Industrial Policy as Market-Shaping Competition

Evidence from China, the European Union, and the United States (2009–2024)

Evidence from China, the European Union, and the United States (2009–2024)

Industrial policy has returned, but in a form that differs markedly from earlier episodes of state intervention. What began in the aftermath of the global financial crisis as selective support for economic recovery has, since 2020, become increasingly intertwined with concerns over resilience, security, and geopolitical rivalry. Governments are no longer primarily focused on correcting isolated market failures or smoothing cyclical adjustment. Instead, they are actively reshaping market structure—altering relative competitive conditions across firms and borders through subsidies, localisation requirements, procurement preferences, and restrictions on imports, exports, and investment. For firms operating across jurisdictions, industrial policy is therefore no longer background context; it has become a central determinant of competitive advantage, market access, and strategic risk.

This paper documents how industrial policy has evolved across the three major geopolitical and economic blocs—China, the European Union, and the United States—using an extended version of the New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) dataset constructed from Global Trade Alert (GTA). The resulting panel spans 2009–2024 and is uniquely suited to analysing industrial policy as a competition-shaping phenomenon. GTA coding focuses on concrete state actions that plausibly alter relative treatment and competitive conditions, rather than on broad macroeconomic or horizontal policies. Exploiting this feature, the paper derives ten stylised facts that characterise the scale, structure, and dynamics of contemporary industrial policy across the Big Three.

The stylised facts reveal a distinctive configuration of modern industrial policy. First, selective industrial actions have increased sharply and remain persistently high, indicating a shift from episodic intervention toward a high-intervention regime. Second, policy design has evolved: while subsidies dominate across all three jurisdictions, instrument choice diverges sharply, and trade-restricting measures increasingly complement financial support. Third, stated policy motives have been reoriented away from competitiveness and efficiency toward security, resilience, and geopolitical considerations. Fourth, industrial actions have become increasingly concentrated in strategic sectors and chokepoints within global value chains, particularly in dual-use technologies and upstream inputs. Fifth, industrial policy operates in an explicitly international and interactive environment: subsidies propagate rapidly across jurisdictions, are frequently followed by defensive trade measures, and are increasingly directed at rival economies rather than applied diffusely. Finally, policy instruments differ systematically in persistence, with export restrictions becoming structurally durable while import restrictions remain more contingent. Together, these features point to a form of industrial policy that is persistent, strategic, and rival-directed, rather than temporary, sector-neutral, or purely domestic.

Throughout the paper, the unit of analysis is an industrial action: a concrete, codified state measure—such as a subsidy award, regulatory restriction, or trade barrier—that plausibly alters relative competitive conditions across firms or borders, as identified by GTA/NIPO coding rules. Focusing on industrial actions allows the analysis to capture how policy instruments are deployed, combined, and sustained over time, and how they interact across jurisdictions in ways that matter for competition and trade.

From the perspective of the multilateral trading system, this evolution raises fundamental governance questions. Many of the instruments documented in this paper—selective subsidies, localisation requirements, import restrictions, export controls, and trade-defence measures—operate at the margins of existing WTO disciplines or rely on established flexibilities, including subsidy exemptions, contingent protection, and security exceptions (Hufbauer & Jung, 2023; Rubini, 2024). As a result, industrial policy increasingly shapes trade outcomes not through negotiated tariff commitments, but through instruments that are difficult to discipline ex ante and costly to contest ex post. By documenting how these measures scale, persist, and interact across jurisdictions, the stylised facts presented here provide systematic empirical evidence on the growing strain placed on the rules-based trading system by the return of state-centred competition.

The contribution of the paper is twofold. Substantively, it offers an integrated empirical account of contemporary industrial policy across China, the European Union, and the United States, linking policy instruments, stated motives, sectoral targeting, international sequencing, directional focus, and policy persistence within a single analytical framework. Methodologically, it exploits the rich structure of the extended NIPO panel—organised by implementing jurisdiction, affected jurisdiction, product, instrument, time, and motive—to move beyond documenting the scale of industrial policy and toward analysing its strategic patterning: how state actions cluster across sectors, how they propagate internationally, and how long they remain in force. These patterns are directly relevant for policymakers concerned with governance, transparency, and restraint, and for firms operating in an environment in which state actions increasingly shape the terms of competition across markets.

The contemporary resurgence of industrial policy has generated a rapidly expanding literature across economics, political economy, and international trade. Early debates were dominated by scepticism grounded in concerns over information failures, rent-seeking, and government capture (Pack & Saggi, 2006). More recent work, however, has moved toward a more nuanced assessment, emphasising heterogeneity in outcomes, the importance of policy design, and the institutional conditions under which selective state intervention may shape market structure and firm behaviour. At the same time, a parallel literature has documented that modern industrial policy differs qualitatively from earlier episodes: it is larger in scale, more persistent, increasingly multi-instrument, and more tightly entangled with trade policy, security objectives, and geopolitical rivalry. This paper contributes to that literature by documenting systematic empirical patterns in the evolution, composition, and interaction of industrial policy actions across China, the European Union, and the United States since 2009.

A central insight of the recent literature is that industrial policy should be understood not simply as episodic support to particular firms or sectors, but as a set of state actions that reshape competitive conditions, investment incentives, and market access over time. Synthesising micro-empirical evidence, Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik (2024) argue that industrial policy can affect entry, innovation, and export performance when it targets identifiable coordination or learning externalities and is embedded in capable institutions. At the same time, they stress that effects are highly context dependent and sensitive to instrument choice and governance. Similarly, Warwick (2013) and Warwick and Nolan (2014) emphasise that modern industrial policy increasingly operates through complex policy mixes—including finance, regulation, procurement, and trade instruments—rather than through narrow subsidy programmes alone, complicating both evaluation and discipline.

This shift in perspective has encouraged greater attention to how industrial policy is implemented rather than whether it exists. Mazzucato and Rodrik (2023) develop a taxonomy of conditionalities embedded in industrial policy instruments, highlighting how eligibility rules, localisation requirements, and performance criteria shape firm behaviour and competitive outcomes. From a trade perspective, these design features matter because they often alter relative treatment between domestic and foreign firms even when policies are not formally framed as trade measures. This insight motivates empirical approaches—such as the New Industrial Policy Observatory—that focus on discrete policy actions plausibly affecting competitive conditions rather than on aggregate spending alone (Evenett et al., 2024).

A defining feature of recent industrial policy is its concentration in sectors deemed strategically salient. Semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, clean technologies, and critical raw materials occupy central positions in this literature. Goldberg, Juhász, and Lane (2024) characterise semiconductors as a canonical case in which learning, scale economies, and security externalities intersect, while also emphasising that international spillovers and technology diffusion complicate purely national strategies. Similarly, work on renewable energy and electric vehicles shows that early movers—most notably China—combined sustained industrial support with trade exposure, generating rapid cost reductions alongside international competitive pressures (Nahm, 2017; Pegels & Lütkenhorst, 2014; Reguant, 2024).

The growing emphasis on strategic sectors is closely linked to a broader shift in stated policy motives. While earlier interventions were often justified by competitiveness or employment objectives, recent industrial policies increasingly invoke resilience, security of supply, and national security. Farrell and Newman (2019) conceptualise this shift as “weaponised interdependence,” in which states exploit chokepoints in global networks to exert leverage. Empirical work on export controls illustrates how these instruments operate differently from tariffs, with effects mediated through global value chains and firm networks rather than through border prices alone (Hayakawa et al., 2023; Deseatnicov, 2024). These insights suggest that industrial policy has become a tool not only for promoting domestic capacity but also for managing strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities.

A growing body of evidence highlights that industrial policy operates in an interactive international environment. Subsidies and other support measures generate cross-border spillovers by altering trade flows, investment patterns, and competitive positions abroad. Using product-level data, Rotunno and Ruta (2024) show that subsidy interventions are associated with changes in imports and exports of targeted products, consistent with business-stealing effects. Firm-level evidence further suggests that foreign industrial policies induce adjustment through offshoring, reallocation along value chains, and changes in sourcing strategies (Cen et al., 2024).

Recent work also points to increasingly rapid policy sequencing across jurisdictions. Evenett et al. (2025) document that major subsidy announcements are frequently followed by similar interventions elsewhere, raising concerns about subsidy races and escalation. Choi and Levchenko (2021) provide historical evidence that industrial policy can have long-lived effects on firm growth and sectoral structure, reinforcing the importance of understanding persistence and feedback dynamics. Together, these studies motivate closer empirical attention to the timing, direction, and interaction of industrial policy actions across countries—an emphasis central to the stylised facts developed in this paper.

The expansion of industrial policy has intensified debates over transparency and trade governance. Standard WTO notification systems capture only a subset of contemporary support measures, particularly where assistance is delivered through financial intermediaries, tax expenditures, or regulatory conditionality (OECD, 2019; OECD, 2023). As a result, monitoring initiatives such as the New Industrial Policy Observatory play a complementary role by documenting discrete policy actions and enabling cross-country comparison (Evenett et al., 2024).

Legal and policy scholarship has begun to assess the implications of this shift for the multilateral trading system. Hufbauer and Jung (2023) and Rubini (2024) argue that existing subsidy disciplines struggle to accommodate large-scale, multi-purpose programmes such as the Inflation Reduction Act, while Fang (2025) highlights tensions between green industrial policy and WTO rules. Hoekman and Nelson (2025) emphasise that many contemporary interventions pursue non-economic objectives—climate, security, resilience—making cooperation both more necessary and more complex. A common theme across this work is that industrial policy increasingly shapes trade outcomes through instruments that are difficult to discipline ex ante and costly to contest ex post.

This paper builds on and contributes to these literatures by providing a systematic empirical characterisation of contemporary industrial policy across the three largest economic blocs. Rather than evaluating the causal impact of individual programmes, it documents stylised facts on the scale, persistence, motives, sectoral concentration, sequencing, and durability of industrial actions that plausibly alter competitive conditions. By focusing on concrete policy actions—subsidies, trade restrictions, and related instruments—the analysis connects firm- and sector-level industrial policy debates to trade-relevant outcomes and governance concerns. In doing so, it complements existing micro-empirical and legal scholarship with a descriptive foundation that clarifies how industrial policy has evolved from episodic intervention to a persistent, strategic, and internationally interactive feature of the global economy.

The empirical analysis draws on the New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) and its historical extension (H-NIPO), both derived from the Global Trade Alert (GTA) database of unilateral commercial policy interventions. GTA has systematically tracked policy changes affecting trade and investment worldwide since 2009. NIPO is an IMF–GTA monitoring initiative that records “new industrial policy” measures from 1 January 2023 onwards and is updated monthly, with broad country coverage (Evenett et al., 2024). H-NIPO extends the same conceptual framework back to 2009, providing a large-scale historical baseline for analysing the evolution of industrial policy over time (Evenett et al., 2025).

This paper uses an extended NIPO panel that combines H-NIPO data for the period 2009–2023 with subsequent NIPO vintages through December 2024. The resulting dataset allows consistent comparison of industrial policy activity across China, the European Union, and the United States over a fifteen-year horizon encompassing the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the subsequent period of heightened geopolitical tension.

