agreement must be comprised of all USMCA provisions except those provisions that the relevant parties mutually agree are not applicable between them. The provision provides a six-month review period during which the parties shall utilise the termination notice period to review the agreement and determine whether any amendments should be made. The resulting bilateral agreement enters into force 60 days after completion of applicable legal procedures. This mechanism preserves maximum preferential market access amongst complying parties whilst excluding the triggering party, maintaining the benefits of trade liberalisation for countries that have not violated the poison pill provision.

The Malaysia provision establishes direct termination with explicit tariff reversion as the remedy. The United States may "terminate this Agreement and reimpose the applicable reciprocal tariff rate set forth in Executive Order 14257 of April 2, 2025." This explicit linkage to Executive Order 14257 establishes a clear baseline defining the post-termination tariff environment: termination returns both parties to the reciprocal tariff arrangements specified in the Executive Order, which in the case of Malaysia mean facing a 24% reciprocal tariff on exports to the United States. In principle, the Malaysia provision results in complete termination of the bilateral agreement, with both parties losing preferential access to each other's markets.

The Cambodia provision establishes simple termination via general provisions without specifying post-termination tariff arrangements. The United States may "terminate this Agreement pursuant to Article 7.4," which provides that termination takes effect six months after written notification. Unlike the Malaysia agreement, the Cambodia text does not explicitly reference tariff baselines, reciprocal tariff frameworks, or Executive Order 14257, leaving the post-termination tariff environment ambiguous in the text itself. Termination would presumably end the preferential tariff treatment established under the agreement, returning the parties to whatever tariff regime would apply in the absence of the bilateral agreement, but the provision does not specify whether this means reversion to MFN rates, WTO-bound rates, pre-agreement applied rates, or rates established through subsequent U.S. policy measures, such as Executive Orders.

The three provisions involve distinct approaches to conditionality, although the more recent provisions are arguably more similar than the earlier precedent.

The USMCA provision establishes ex ante criteria defining trigger countries through objective, verifiable determinations (non-market economy designations for trade remedy purposes). The provision creates extensive procedural requirements governing notification, information sharing, and text review before any termination can occur. The remedy is structured to preserve cooperation amongst complying parties through mandatory bilateralisation. This architecture prioritises predictability: parties can identify in advance which countries are covered, understand the procedures that will govern any activation, and know that complying parties will maintain preferential access even if one party triggers the provision. The trigger's narrow definition limits uncertainty regarding which future agreements could activate termination rights, as the set of non-market countries is fixed at the agreement's signature date.

The Malaysia provision grants broad U.S. discretion in trigger determination through the undefined term "jeopardizes essential U.S. interests," allowing the United States to determine unilaterally which third-country agreements pose problems. However, the provision clearly specifies the remedy through explicit reference to Executive Order 14257's reciprocal tariff levels.

This architecture combines flexibility in application with some certainty in consequences: whilst Malaysia cannot predict with confidence which future agreements might trigger U.S. concerns, it knows precisely what tariff regime will apply if termination occurs. The explicit Executive Order linkage may serve as a deterrent by clearly establishing the economic consequences of non-compliance, making the alternative to maintaining the agreement concrete and calculable rather than ambiguous.

The Cambodia provision grants the United States maximum flexibility in both trigger determination and implementation, with minimal procedural constraints on either. The phrase "the United States considers" explicitly centres U.S. judgement regarding what "undermines this Agreement or otherwise poses a material threat to economic or national security." The provision establishes no advance notification requirements, no mandatory information sharing, and only conditional consultation obligations through the ambiguous "when practicable" language. The remedy is simple termination without explicit specification of post-termination tariff arrangements. This architecture prioritises U.S. policy latitude over predictability, granting maximum discretion in every respect.

Assessing the strategic significance of poison pill provisions requires examining their likely purpose, the leverage they create for the United States, and the constraints they effectively impose on the economic statecraft of partner countries.

Several possible U.S. motivations could be relevant.

1. Strategic Competition and Sphere-of-Influence Considerations

The provisions function as what might be termed economic alignment mechanisms in great power competition. By creating explicit costs for partner countries that deepen economic integration with strategic competitors—such as China—the United States seeks to construct a network of trading partners with explicit incentives to discourage dual economic engagement.

The evolution from USMCA’s narrow “non-market country” definition to the 2025 agreements’ expansive “essential U.S. interests” language reflects a shift toward more comprehensive alignment efforts. The USMCA provision, negotiated in 2018, employed relatively legalistic criteria that required objective determination. The 2025 provisions abandon these constraints in favour of unilateral U.S. discretion, suggesting increased U.S. determination to leverage market access as geopolitical rivalry intensifies.

