Rerouted Supply, Uneven Absorption: Firm-Level Transmission of Trade Wars

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #83

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #83

Concerns about the re-routing of Chinese exports to third markets have been a recurring feature of trade policy debates since 2018—first through fears of trade diversion following U.S. Section 232 measures, and later through the 2018–2019 U.S. tariff rounds on China. The underlying narrative is familiar: when access to the U.S. market is restricted, Chinese exporters are expected to redirect supply toward other economies. This redirection is widely perceived as a threat, as it may intensify import competition, depress domestic prices and undermine local producers.

On 26 January, I read an insightful Financial Times article—“UK sofa retailer emerges as unlikely winner from Trump’s trade war”—which highlighted a less explored dimension of the re-routing debate. The key insight is that re-routing increases supply pressure in receiving markets, but its effects differ sharply across firms.

For import-competing domestic producers, re-routed Chinese supply is typically harmful. Lower-priced imports reduce achievable selling prices, compress margins, erode volumes and can raise shutdown risks—especially in sectors with high fixed costs or close product substitutability. By contrast, import-intensive firms, such as retailers sourcing from diverted Chinese supply, may benefit. Greater supply can improve sourcing conditions through discounts, rebates or more favourable payment terms.

Whether these cost reductions are passed on to consumers depends on competition and product characteristics. In highly commoditised, easy-to-ship goods, stronger competition tends to translate into lower retail prices. For bulky, high-value, or experiential goods—such as furniture—competition is less purely price-based, allowing retailers to retain a larger share of the cost savings as margins.