A central advantage of NIPO for the purposes of this paper is that the database is explicitly designed to capture policy interventions that plausibly alter relative competitive conditions across firms and borders. GTA applies a set of coding rules—including the Relative Treatment Test and a Meaningful Change criterion—to identify interventions that change the treatment of foreign versus domestic commercial interests in relevant markets. As a result, the dataset systematically emphasises policy actions with direct competitive implications, such as selective subsidies, localisation and procurement preferences, and restrictions on imports, exports, or investment, while excluding broad macroeconomic or horizontal measures.

Accordingly, the unit of observation is not industrial policy announcements or strategic rhetoric, but concrete state interventions that plausibly reshape the competitive environment faced by firms. This focus makes the dataset particularly suitable for analysing industrial policy as a market-shaping phenomenon rather than as a collection of isolated fiscal or regulatory initiatives.

NIPO and H-NIPO identify industrial policy interventions through two complementary inclusion routes. First, NIPO includes measures when official policy documents explicitly cite motives such as national security, geopolitical concern, security of supply, strategic competitiveness, or the climate and low-carbon transition (Evenett et al., 2024). For the historical period, H-NIPO backfills motive classifications for 2009–2022 using a RoBERTa language model trained on the 2023 NIPO sample to infer stated rationales from policy texts (Evenett et al., 2025).

Second, measures are included if they affect predefined lists of strategic products and services, irrespective of whether explicit motives are stated. These lists cover low-carbon technologies, dual-use goods, critical minerals, semiconductors, medical products, and selected digital services, identified at the HS-6 and CPC-3 levels. A measure enters the dataset if it satisfies at least one of these criteria. In addition, NIPO records industrial strategies and plans even before they translate into firm-level actions, reflecting their potential to shape expectations, investment decisions, and subsequent policy sequencing.

Each observation in the dataset corresponds to a distinct state intervention, such as a subsidy programme, regulatory restriction, procurement rule, localisation requirement, or trade measure. For the stylised facts presented in this paper, the data are organised as a panel at the implementing jurisdiction, affected jurisdiction, HS-6 product, policy instrument and month-year level.

Key variables include the implementing and affected jurisdictions; announcement, implementation, and removal dates; a detailed instrument taxonomy covering subsidies, export incentives, import and export restrictions, trade defence measures, foreign investment measures, procurement, and localisation policies; stated motives; strategic sector and technology classifications; and, where available, subsidy values from 2020 onward. This structure allows the analysis to trace not only the scale of industrial policy activity, but also its sectoral focus, directional targeting, sequencing across jurisdictions, and persistence over time.

The original NIPO contribution documents the distribution of industrial policy instruments and stated motives in 2023 and provides early evidence of strategic interaction across jurisdictions (Evenett et al., 2024). The H-NIPO extension establishes a long-run baseline and identifies a marked intensification of industrial policy activity after 2020 (Evenett et al., 2025).

This paper builds on that foundation by using the extended panel to integrate scale, instrument choice, motive reorientation, sectoral concentration, cross-jurisdictional sequencing, directional targeting, and policy persistence within a single empirical framework. By focusing on the Big Three economies, the analysis highlights how industrial policy increasingly operates as a competitive and interactive system, and how these dynamics translate into changing patterns of exposure for firms operating within and across major economic blocs.

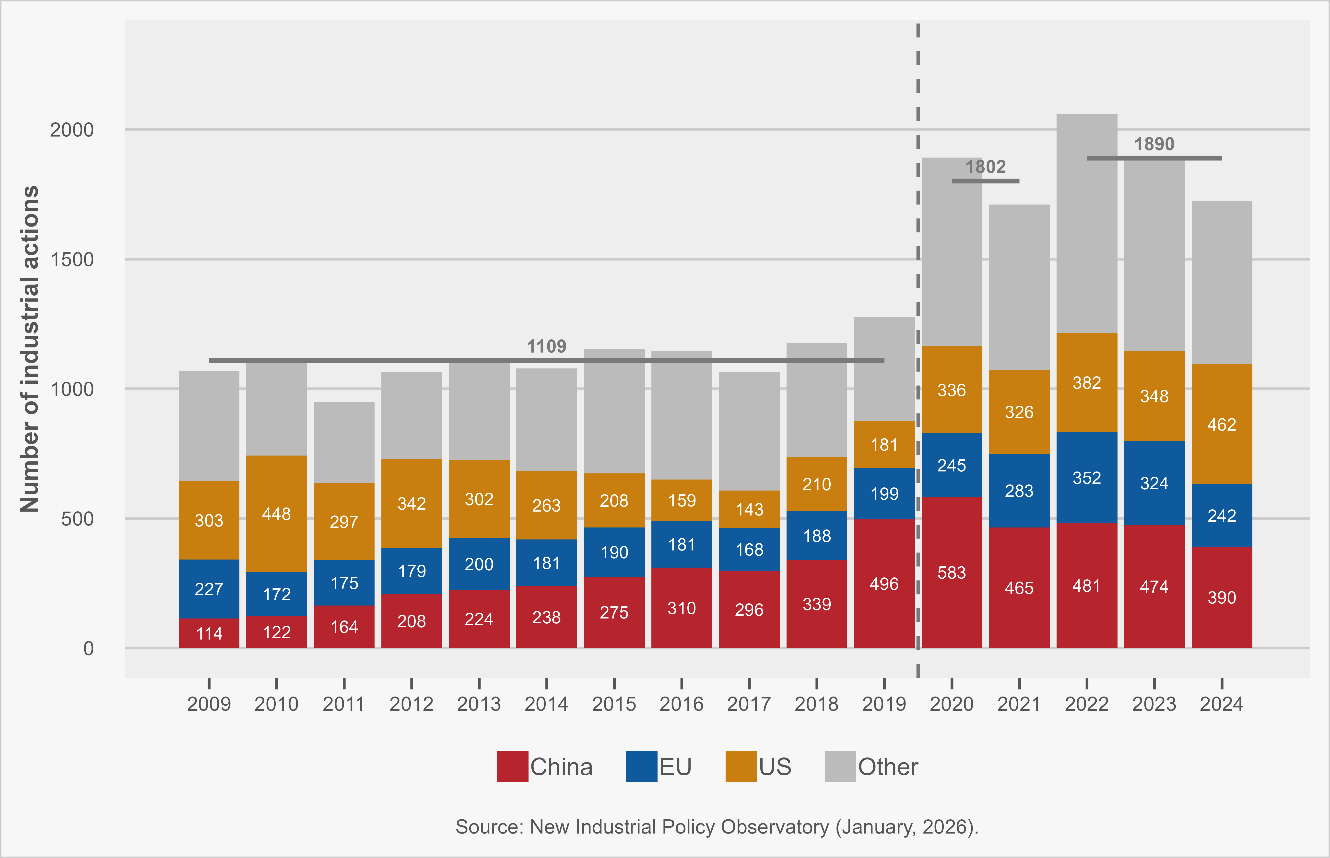

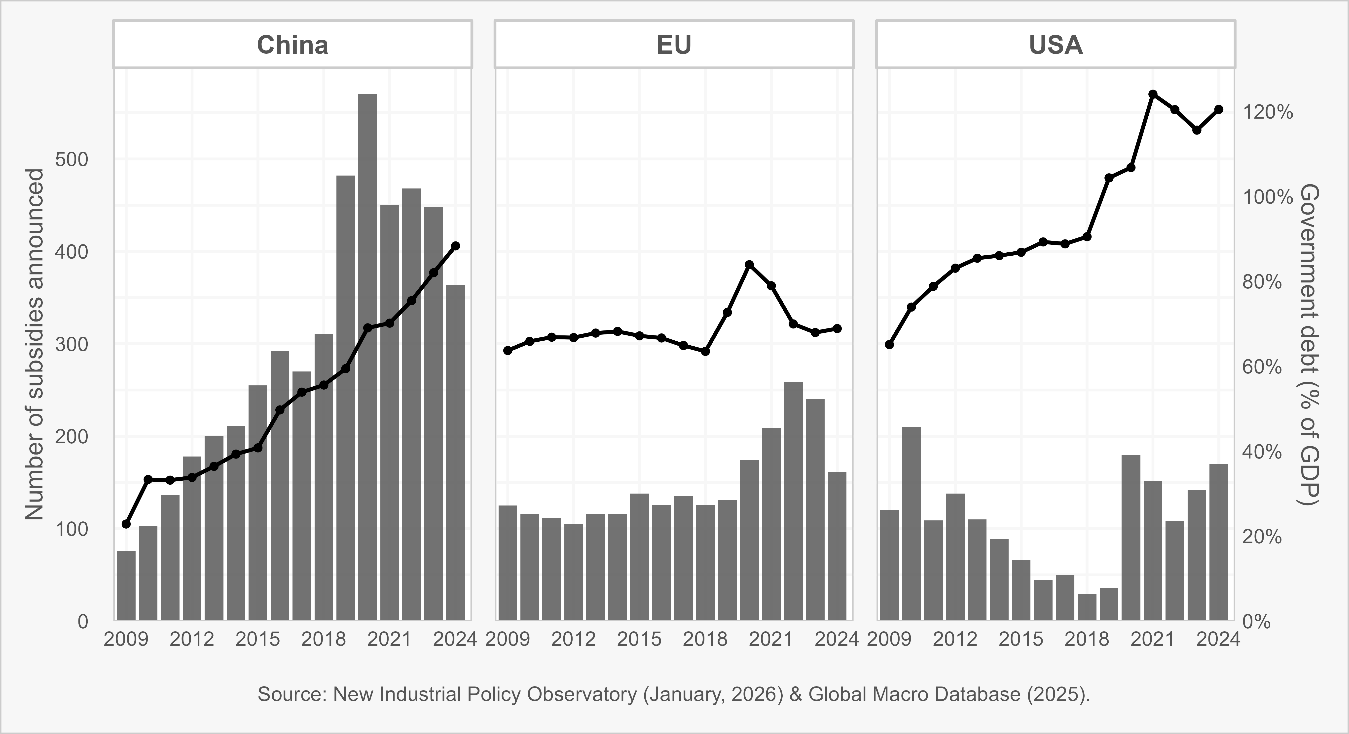

The global use of selective, competition-distorting industrial policy rises sharply after 2019 and remains persistently high through 2024, indicating a structural shift in state intervention rather than a temporary, crisis-driven deviation.

Figure 1 reports industrial actions that alter relative treatment between domestic and foreign firms through discriminatory subsidies, localisation or procurement requirements, and restrictions on market access. All measures satisfy the Relative Treatment Test and the Meaningful Change criterion, ensuring that recorded actions plausibly affect competitive conditions and international commercial flows. The figure therefore captures a narrow but economically consequential subset of industrial policy: concrete state actions that explicitly disadvantage foreign commercial interests and reshape market conditions.

Three distinct phases emerge. Between 2009 and 2019, the annual number of selective industrial actions remains broadly stable, fluctuating around an average of approximately 1,100 measures per year. Although episodic increases occur, there is no sustained upward trend during this period. This pattern is consistent with an environment in which industrial policy was present but more often channelled through horizontal or broadly applicable instruments—such as general financial support, regulatory adjustments, or macroeconomic stabilisation—that are less likely to meet discrimination-based inclusion criteria and less systematically concentrated in sectors later defined as strategic within the NIPO framework.