The timing of the China-ASEAN FTA 3.0 upgrade underscores the competitive trade policy dynamics underway. By securing agreements with Cambodia and Malaysia containing third-country restrictions immediately before a major ASEAN summit where China announced a substantially upgraded FTA, was the United States attempting to constrain certain ASEAN members’ ability to fully leverage the upgraded China-ASEAN trade pact?

Ultimately, poison pill provisions transform trade agreements from purely commercial instruments into tools for managing partner countries’ broader foreign economic policy orientation.

2. Preserving Preferential Market Access Through Exclusivity

If the United States provides tariff concessions to Malaysia and Cambodia, and those countries subsequently grant similar or superior market access to a strategic competitor, this erodes the net gains of the United States. In principle, poison pills can protect preferential market access granted to the United States if Malaysia or Cambodia decline third party overtures for negotiations towards a regional trade agreement.

The provisions address a longstanding feature of reciprocal non-multilateral trade agreements: without exclusivity mechanisms, preferential access loses value as partners extend similar or better treatment to third countries. Traditional rules of origin prevent simple transshipment but cannot prevent more sophisticated preference erosion. Poison pills afford some protection for preferential market access.

3. Bilateral Investment Accords In Scope

The formal statement of the Cambodian and Malaysia poison pills does not confine their scope to free trade agreements of concern to the United States. In principle, bilateral accords between these countries and third parties that facilitate or liberalise cross-border investment are in scope.

Consider Chinese firms considering the establishment of manufacturing operations in Cambodia or Malaysia. If those operations met extant rules of origin—using sufficient local or U.S. content—the goods would likely qualify for better U.S. market access terms when compared to exporting directly from China. The commercial benefit of such manufacturing operations flows largely to Chinese companies, an outcome the United States may find unattractive or objectionable. Poison pill provisions that frustrate signature of new bilateral investment treaties and other forms of investment cooperation limit the degree to which Cambodia and Malaysia will be further integrated into cross-border supply chains with America’s strategic competitors.

Looking across these three potential rationales, poison pills effectively outsource certain economic security functions to partner governments. Rather than the United States monitoring and responding to every problematic third-country practice affecting bilateral trade, the provisions create incentives for partner governments themselves to limit economic integration with countries whose practices the United States considers problematic. This distributes enforcement costs across multiple countries while preserving U.S. authority to define what practices warrant concern.

Several forms of leverage are created by these provisions and their effectiveness is likely to vary.

1. Direct Market Access and Alternative Export Destinations

Cambodia sends 42% of its merchandise exports to the United States (according to the latest WTO Trade Profiles). Termination threats carry with them significant economic consequences given Cambodia’s heavy U.S. market dependence. For Malaysia, which sends 11.5% of goods exports to the United States, matters are different. Overall American leverage is more modest. However, Malaysian electronics, semiconductors, and certain manufactured goods depend on U.S. market access, implying that sector-specific leverage can prove significant.

Another factor conditioning U.S. leverage created by poison pills is the availability of alternative export markets. Countries highly dependent on U.S. market access in sectors where China does not provide comparable import demand face more acute American leverage. Put differently, countries with diversified export markets or where China provides significant alternative demand[1] face less American leverage. A related factor is the relative growth rate of bilateral exports to the United States and other destinations—as it conditions how quickly any lost export sales to the United States can be replaced.

2. Investment Decisions and Supply Chain Configuration

Beyond trade flows, the provisions affect investment decisions by multinational firms and supply chain configuration choices. A foreign investor considering production facilities in Malaysia or Cambodia must evaluate not only current tariff rates but the probability of termination and resulting tariff reversion under various scenarios.

This uncertainty may affect investment in two ways:

Risk Premium Effect: Investors may demand higher returns to compensate for termination risk, reducing investment flows into affected countries or increasing the cost of capital for projects dependent on U.S. market access.

Diversification Effect: Firms may structure supply chains to avoid dependencies on countries facing poison pill constraints, either by establishing parallel capacity in multiple locations or by avoiding countries whose third-country FTA negotiations create U.S. termination risk.

The provisions thereby extend U.S. influence beyond direct government-to-government relationships to affect private-sector strategic planning. This secondary leverage may exceed direct trade-flow leverage for some countries, particularly those seeking to position themselves as regional manufacturing hubs.