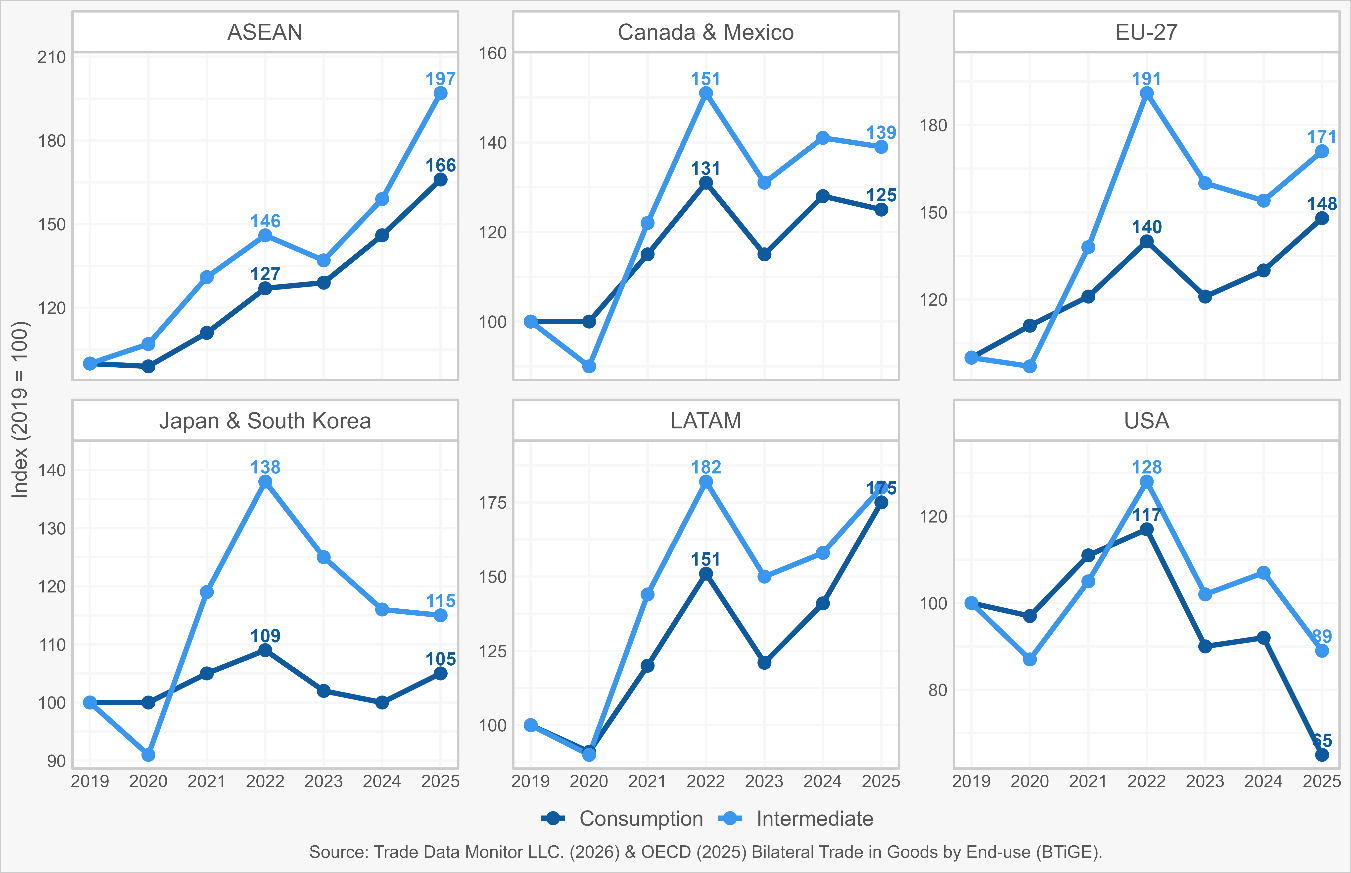

This observation motivates the empirical exercise in this piece. I examine how imports from China have grown across major economies by distinguishing between intermediate and final consumption goods. Specifically, I analyse imports from China into the United States; Canada and Mexico; the EU-27; Japan and South Korea; selected ASEAN economies (Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore); and selected Latin American economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru) over the period 2019–2025.

The analysis uses Trade Data Monitor data on imports from China from January to November of each calendar year, ensuring comparability across countries given incomplete December data for 2025. Products are classified using OECD end-use definitions. Intermediate goods are inputs fully consumed in the production of other goods and services, while consumption goods are purchased for direct final use and not used in further production.

Figure 1 indexes imports from China to 2019 = 100 within each region and end-use category. In the United States, the EU-27, Canada and Mexico, and Japan and South Korea, imports of consumption goods initially increased faster than intermediate imports in 2020–2021. From 2021 onward, however, intermediate imports generally grew more strongly. Most regions experienced their largest deviations from 2019 levels in 2022, with one notable exception: ASEAN economies. In ASEAN, intermediate imports from China in 2025 are 97% higher than in 2019, while consumption imports are 66% higher. The United States stands out as the only area where both intermediate and consumption imports from China are lower in 2025 than in 2019. Latin America shows large increases in both categories, particularly for consumption goods.

Figure 1 provides a first indication of where post-2019 import growth from China has been concentrated. In most regions, growth has been stronger in intermediate inputs than in final consumption goods. This suggests that adjustment pressures associated with re-routing have tended to operate more through firms’ production chains than through retail markets.