A clear break occurs after 2019. In 2020–2021, the annual number of selective industrial actions rises abruptly to around 1,800. Activity increases further in 2022–2024, with yearly totals approaching 1,900 measures. The horizontal mean lines in Figure 1 confirm that this represents a discrete upward shift in the level of selective state intervention rather than a transitory spike. Unlike earlier surges observed in the early 2010s, the post-2019 increase does not unwind: action counts remain consistently above pre-2019 levels through the end of the sample. This persistence mirrors recent findings that industrial policy activity has remained elevated even as acute crisis conditions recede (Evenett et al., 2024; Evenett et al., 2025).

The timing of this acceleration points to successive shocks as triggering events. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in medical supplies, logistics, and semiconductors; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine intensified concerns over energy security and strategic dependence; and the escalation of US–China technological rivalry reframed industrial policy as an instrument of geopolitical competition. However, the sustained high level of interventions suggests that shocks alone cannot account for the observed pattern. Crisis conditions appear to have lowered political and institutional barriers to selective state action, after which measures were retained, expanded, and embedded into standing policy frameworks—consistent with arguments that contemporary industrial policy increasingly operates as a durable governance regime rather than an emergency response (Hoekman & Nelson, 2025; Juhász, Lane & Rodrik, 2024).

Importantly, the post-2019 expansion is broad-based rather than jurisdiction-specific. China’s use of selective industrial policy rises sharply around 2020 and remains high thereafter. The United States records a pronounced increase aligned with large, explicitly targeted programmes such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, which combine financial support with domestic-content conditions and eligibility rules that systematically disadvantage foreign producers. The European Union, following a period of more moderate activity in the mid-2010s, also exhibits a marked post-2020 increase, reflecting pandemic-era relaxations of state-aid rules and their partial institutionalisation under the Green Deal Industrial Plan.

These patterns point toward a regime in which industrial policy increasingly shapes market structure on a durable basis. Rather than correcting isolated market failures or responding temporarily to shocks, governments appear to be using selective instruments to manage exposure to foreign competition, reallocate rents along strategic value chains, and insulate domestic producers from external pressures. For firms and policymakers alike, the relevant question is therefore no longer whether industrial policy will recede, but how its expanding footprint will reshape competitive conditions and international trade relations over the medium term.

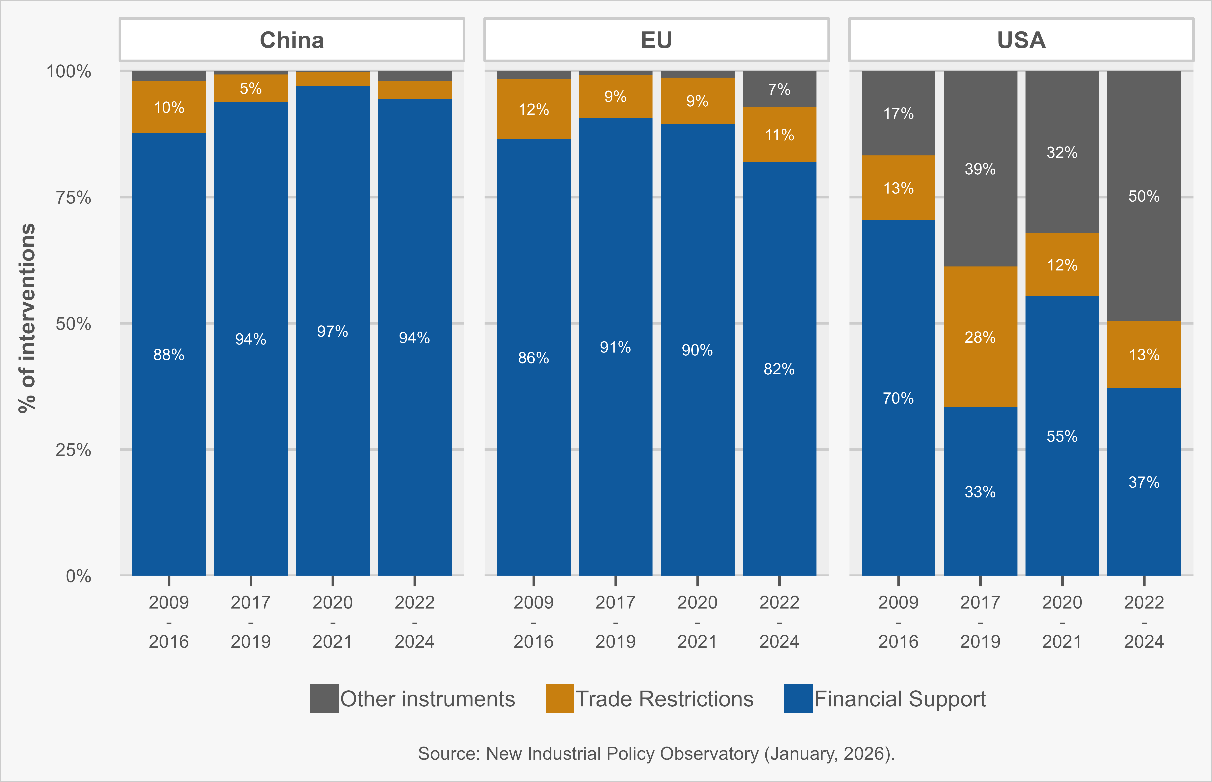

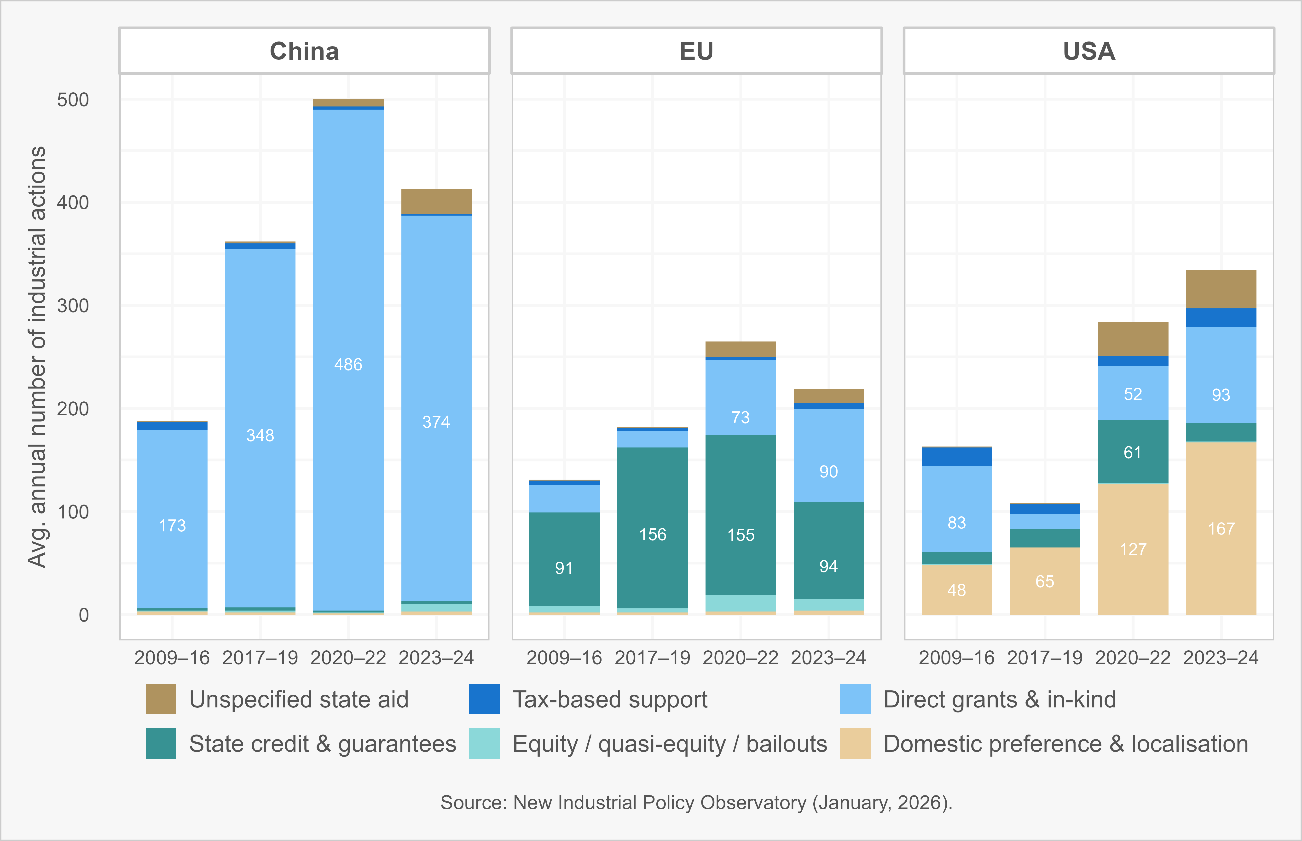

Financial support instruments dominate industrial policy across China, the European Union, and the United States over 2009–2024. However, the composition, delivery, and governance of these instruments differ systematically, with the United States relying on a structurally more heterogeneous and trade-exposed policy mix than either China or the European Union.

Across all three economies, Figure 2 shows that domestic subsidies and export incentives account for the majority of recorded industrial actions throughout the sample period. In China and the European Union, financial support consistently represents between roughly 85 and 97 percent of all industrial actions in every sub-period. This dominance is stable over time and persists through the post-2019 expansion documented in Stylised Fact 1, indicating that the recent surge in activity reflects an intensification of existing policy instruments rather than a wholesale shift away from subsidies.

The United States exhibits a distinct pattern. While financial support remains a central component of US industrial policy, trade restrictions and other non-subsidy instruments account for a substantially larger share of industrial actions in every period. This divergence is already visible in the late 2010s—prior to the sharp post-2020 acceleration—and persists thereafter. As a result, the US industrial policy toolkit is consistently more diversified than that of China or the European Union, combining subsidies with border measures, regulatory constraints, and eligibility-based instruments that directly condition access to the domestic market.

In China, financial support accounts for close to—or above—90 percent of all industrial actions throughout the sample. This pattern reflects the central role of direct fiscal transfers, in-kind assistance, and policy-directed finance within China’s development strategy, where industrial policy is closely integrated with state-controlled banking and investment systems. A substantial literature documents how this framework blurs the boundary between explicit subsidies and state-mediated credit allocation, using both to expand capacity, accelerate technological upgrading, and support domestic champions (Naughton, 2021; WTO, 2023; Rhodium Group, 2024). From a trade perspective, this institutional structure makes the scale and incidence of support difficult to observe ex ante, while allowing industrial policy to operate persistently through financial channels rather than through overt border measures.

The European Union displays a different configuration. Figure 2 shows a gradual increase in non-subsidy instruments after 2017 and a visible rise in “other instruments” during 2022–2024, but financial support remains overwhelmingly dominant. This pattern is consistent with the EU’s institutional approach, which channels industrial policy primarily through state-aid–compatible mechanisms—grants, credit guarantees, and concessional loans—rather than through explicit trade restrictions. Successive crisis frameworks, notably during the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy-price shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, temporarily relaxed state-aid constraints and expanded the permissible scope of support while preserving formal adherence to EU competition rules (European Commission, 2020, 2022; Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2024). The result is an activist but legally mediated industrial policy regime in which subsidies scale up without a commensurate rise in overt border instruments.