3. Leverage in Partner Countries’ Future Negotiations with Third Parties

The poison pill provisions create asymmetric negotiating dynamics for partner countries in future trade negotiations with third countries. When Malaysia or Cambodia negotiate trade agreements, they must consider potential U.S. reactions even absent explicit U.S. participation in those negotiations.

This grants the United States informal influence over partner countries’ trade policy without formal consultation requirements. Partner countries face several strategic choices:

Advance Consultation: Partner countries may informally consult with the United States before commencing third-country negotiations to gauge if U.S. concerns might trigger poison pill provisions. This transforms bilateral agreements into instruments of broader trade policy coordination.

Negotiating Constraints: Partner countries may limit what they offer third countries in trade negotiations to avoid triggering U.S. concerns, effectively granting the United States veto power over certain aspects of partner countries’ trade policy.

Sequential Negotiations: Partner countries may prioritize U.S. agreements over other potential agreements, or time negotiations strategically to avoid simultaneous pursuit of agreements that might trigger U.S. concerns.

The leverage mechanism operates through uncertainty about U.S. reactions. Because terms like “jeopardizes essential U.S. interests” (Malaysia) and “undermines this Agreement or otherwise poses a material threat” (Cambodia) are undefined, partner countries must guess what would trigger U.S. termination. This ambiguity may prove more constraining than precise definitions would be, as partner countries may err toward excessive caution to avoid termination risk.

4. Demonstration Effects and Precedent-Setting

The inclusion of poison pill provisions in the Malaysia and Cambodia agreements creates precedent that may affect U.S. negotiations with other countries. If poison pills become standard U.S. practice, countries negotiating future U.S. agreements face increased pressure to accept similar provisions.

This leverage mechanism operates through expectation-setting rather than direct coercion. Once poison pills appear in multiple agreements, countries may accept them as non-negotiable elements of U.S. trade policy rather than as provisions subject to negotiation. The progression from USMCA (one provision) to Malaysia and Cambodia (two provisions with broader language) to potentially additional agreements creates momentum toward normalizing poison pills as standard trade agreement architecture.

The demonstration effect extends beyond countries directly negotiating with the United States. Third countries observing U.S. poison pill provisions may adjust their own trade policy expectations, either by limiting what they seek from potential FTA partners subject to U.S. poison pills or by reconsidering their own approach to third-country restrictions in trade agreements.

5. Constraints on U.S. Leverage

The following five factors constrain U.S. leverage from poison pill provisions in trade agreements:

Lost U.S. Exports: If the United States terminates agreements with Malaysia or Cambodia, U.S. exporters lose preferential access to those markets. While asymmetry generally favours the United States given relative market sizes, termination imposes costs on U.S. commercial interests. Agricultural exporters, semiconductor equipment manufacturers, and other sectors that benefit from preferential access face material losses from agreement termination.

Small Tariff Snapback: As provided for in its recent agreement with Malaysia, should the United States terminate that accord then the reciprocal tariff rate faced by Malaysian firms exporting to the United States will rise from 19% to 24%. While a five percent increase in tariffs across-the-board would until recently have been considered a significant setback, given contemporary trade policy dynamics, such a change may no longer be seen as that much of a commercial disadvantage. Should that view take root in Malaysia then it weakens any threat of agreement termination by the United States.

Alternative Market Access Through Regional Frameworks: China-ASEAN FTA 3.0, RCEP, and other regional frameworks provide alternative preferential access for partner countries. Countries may calculate that sacrificing U.S. preferential access is an acceptable cost for maintaining deeper Asian regional integration. The poison pill provisions may prove less binding than they appear if partner countries possess viable alternatives.

No Precedent of Use: To date, no poison pill provision has been invoked, creating uncertainty about whether they represent a genuine constraint or merely symbolic (and provocative) language.

Collective Action by U.S. Trading Partners: Deliberate ASEAN defiance of poison pill constraints—for example, through collective pursuit of upgraded China-ASEAN FTA terms—could reduce U.S. leverage by making termination threats less credible. This consideration is pertinent if the United States is unlikely to terminate agreements with multiple countries simultaneously.

In sum, the existence of a poison pill clause alone does not create significant leverage for the United States. Other factors condition the leverage created. The relevance of these factors should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Whether this condition is met is determined, in part, by the openness of Chinese trade policy.