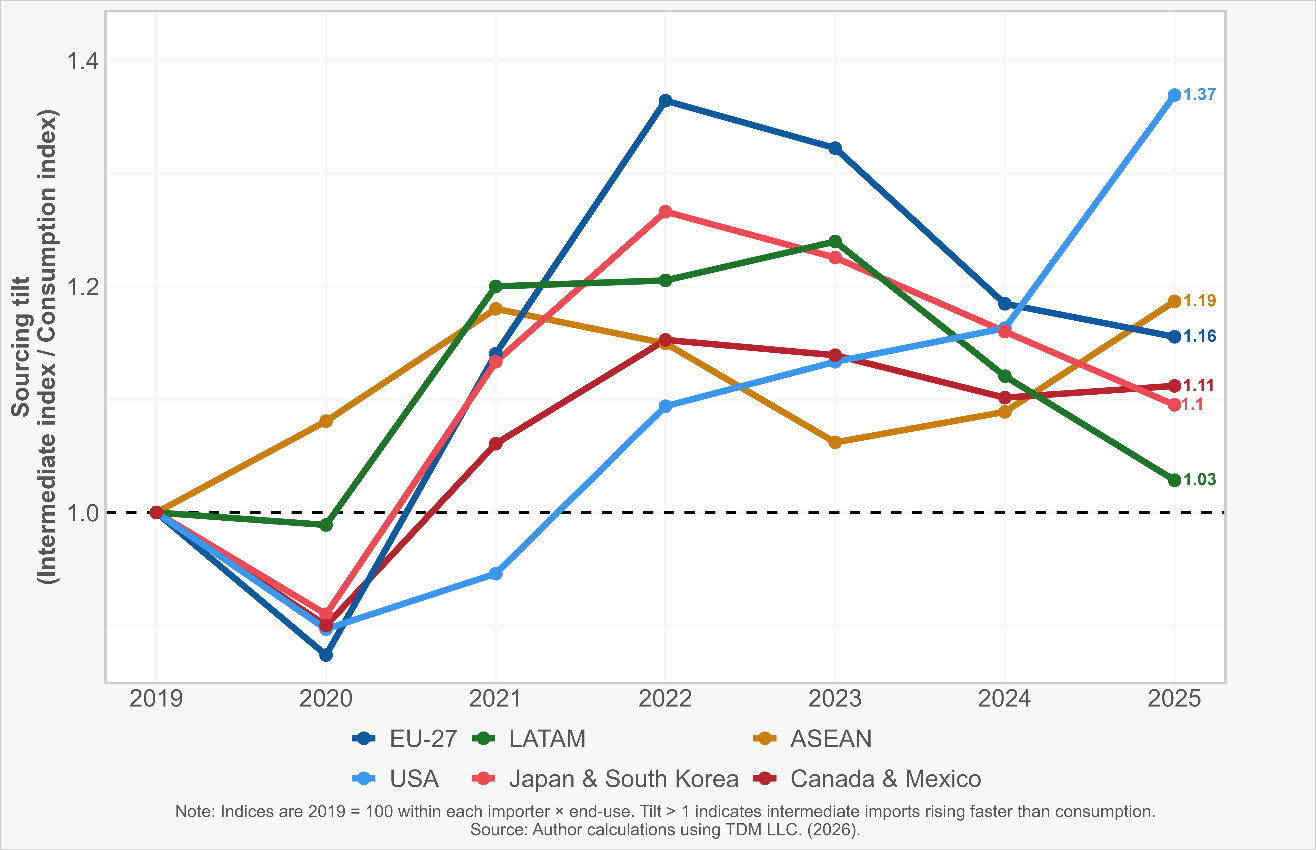

Figure 2 summarises this pattern using a single diagnostic indicator: the Sourcing versus Consumption Tilt, defined as the ratio of the intermediate import index to the consumption import index. A tilt above one indicates that, since 2019, intermediate imports from China have grown faster than consumption imports; a tilt below one indicates the opposite.

In 2020, consumption imports retained their relative importance across most regions, with ASEAN as the exception, where intermediate imports rose sharply. From 2022 onward, several regions—including the EU-27, ASEAN, and Latin America—exhibit a clear upward shift in the tilt. Over most of the period, the tilt remains above one in all regions, indicating that post-2019 import growth from China has been relatively more input-intensive than consumption-intensive.

Developments in 2025 reveal notable regional differences. The U.S. tilt remains closer to unity or rises later, consistent with stronger trade barriers and slower growth in imports of Chinese consumption goods. Canada and Mexico, as well as ASEAN economies, show a renewed increase in the relative growth of intermediate imports. By contrast, the EU-27 tilt moves closer to one, signalling a relative strengthening of consumption import growth. A similar—and even stronger—pattern is observed in Japan and South Korea and in Latin America.

In these regions, post-2019 import growth increasingly shifts toward consumption goods. In theory, this rebalancing implies stronger potential retail price pressure relative to earlier years, though the extent of pass-through depends on competition and market structure.

This end-use perspective highlights underexplored channels through which import re-routing can affect domestic economies. It reveals substantial cross-country differences in whether post-2019 import growth from China has been relatively more input- or consumption-intensive. As re-routing becomes a structural feature of geopolitical competition, understanding these transmission channels is increasingly important for assessing industrial viability and price dynamics.

Fernando Martín is Associate Director at Global Trade Alert, leading the Analytics team, and Geopolitical Strategist at IMD