By contrast, US industrial policy systematically combines subsidies with trade- and regulation-based instruments. As Figure 2 shows, import restrictions, trade defence measures, and regulatory conditionalities account for a larger and more persistent share of US industrial actions than in China or the EU. This reflects a long-standing tradition in which industrial policy is embedded within a broader policy toolkit that includes trade remedies, procurement rules, and regulatory eligibility conditions, rather than being delivered primarily through fiscal transfers alone (Irwin, 2020; Evenett & Fritz, 2023). Recent flagship programmes—the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act—exemplify this approach, coupling large-scale financial support with domestic-content requirements, localisation incentives, and eligibility rules that systematically disadvantage foreign producers.

Figure 3 further shows that the apparent dominance of financial support masks substantial cross-country differences in delivery mechanisms. In China, financial support is overwhelmingly composed of direct grants and in-kind assistance, accounting for roughly 93–97 percent of subsidy measures. The European Union relies more heavily on mediated finance—credit, guarantees, and loans—particularly prior to 2020, reflecting both its fiscal architecture and the constraints imposed by state-aid rules. The United States, by contrast, combines grants and tax credits with regulatory and eligibility conditions, embedding subsidies within governance structures that tie support to production location, sourcing decisions, and compliance with policy objectives, especially after 2020.

These patterns point to persistent divergence in industrial policy regimes rather than convergence toward a single model. While all three economies rely heavily on subsidies, they embed them within distinct institutional and legal frameworks that shape how firms access support, the conditions attached to it, and the interaction between industrial policy, trade policy, and competition rules. For firms, these differences translate into heterogeneous compliance costs, localisation incentives, and exposure to policy risk across jurisdictions. For policymakers, they imply that the global resurgence of industrial policy is producing not a uniform subsidy race, but a set of interacting regimes whose design differences are likely to shape patterns of retaliation, coordination, and fragmentation in the years ahead.

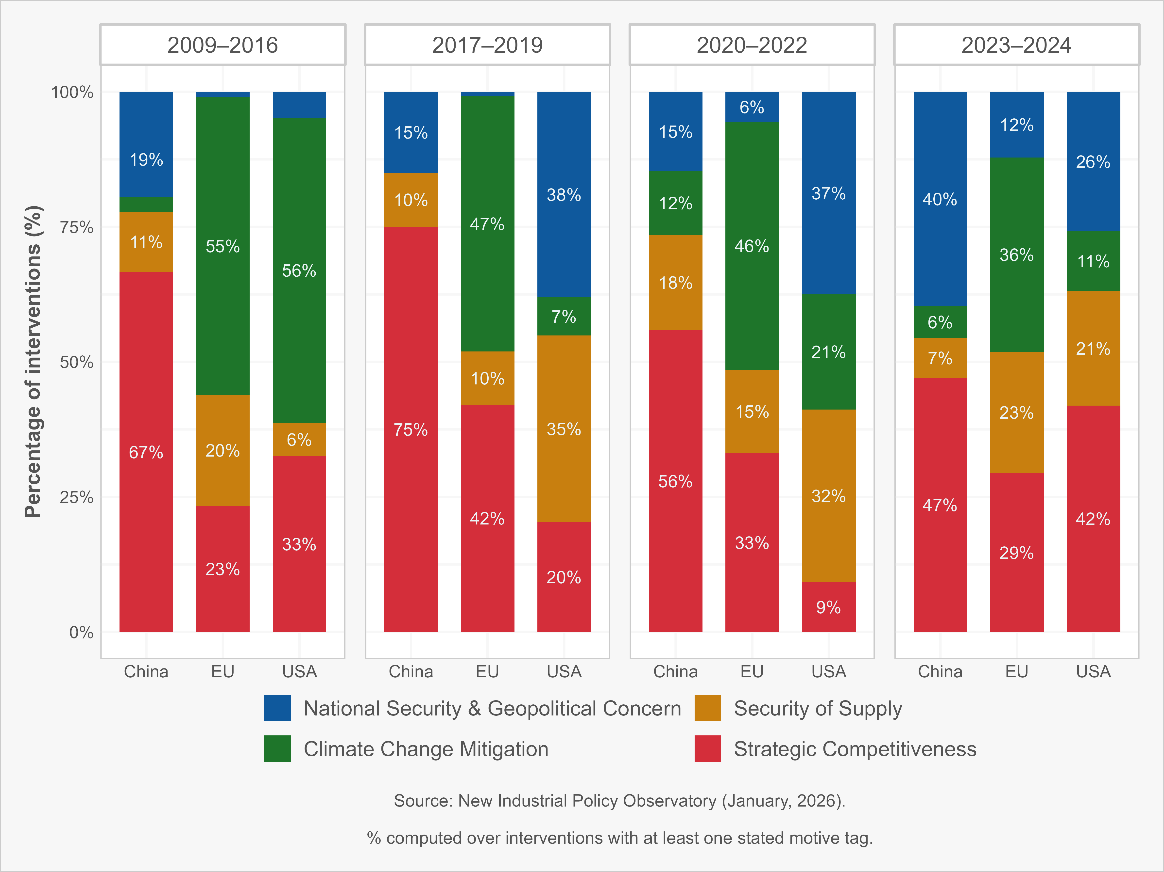

Since 2020, the stated rationales underlying industrial actions shift away from competitiveness and climate mitigation toward security, resilience, and geopolitical concerns across China, the European Union, and the United States.

Figure 4 traces the evolution of stated policy motives for industrial actions across the three jurisdictions, restricting attention to measures that explicitly report at least one rationale. Motives are grouped into four categories: strategic competitiveness, climate change mitigation, security of supply, and national security or geopolitical concern. Percentages are calculated over motive-tagged actions, allowing comparison of the relative emphasis of different objectives across time and jurisdictions rather than changes in absolute policy activity.

In the early period (2009–2016), industrial policy is predominantly framed in terms of strategic competitiveness. In China, approximately two-thirds of motive-tagged actions cite competitiveness-related objectives, consistent with policies aimed at industrial upgrading, export performance, and technological catch-up. In the United States, competitiveness also dominates, although national security and geopolitical concerns already account for a non-trivial share of stated motives. In the European Union, stated rationales are more diversified, with climate mitigation playing a visible role alongside competitiveness even in this early period.

Between 2017 and 2019, climate change mitigation emerges as the dominant framing in the European Union, accounting for close to half of motive-tagged actions. This shift coincides with the consolidation of EU climate and energy policy, including renewable-energy support schemes and the early articulation of the European Green Deal. During the same period, climate-related motives remain comparatively limited in the United States, while China continues to emphasise competitiveness, supplemented by a gradual increase in security-of-supply concerns.

After 2020, the composition of stated motives changes sharply across all three jurisdictions. National security and geopolitical considerations rise substantially, most prominently in the United States. In 2020–2022, more than one-third of US motive-tagged actions cite security or geopolitical objectives, with this share increasing further in 2023–2024. Over the same period, the relative importance of competitiveness declines, and climate-related motives remain secondary. The European Union follows a similar but more gradual trajectory. Climate mitigation remains prominent through 2020–2022 but subsequently declines, as security-of-supply and geopolitical resilience gain importance—particularly in relation to critical raw materials, energy inputs, and strategic technologies. China exhibits a distinct pattern: competitiveness remains the dominant framing throughout, but security-related motives rise steadily after 2020, reflecting increasing emphasis on technological self-reliance and domestic circulation.

Figure 4 therefore documents a broad reframing of industrial policy away from market-failure correction and environmental externalities toward security-oriented rationales. In the United States, this shift is abrupt and pronounced, aligning with the escalation of US–China technological rivalry and with policies explicitly justified by concerns over strategic dependence, chokepoints, and dual-use technologies. In the European Union, the transition is more incremental, reflecting the layering of security and resilience objectives onto an existing climate-centred policy framework rather than a wholesale replacement. China’s trajectory combines continuity and change: competitiveness remains central, but security narratives increasingly complement it as part of a broader strategy of technological self-sufficiency.

Importantly, the divergence across jurisdictions indicates that the global turn toward security-motivated industrial policy does not produce a single, uniform narrative. Instead, similar shocks—including the COVID-19 pandemic, energy disruptions, and geopolitical fragmentation—are interpreted and operationalised through distinct institutional and strategic lenses. This finding is consistent with political-economy accounts that emphasise how states mobilise security rationales differently depending on institutional structure and strategic position within global value chains (Farrell & Newman, 2019; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

This reframing has material implications for the dynamics of industrial policy. Security-based justifications tend to be less time-bound, less easily reversible, and more resistant to international coordination or dispute settlement than competitiveness- or climate-based rationales. As a result, the shift in stated motives documented here is likely to reinforce the persistence and accumulation of industrial policy actions identified in Stylised Fact 1, while deepening cross-country asymmetries in policy design, strategic intent, and exposure to retaliatory dynamics.