The Malaysia and Cambodia precedents establish several implications for countries engaged in or contemplating trade negotiations with the United States:

1. Inclusion of Poison Pill Provisions Should Be Expected

From now on, U.S. trading partners should anticipate that U.S. negotiators demand the inclusion of poison pills. Foreign governments may face pressure to accept provisions modelled on Malaysia/Cambodia templates rather than USMCA’s more circumscribed model. The evolution from narrow to broad definitions, and from extensive to minimal procedural safeguards, suggests U.S. negotiating positions have hardened rather than softened over time.

Absent the cessation and resolution of geopolitical rivalry, which is not a central scenario, then the question for negotiating partners is not whether such provisions will appear but what form they will take and what procedural safeguards can be secured. Therefore, trading partners should prepare position papers on poison pills during preparation for ensuing negotiations.

2. Inclusion of Poison Pills and Associated Procedural Safeguards Are Negotiable.

That some trade deals signed by the United States this year do not include poison pills suggests that the matter is negotiable. Countries with greater negotiating leverage—whether due to market size, geopolitical significance, strategic location, or U.S. interest in concluding agreements—may be able to resist inclusion of such poison pills. As a fallback position, such trading partners may be able to obtain stronger procedural protections should poison pills be included.

However, the trend from USMCA to Malaysia/Cambodia suggests procedural safeguards will be harder to secure for smaller and medium-sized trading partners. Foreign negotiators may want to prioritise procedural protections explicitly rather than assuming they will be offered voluntarily.

3. Poison Pills Should Be Seen As Part of A Broader Focus on Economic Security

Trading partners that seek trade deals with the United States—perhaps to negotiate down their so-called reciprocal tariff—should expect demands to align on Economic Security matters. Poison pills are just one element. Both the Malaysia and Cambodia agreements contain multiple Economic Security provisions beyond the poison pill:

Alignment with U.S. sanctions and export controls

Measures against third-country firms’ unfair practices

Investment screening cooperation

Technology transfer prohibitions

Therefore, trading partners seeking agreements with the United States must evaluate whether their broader foreign economic policy can accommodate substantial alignment requirements along these lines, not just whether they can accept isolated poison pill provisions.

This integration of Economic Security matters into trade agreements represents a further shift away from traditional trade liberalisation.

4. Engagement with Strategic Competitors of the United States

One purpose of these poison pills is to encourage America’s trading partners to re-evaluate their engagement with China. Thailand and Vietnam’s ongoing negotiations with the United States occur against the backdrop of their existing China-ASEAN FTA participation and RCEP membership. The poison pill provisions force these countries to evaluate whether the terms on offer for preferential access to the United States compensate for any constraints on deepening China-ASEAN ties.

While dual engagement with China and the United States is not proscribed, poison pill provisions create explicit tensions that make comprehensive dual engagement more difficult. In short, governments may need to revise their hedging strategies.

5. Regional Group Cohesion Faces New Pressures

The bilateral U.S. approach—negotiating separately with individual ASEAN members rather than with ASEAN collectively—combined with poison pill provisions that potentially constrain ASEAN-level agreements with third countries, raises questions about ASEAN cohesion.

ASEAN members face a choice about whether to coordinate their U.S. negotiations collectively (potentially strengthening negotiating leverage but complicating individual countries’ bilateral relationships) or to negotiate individually (potentially securing country-specific advantages but fragmenting ASEAN cohesion and negotiating power).

The evidence to date suggests that the United States has little to worry about ASEAN cohesion, but that may change. Similar matters may arise in other regions, such as in the European Union and Gulf Council states.

6. Implementation Creates Ongoing Uncertainty

The poison pills’ expected impact depends on their ultimate implementation, which remains uncertain. No poison pill provision has been invoked to date, creating ambiguity about the circumstances that would actually trigger termination and whether the United States would carry out termination threats. Indeed, some in the United States may regard this uncertainty as a form of beneficial Strategic Ambiguity.

Foreign governments negotiating new U.S. agreements will have to decide whether it is wise to seek greater clarity about implementation triggers and consequences (potentially reducing ambiguity but also reducing flexibility) or instead to accept ambiguity in exchange for other negotiating priorities.

This sequence of recent developments described here illustrates the extent to which trade talks have been explicitly integrated into great power competition. The poison pill provisions serve as mechanisms for translating U.S. market access into alignment with American strategic interests, inducing partner countries to make increasingly explicit choices about economic orientation in a fragmenting global trade system. Hedging strategies by America’s trading partners may have become harder to sustain.