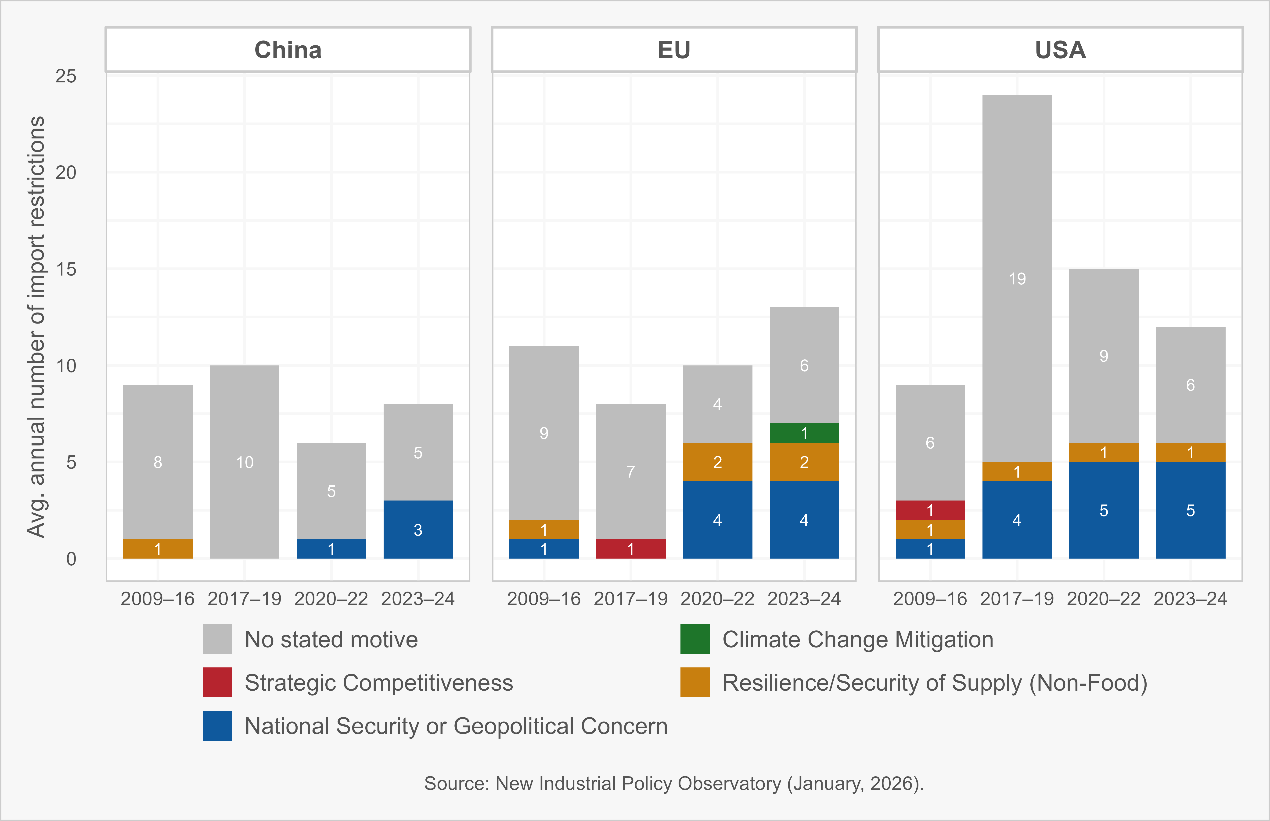

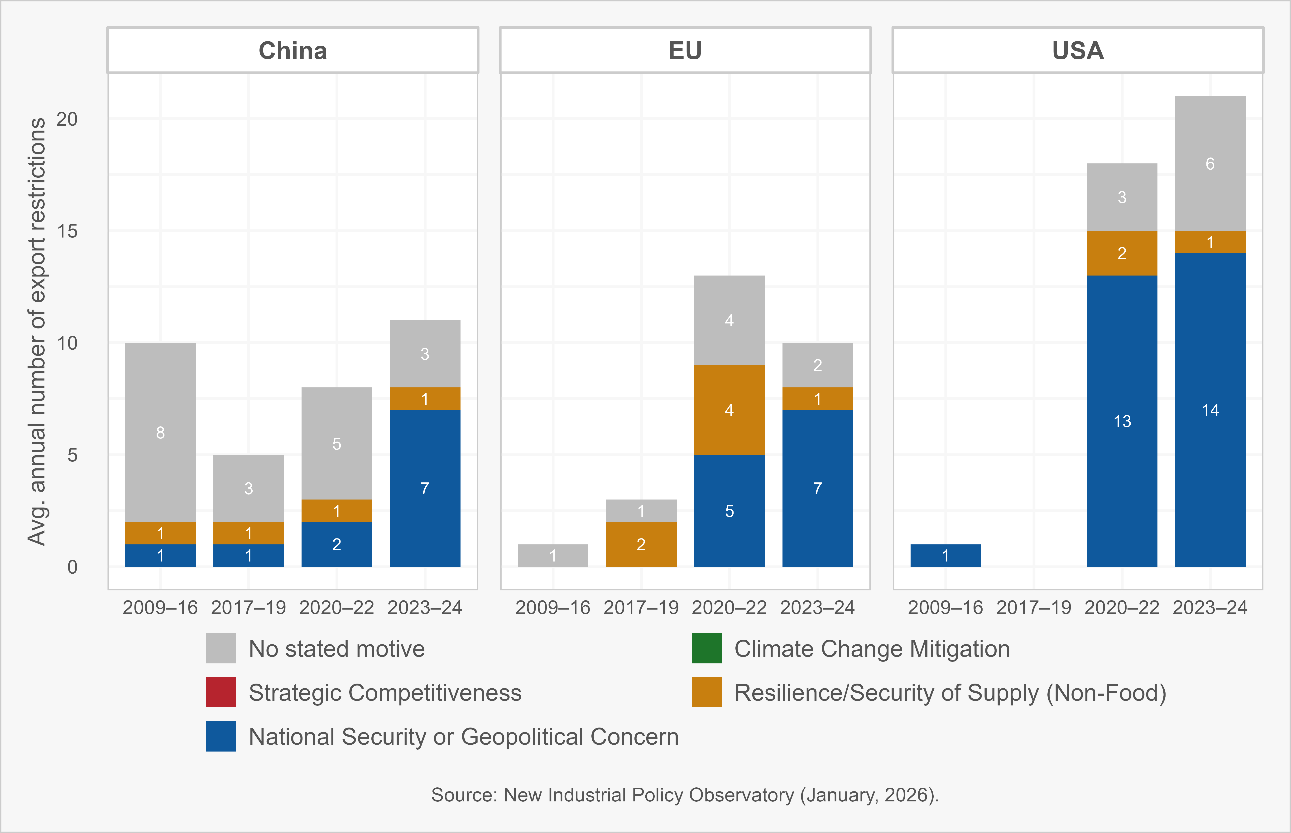

Import and export restrictions are far more likely than subsidies to be justified by national security, geopolitical, and security-of-supply motives, particularly after 2020. This pattern is most pronounced in the United States, but is also evident in the European Union and, with a lag, in China.

Figures 5 and 6 report the average annual number of import- and export-restricting industrial actions across China, the European Union, and the United States, disaggregated by stated policy motive and grouped into four sub-periods. As in Stylised Fact 3, the figures distinguish between industrial actions with explicit motive tags and those without stated rationales. Percentages and levels are interpreted jointly to characterise how different instruments are justified when governments articulate their objectives.

Two broad patterns emerge. First, although a non-trivial share of trade restrictions—especially prior to 2020—lack explicitly stated motives, the composition of motive-tagged trade restrictions differs sharply from that observed for subsidies. Across all three economies, when motives are stated, import and export restrictions are disproportionately associated with national security, geopolitical concern, and security-of-supply objectives, rather than with strategic competitiveness or climate mitigation. This contrast indicates that trade restrictions occupy a distinct position within the industrial-policy toolkit, one that is more tightly coupled to geoeconomic considerations.

Second, this association strengthens markedly after 2020. For both import and export restrictions, the number of industrial actions justified on security-related grounds rises sharply in the 2020–2022 and 2023–2024 periods, while competitiveness- and climate-related justifications remain limited or decline in relative importance. This shift mirrors the broader reframing of industrial policy motives documented in Stylised Fact 3, but it is considerably more pronounced for trade restrictions than for subsidies, indicating that security rationales are disproportionately channelled through border and flow-controlling instruments.

In the United States, this pattern is especially concentrated. For import restrictions, the average annual number of industrial actions citing national security or geopolitical concern increases sharply after 2017 and remains high through 2023–2024. Export restrictions display an even stronger concentration: by 2020–2022 and 2023–2024, the majority of US export controls with stated motives are explicitly justified on national security grounds, with only a residual share attributed to resilience or other objectives. This concentration reflects the logic of recent US export-control regimes targeting advanced semiconductors, computing equipment, and related inputs, which are framed as instruments to constrain adversarial capabilities and protect dual-use technologies (Bureau of Industry and Security, 2022, 2023; Goldberg et al., 2024).

The European Union exhibits a related but institutionally distinct pattern. Security and geopolitical motives become increasingly prominent after 2020, but trade restrictions are more frequently framed in terms of resilience and security of supply than in terms of narrowly defined national security. This is particularly evident for import restrictions in 2020–2022, where industrial actions linked to securing access to critical inputs account for a substantial share of motive-tagged measures. This framing is consistent with EU initiatives aimed at reducing dependency on concentrated suppliers and managing supply-chain vulnerabilities, as articulated in the Critical Raw Materials Act and the EU’s broader economic security strategy (European Commission, 2024a, 2025).

China displays a delayed but convergent trajectory. Prior to 2020, a large share of Chinese trade restrictions—both import and export—lack explicit motive tags. After 2020, however, the number of restrictions citing national security, geopolitical concern, or security-of-supply objectives increases, particularly on the export side. The rise in export controls and licensing requirements on selected critical materials reflects a strategic effort to manage external dependencies while increasing leverage in upstream segments of global value chains. These measures are increasingly justified in terms of national security and supply stability rather than industrial competitiveness alone (Kelsall et al., 2024; CSIS, 2025).

Figures 5 and 6 confirm that trade restrictions play a distinct and increasingly central role within contemporary industrial policy. Unlike subsidies, which primarily reshape domestic cost structures and investment incentives, trade restrictions operate directly on cross-border flows, dependencies, and strategic chokepoints. As a result, they are more tightly coupled with geoeconomic objectives and more likely to generate international spillovers and retaliatory responses.

The growing alignment between trade restrictions and security or resilience rationales has important systemic implications. Security-based justifications tend to be less time-bound, less transparent, and less constrained by international trade disciplines than competitiveness- or climate-based rationales. This makes trade restrictions more durable, more difficult to unwind, and more prone to escalation. Combined with the persistence documented in Stylised Fact 1 and the motive shift identified in Stylised Fact 3, the evidence suggests that trade restrictions are increasingly used not as marginal policy adjustments, but as core industrial actions for reconfiguring global economic interdependence. This pattern is consistent with broader political-economy accounts that emphasise the growing use of security exceptions and non-justiciable policy space in international economic relations (Farrell & Newman, 2019; Hufbauer & Jung, 2023; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

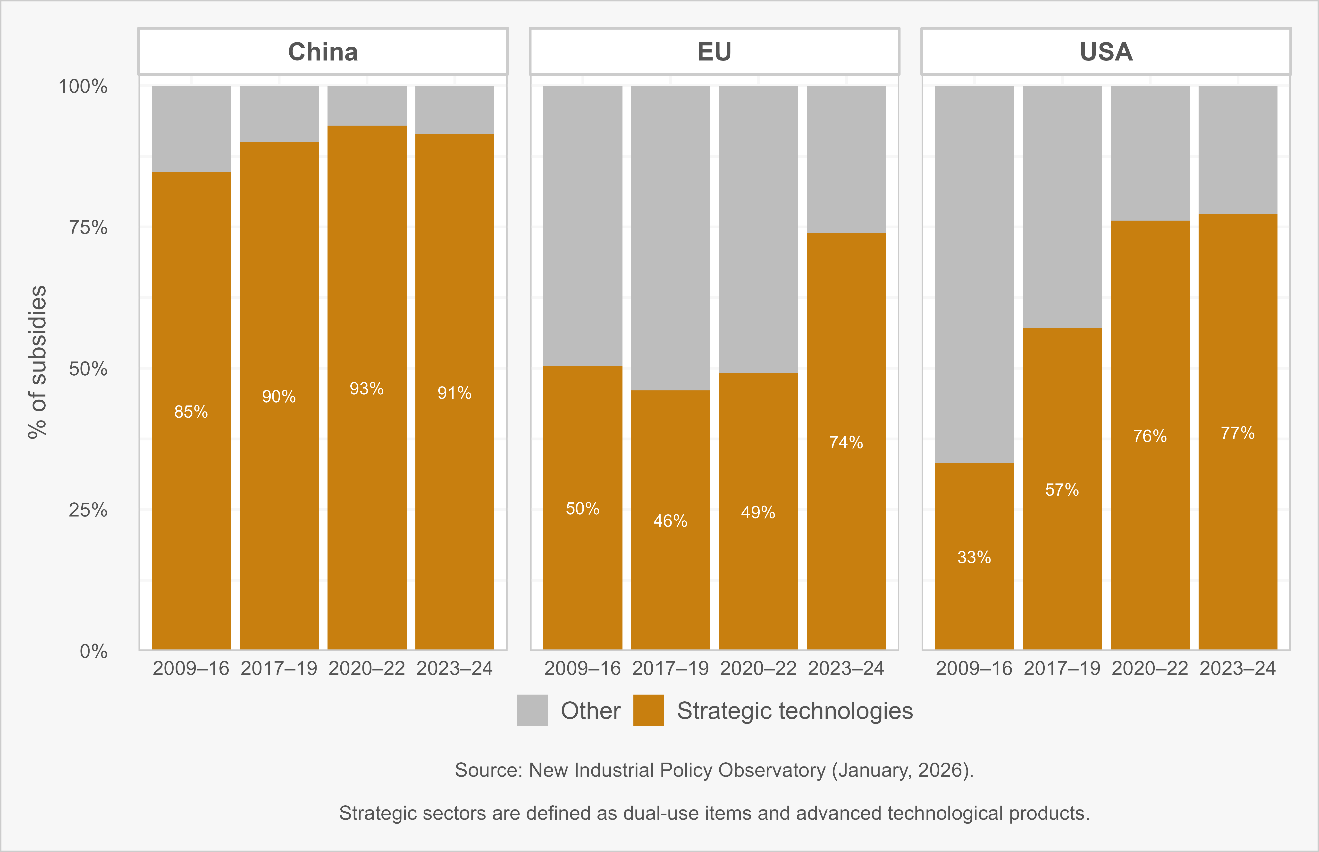

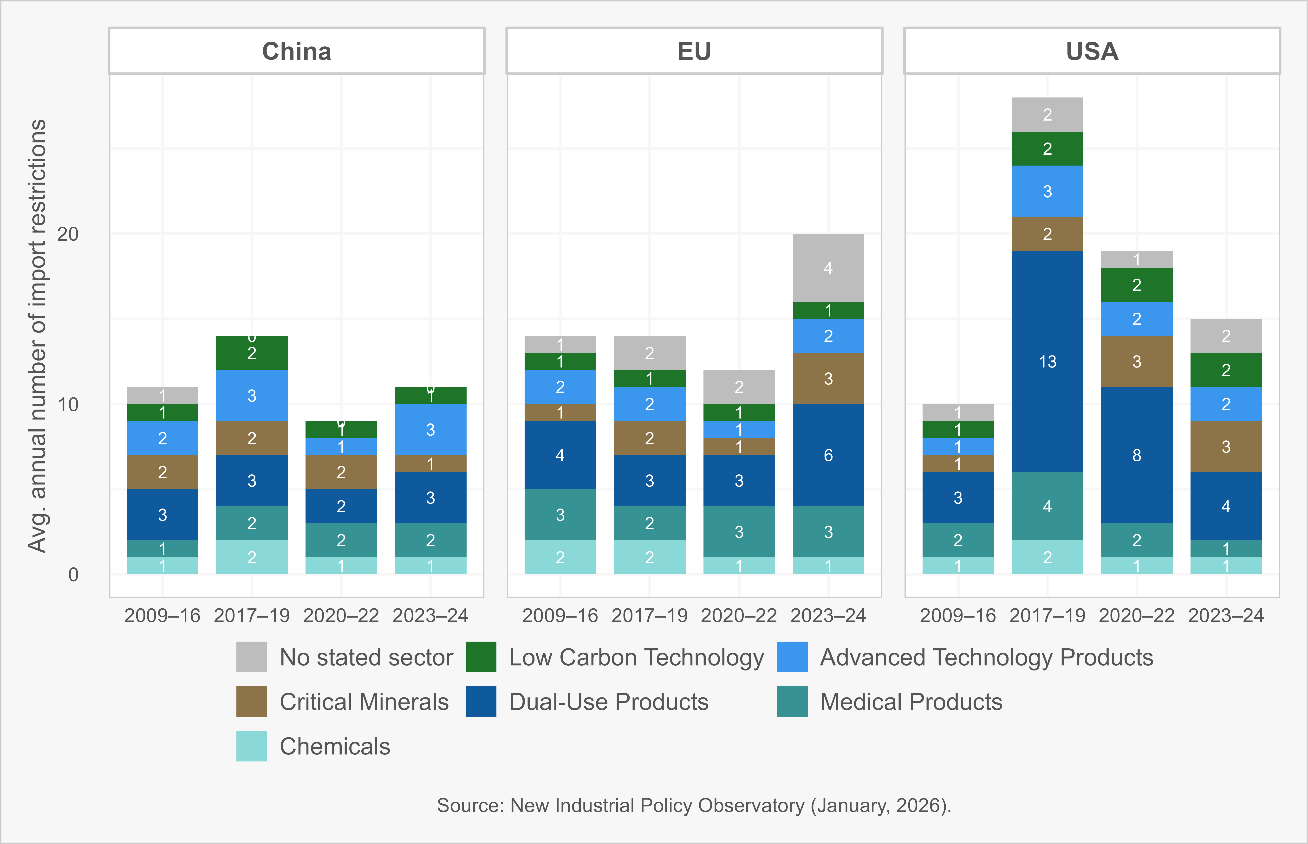

Across China, the European Union, and the United States, industrial actions increasingly concentrate on strategic chokepoints and dual-use technologies. While this convergence is pronounced by the early 2020s, it emerges through distinct national trajectories in timing, speed, and institutional logic.

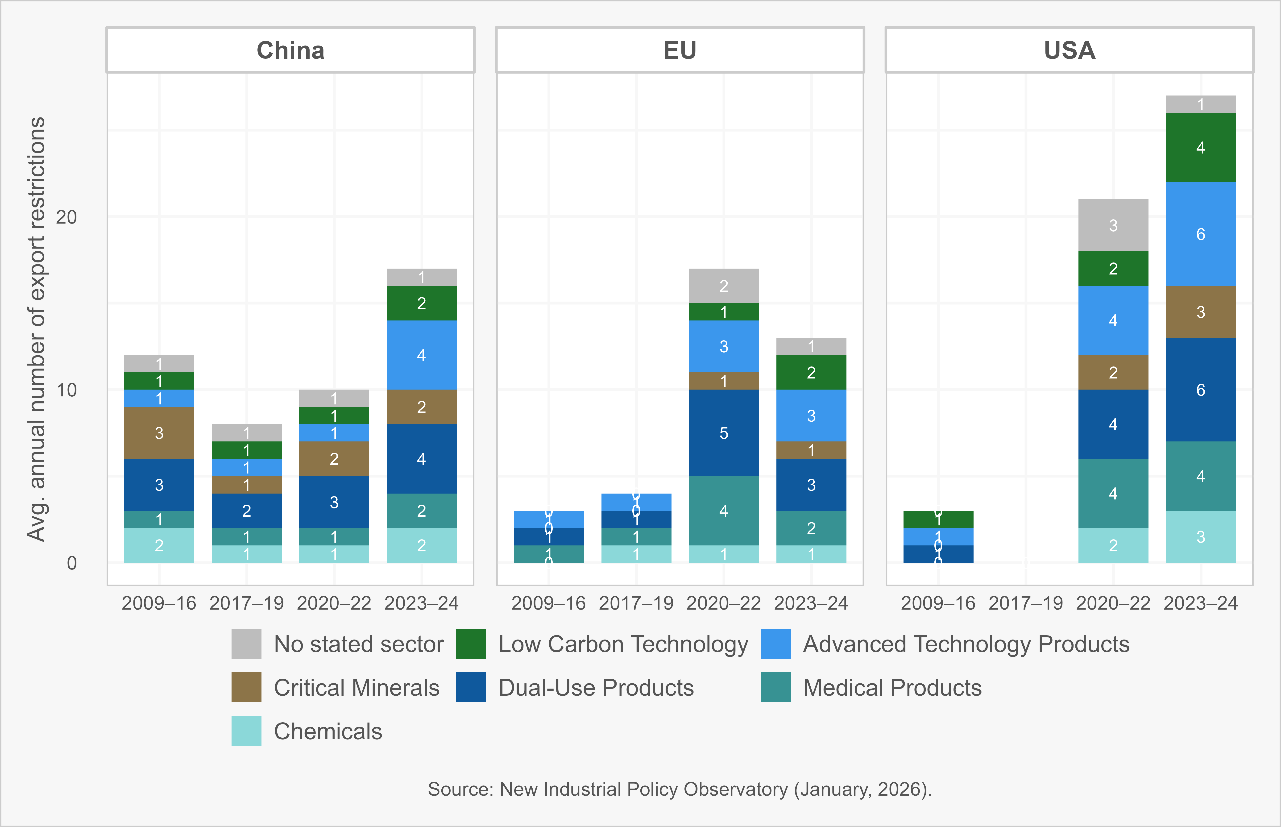

Figures 7–9 document the sectoral composition of industrial actions across three instrument categories: subsidies (Figure 7), import restrictions (Figure 8), and export restrictions (Figure 9). Strategic sectors are defined to include dual-use products and advanced technological goods. Across all three instruments, the share of industrial actions targeting strategic sectors rises markedly over time—particularly after 2020—and accounts for a large majority of activity by 2023–2024 in all three jurisdictions.

For subsidy-based industrial actions, Figure 7 shows that strategic sectors already account for a large share of activity in China throughout the sample, exceed three-quarters of US subsidies by 2020–2022, and rise sharply in the European Union after 2020, reaching comparable levels by 2023–2024. Figures 8 and 9 indicate that import- and export-restricting industrial actions are even more tightly concentrated in strategic sectors, especially in the United States and, increasingly, in the European Union after 2020. The evidence points to a broad reorientation of industrial policy toward sectors that take central positions in global value chains and where dependence generates both vulnerability and leverage.

China exhibits early and persistent strategic targeting. Already in 2009–2016, more than four-fifths of Chinese subsidy-based industrial actions target strategic technologies, with this share rising further and stabilising above 90 percent from 2017 onward. Figures 8 and 9 show that Chinese import and export restrictions are also heavily concentrated in strategic sectors throughout the sample. This pattern is consistent with an approach that treats trade measures as complements to long-term upgrading, capacity-building, and self-reliance strategies, particularly in upstream segments of global production networks (Naughton, 2021; Goldberg, Juhász & Lane, 2024).

The United States follows a different trajectory. In 2009–2016, only around one-third of US subsidy-based industrial actions target strategic sectors. This share rises sharply after 2017 and reaches roughly three-quarters by 2020–2022, increasing further in 2023–2024. The concentration is even stronger for trade-related industrial actions. Figures 8 and 9 show that US import and export restrictions are disproportionately focused on dual-use and advanced technology products, with the sharpest increases occurring after 2018 and intensifying after 2020. This pattern aligns with a shift from competitiveness-oriented support toward a security-driven industrial strategy, in which chokepoints—upstream technologies, critical inputs, and enabling infrastructure—become primary policy targets (Farrell & Newman, 2019; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

The European Union displays delayed but accelerating convergence. Throughout 2009–2019, EU industrial actions remain more evenly distributed across strategic and non-strategic sectors, with no sustained upward trend in strategic concentration. A clear break occurs after 2020 and becomes most pronounced after 2023, when the share of EU subsidy-based industrial actions targeting strategic technologies rises sharply toward three-quarters in Figure 7. Figures 8 and 9 show a parallel reorientation in trade-related industrial actions, with import and export restrictions increasingly concentrated in strategic sectors in the post-2020 period. This shift reflects the EU’s gradual move toward a strategic autonomy and resilience framework, particularly focused on upstream inputs relevant for clean technologies, advanced manufacturing, and critical raw materials (European Commission, 2023a, 2024a).