That said, there are compelling grounds to doubt whether—as currently negotiated by the United States—poison pills are quite the “nuclear option” that some might fear. Yes, the language of termination is stark. But post-termination trading terms may not change that much. Put differently, a key determinant of the teeth of these provisions is whether the treatment of a trading partner’s commercial interests by the United States changes markedly after agreement termination.

As currently structured, in the case of Malaysia, termination would result in the general reciprocal tariff rate rising from 19% to 24%. In the past, a 5% increase in tariff rate would have been seen as disastrous. Given the events of this year, such a change may be seen, by the end of 2025, as bad but not exceptional. And, of course, to the extent that any termination is just a pretext for another negotiation and deal with the United States, then the trading partner may discount the likelihood of a permanent termination of better preferential access to the United States market.

Of course, such considerations imply that the United States will have to decide whether to couple termination with (a) a massive increase in the reciprocal tariff rate for the trading partner in question[2], (b) statements that termination will not be followed by any subsequent negotiation and (c) removal of other non-commercial benefits enjoyed by the trading partner, possibly in the national security and broader foreign policy domains. In short, the United States has options too. Whether American officials are prepared to use them is another matter.

These concluding observations reinforce the finding that the likely effect of poison pills is contingent on many factors. One goal of this briefing was to identify those factors so that officials, corporate executives with responsibilities for geopolitics and political risk, as well as analysts can assess in the round the overall threat in particular circumstances posed by poison pills in trade agreements.

The effectiveness of poison pills in shaping—even deterring—hedging strategies between China and the United States will vary depending on each country's specific circumstances—their export dependence and sectoral vulnerabilities, alternative market access, negotiating leverage, and expected post-termination tariff treatment.

For some trading partners, these poison pill provisions may bite; for others, they are a manageable obstacle as they execute their foreign economic policies in this era of intensifying geopolitical rivalry. However, foreign governments should bear in mind that both Beijing and Washington, DC have at their disposal additional tools to intensify pressure on trading partners in the months and years ahead.

This is on the assumption that extant reciprocal tariffs are ruled legal by the U.S. Supreme Court, another source of uncertainty going forward.

Simon J. Evenett is Founder of the St. Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade, Professor of Geopolitics and Strategy at IMD Business School, and Co-Chair of the World Economic Forum’s Trade & Investment Council.

Article 32.10.1 (Definition): For the purposes of this Article: non-market country is a country: (a) that on the date of signature of this Agreement, a Party has determined to be a non-market economy for purposes of its trade remedy laws; and (b) with which no Party has signed a free trade agreement.

Article 32.10.2 (Pre-Negotiation Notification): At least 3 months prior to commencing negotiations, a Party shall inform the other Parties of its intention to commence free trade agreement negotiations with a non-market country.

Article 32.10.3 (Information Sharing): Upon request of another Party, a Party intending to commence free trade negotiations with a non-market country shall provide as much information as possible regarding the objectives for those negotiations.

Article 32.10.4 (Text Review): As early as possible, and no later than 30 days before the date of signature, a Party intending to sign a free trade agreement with a non-market country shall provide the other Parties with an opportunity to review the full text of the agreement.

Article 32.10.5 (Termination Right): Entry by a Party into a free trade agreement with a non-market country will allow the other Parties to terminate this Agreement on six months’ notice and replace this Agreement with an agreement as between them (bilateral agreement).

Article 32.10.6 (Bilateral Agreement Content): The bilateral agreement shall be comprised of all the provisions of this Agreement, except those provisions that the relevant Parties agree are not applicable as between them.

Article 32.10.7 (Review Period): The relevant Parties shall utilize the six months’ notice period to review this Agreement and determine whether any amendments should be made.

Article 32.10.8 (Entry into Force): The bilateral agreement enters into force 60 days after completion of applicable legal procedures.

If Malaysia enters into a new bilateral free trade agreement or preferential economic agreement with a country that jeopardizes essential U.S. interests, the United States may, if consultations with Malaysia fail to resolve its concerns, terminate this Agreement and reimpose the applicable reciprocal tariff rate set forth in Executive Order 14257 of April 2, 2025.

If Cambodia enters into a new bilateral free trade agreement or preferential economic agreement that the United States considers undermines this Agreement or otherwise poses a material threat to economic or national security, the United States may terminate this Agreement pursuant to Article 7.4.

[Note: Article 7.4 provides general termination procedures: “Either Party may terminate this Agreement by providing written notice of termination to the other Party. Termination shall take effect six months after the date of such notification. When practicable, a Party shall provide the other Party an opportunity to consult before providing such notice.”]