Figures 7–9 show a clear pattern of convergence by the early 2020s: China leads with early and persistent strategic targeting; the United States catches up rapidly through a sharp post-2017 pivot; and the European Union follows with delay and institutional adaptation. By 2023–2024, however, all three jurisdictions exhibit a similar sectoral configuration in which subsidies and trade restrictions are concentrated in sectors that sit at the centre of global value chains and where dependence generates strategic vulnerability or leverage.

As a result, exposure to industrial policy for firms and jurisdictions is increasingly determined by position within chokepoint ecosystems—such as semiconductors, advanced electronics, batteries, critical minerals, industrial machinery, and other dual-use supply chains—rather than by nationality alone. In these sectors, subsidies, trade restrictions, screening mechanisms, and regulatory conditionalities are most likely to cluster simultaneously, amplifying both policy effectiveness and the risk of international spillovers and retaliation.

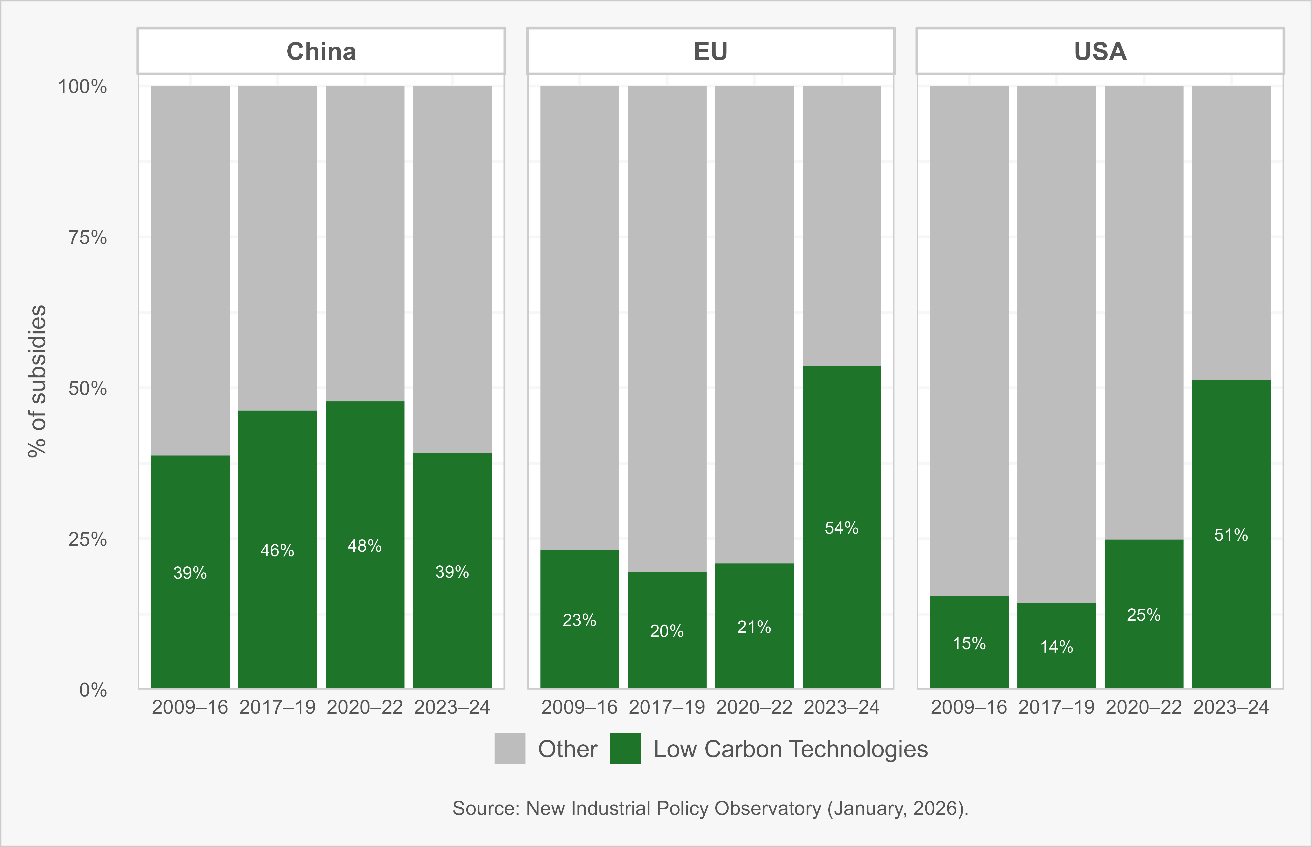

Subsidy-based industrial actions targeting low-carbon technologies expand across China, the European Union, and the United States over 2009–2024. China emerges as an early and persistent first mover, while the European Union and the United States scale up green industrial subsidies sharply only after 2020.

Figure 10 reports the percentage of subsidy-based industrial actions targeting low-carbon technologies across the three jurisdictions, grouped into four sub-periods. Two features stand out. First, China maintains a consistently high share of green-targeted subsidies throughout the entire sample. Second, both the European Union and the United States exhibit a delayed but rapid expansion of green industrial actions after 2020, leading to partial convergence in levels by the end of the period.

China’s position as a first mover is evident early on. Already in 2009–2016, approximately 40 percent of Chinese subsidy-based industrial actions target low-carbon technologies. This share increases further in 2017–2019 and peaks around 2020–2022, before stabilising in 2023–2024. The persistence of a high green share over more than a decade indicates that low-carbon technologies have long been embedded in China’s industrial policy framework, particularly in renewable energy manufacturing, electric vehicles, batteries, and associated upstream inputs. The data therefore point to continuity rather than abrupt reorientation: China’s green industrial actions substantially predate the recent acceleration of climate-oriented industrial policy in advanced economies, consistent with earlier evidence on China’s sustained support for clean-energy manufacturing and cost reduction (Nahm, 2017; Pegels & Lütkenhorst, 2014; Reguant, 2024).

By contrast, both the European Union and the United States display comparatively limited use of green industrial subsidies prior to 2020. During 2009–2019, low-carbon technologies account for around one-fifth or less of subsidy-based industrial actions in both jurisdictions. A clear break occurs after 2020. In the EU and the United States alike, the share of green-targeted subsidies rises sharply, exceeding 50 percent by 2023–2024. This late but rapid expansion reflects a deliberate effort to scale domestic clean-technology manufacturing capacity and to respond to perceived competitive disadvantages vis-à-vis early movers, particularly in batteries, electric vehicles, and renewable-energy supply chains (Allcott et al., 2024; Bistline et al., 2024).

Two mechanisms underpin this acceleration. First, the EU and the United States engage in explicit catching-up strategies, deploying large-scale subsidy programmes once fiscal, legal, and political constraints were relaxed in the wake of the pandemic and energy crisis. Second, the expansion of green industrial actions is facilitated by growing overlap in the product space. Many of the HS codes classified as low-carbon technologies—such as batteries, power electronics, grid components, and critical mineral inputs—are also classified as advanced or dual-use technologies. As a result, support for low-carbon sectors increasingly aligns with broader objectives related to technological capability, supply-chain resilience, and strategic autonomy, blurring the boundary between climate policy and security-oriented industrial strategy (Goldberg, Juhász & Lane, 2024; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

The evidence shows that green industrial policy is not an isolated domain but an integral component of contemporary industrial strategy. China’s early and persistent engagement contrasts with the late but rapid scale-up in the European Union and the United States, producing partial convergence in sectoral targeting by the early 2020s. This convergence reinforces the broader pattern identified in Stylised Fact 5: low-carbon technologies increasingly occupy the intersection of climate objectives, industrial competitiveness, and strategic value-chain positioning

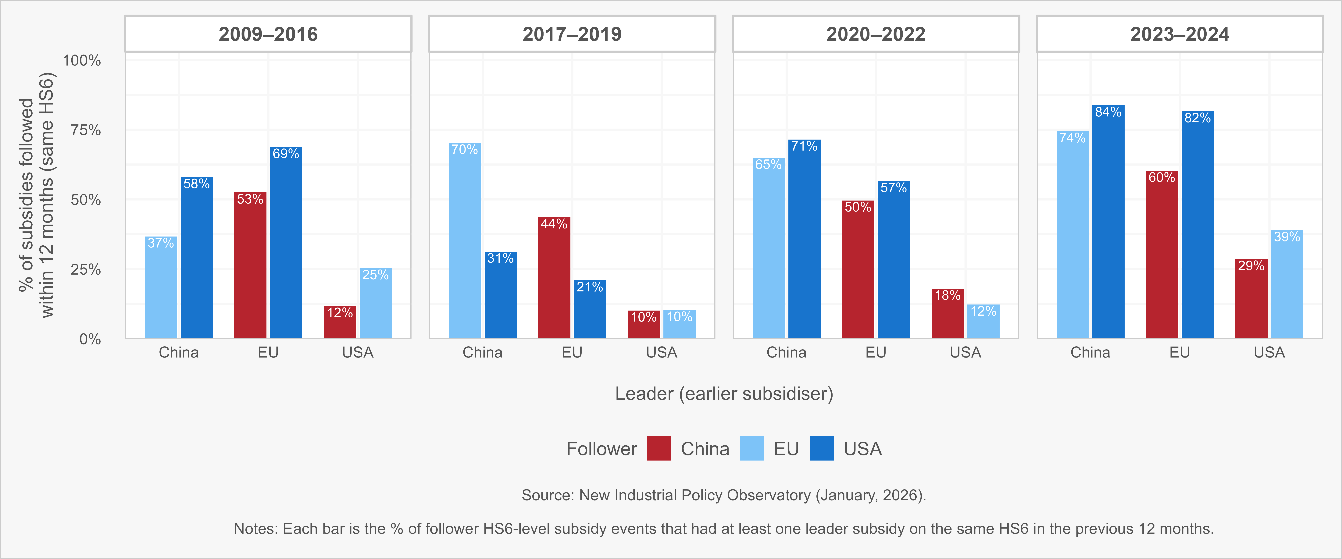

Subsidy-based industrial actions among China, the European Union, and the United States are embedded in a sequential and increasingly escalatory international policy environment. This escalation persists despite rising public debt and tightening fiscal conditions across all three jurisdictions.

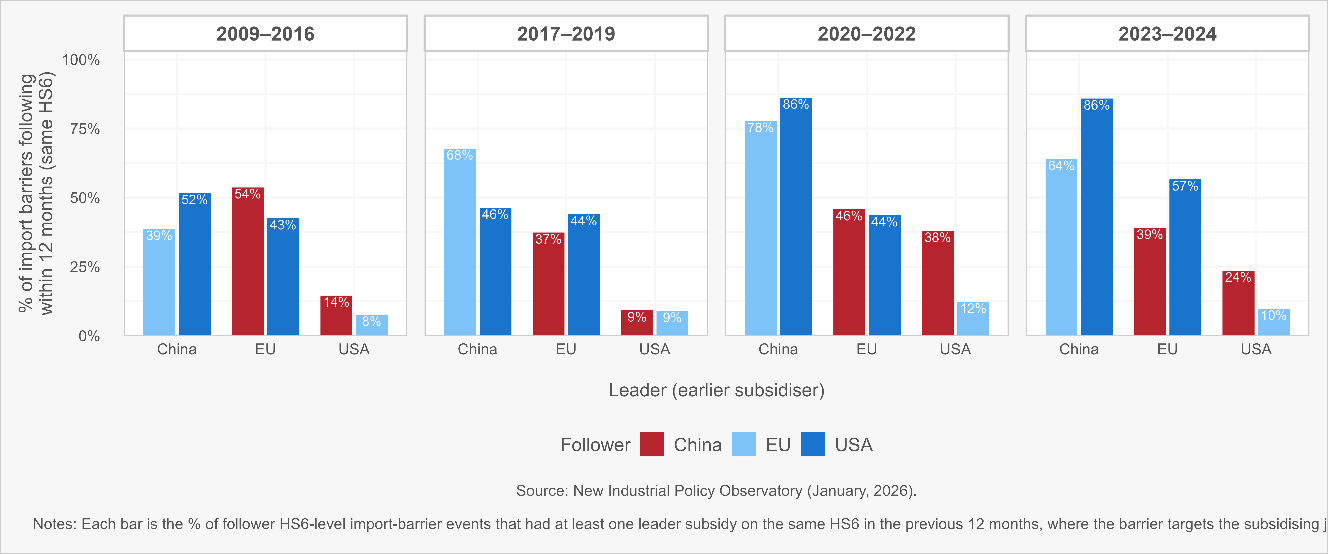

Figures 11 and 12 jointly document two related dynamics. Figure 11 focuses on short-horizon policy sequencing and reports the share of subsidy-based industrial actions adopted by a “follower” jurisdiction within twelve months of a prior subsidy implemented by another major economy targeting the same HS6 product. This measure captures rapid policy response and strategic interaction rather than long-run convergence. Figure 12 places these dynamics in fiscal context, comparing annual subsidy activity with general government debt as a percentage of GDP in each jurisdiction.

Figure 11 shows that subsidy following is already substantial prior to the recent escalation of trade and technology tensions. Between 2009 and 2016, roughly one-third to two-thirds of subsidy-based industrial actions across the Big Three occur within twelve months of a foreign subsidy targeting the same product. Even in this earlier period, subsidies frequently emerge in an internationally competitive context rather than as isolated domestic initiatives, consistent with evidence that industrial policy spillovers operate rapidly through expectations and investment-location decisions (Evenett et al., 2024; Cen et al., 2024).

Sequential behaviour intensifies during 2017–2019, coinciding with the escalation of US–China trade tensions and the growing politicisation of strategic supply chains. The sharpest increase occurs after 2020. In the 2020–2022 and 2023–2024 periods, following rates frequently exceed 60–80 percent, particularly when China or the United States acts as the initial subsidiser. The European Union appears both as a frequent follower and, increasingly, as a leader, indicating a pattern of mutual responsiveness rather than unilateral reaction. This configuration is consistent with emerging evidence of subsidy races in strategic sectors, where governments interpret large foreign subsidy announcements as signals requiring rapid countervailing action (Goldberg, Juhász & Lane, 2024; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

These patterns suggest that subsidies diffuse quickly across jurisdictions through overlapping and sequential responses. Governments appear to treat major subsidy announcements by peers as immediate coordination or competition signals within narrowly defined product spaces. The resulting behaviour is consistent with a competitive logic in which perceived first-mover advantages raise the expected cost of inaction and shorten policy response horizons, reinforcing escalation dynamics rather than dampening them.

Figure 12 shows that this escalation unfolds against a backdrop of tightening fiscal conditions. In China, subsidy activity rises steadily from 2009 onward and accelerates after 2018, while government debt increases persistently over the same period. In the European Union, subsidy announcements surge sharply after 2020, even as debt ratios rise following the pandemic and the energy-price shock. In the United States, large post-2018 and post-2020 subsidy expansions coincide with a marked increase in public debt that remains elevated through the early 2020s. Across all three jurisdictions, rising subsidy activity does not coincide with improving fiscal space.

Figures 11 and 12 together indicate that subsidy expansion is not primarily driven by cyclical slack or temporary fiscal capacity. Instead, it reflects the prioritisation of strategic industrial positioning even under increasingly binding budget constraints. Fiscal discipline does not appear to operate as an immediate brake on subsidy competition among major economies, echoing concerns that strategic and security considerations increasingly dominate conventional cost–benefit and budgetary calculus (Pack & Saggi, 2006; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

This stylised fact points to an industrial-policy environment that is not only interventionist but also contagious. A large subsidy programme in one major economy raises the probability of follow-on support elsewhere in the same product space within a short time horizon. As a result, expected profitability, location incentives, and capacity planning can shift rapidly, even in the absence of changes in underlying demand or technology. For firms, investment decisions increasingly require anticipating policy reactions across jurisdictions rather than evaluating support measures in isolation. For policymakers, the evidence suggests that the effective constraint on subsidy escalation is likely to be political and strategic rather than fiscal—at least until accumulated fiscal costs, trade distortions, or retaliatory dynamics trigger adjustment at the system level.

Foreign subsidy-based industrial actions are frequently followed by import-restricting industrial actions targeting the subsidising jurisdiction in the same product space. This sequencing strengthens over time and is most pronounced in large domestic markets.

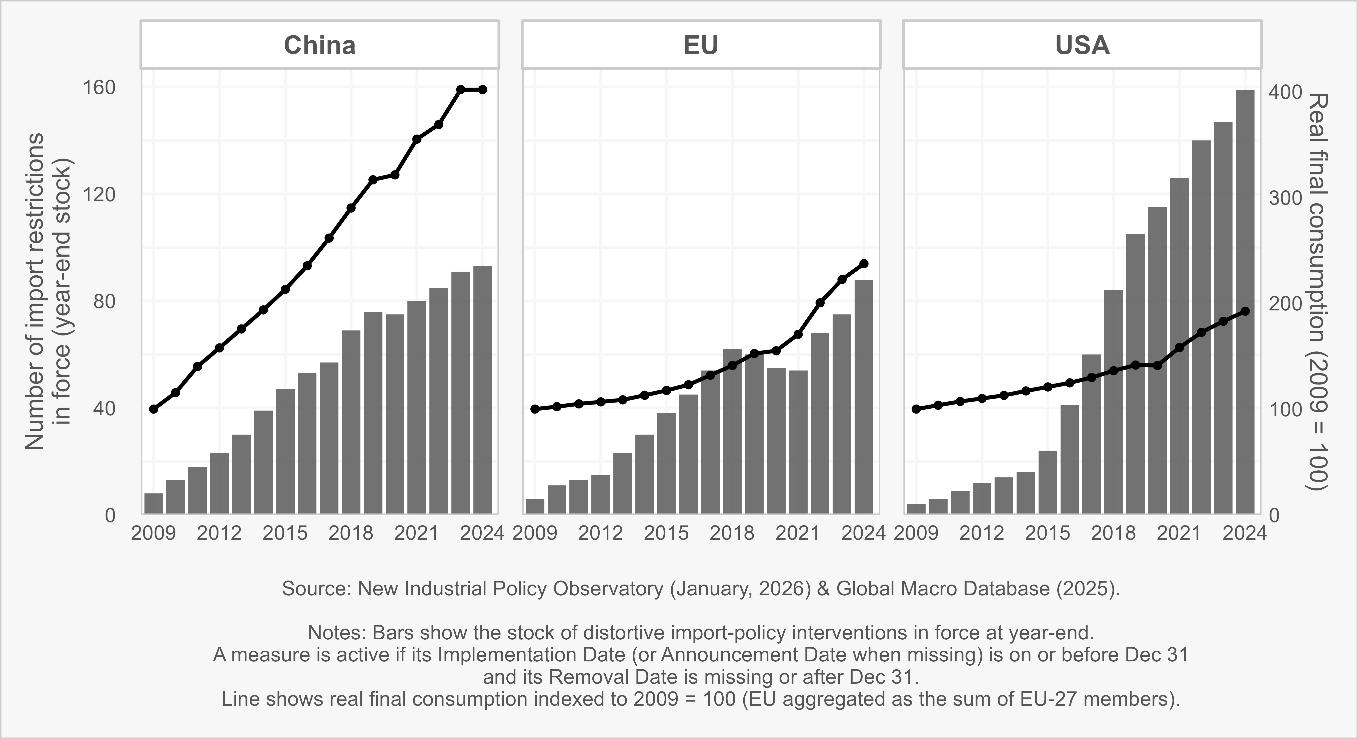

Figures 13 and 14 document the relationship between upstream subsidisation and downstream import restriction. Figure 13 reports, for each leader–follower combination, the share of HS6-level import-restricting industrial actions adopted within twelve months after a foreign subsidy targeting the same product and the same trading partner. This measure captures short-horizon policy sequencing between subsidies and border measures, rather than long-run correlation or structural protection levels.

The evidence shows that import barriers are frequently imposed shortly after subsidies abroad. Even during the 2009–2016 period, a substantial share of import-restricting industrial actions across the Big Three occurs within twelve months of a foreign subsidy in the same product category. This linkage intensifies during 2017–2019 and rises sharply after 2020. By 2023–2024, in several leader–follower pairs more than half—and in some cases a large majority—of import barriers are associated with a foreign subsidy adopted in the preceding year. The pattern is particularly strong when China or the United States acts as the initial subsidiser, but it is also clearly visible when the European Union is the leader.

These patterns indicate that subsidies are not treated solely as domestic competitiveness measures, but frequently trigger defensive responses at the border. Import barriers appear to function as instruments for managing the international spillovers of foreign industrial support, especially in sectors where subsidies are perceived to distort market access or competitive conditions. This sequencing is consistent with empirical evidence that governments respond to foreign industrial policy through trade-restrictive instruments when domestic adjustment costs or political pressures are salient (Evenett et al., 2025; Rickard, 2025).

Figure 14 shows that the accumulation of import barriers is systematically associated with domestic market size, particularly in China and the United States. Larger domestic markets sustain higher numbers of import-restricting industrial actions in force over time. This pattern reflects the fact that sizeable internal demand can support production once shielded from foreign competition, making protection economically viable and politically sustainable. The European Union follows a similar but more gradual trajectory, consistent with a more fragmented internal market and tighter legal and political constraints on sustained border insulation.

Figures 13 and 14 show that exposure to foreign subsidies is not only a cost-competition issue but also a market-access risk. Exporters operating in strategically contested sectors face the greatest uncertainty precisely in the largest markets, where subsidies are most likely to be followed by import barriers within a short time horizon. For domestic firms, the policy environment increasingly consists of combined packages of support and protection that reset competitive baselines and investment incentives simultaneously.

These dynamics help explain why trade frictions have intensified alongside—rather than in opposition to—the expansion of industrial subsidies. Subsidies abroad raise the likelihood of import barriers at home, particularly where domestic market size makes protection feasible. As a result, border measures remain a central instrument for managing the international spillovers of industrial policy, reinforcing the interaction between subsidy competition and defensive trade policy documented in earlier stylised facts.

Defensive trade industrial actions implemented by China, the European Union, and the United States are increasingly directed toward rival major economies. This directional concentration intensifies after 2016 and becomes particularly pronounced after 2020.

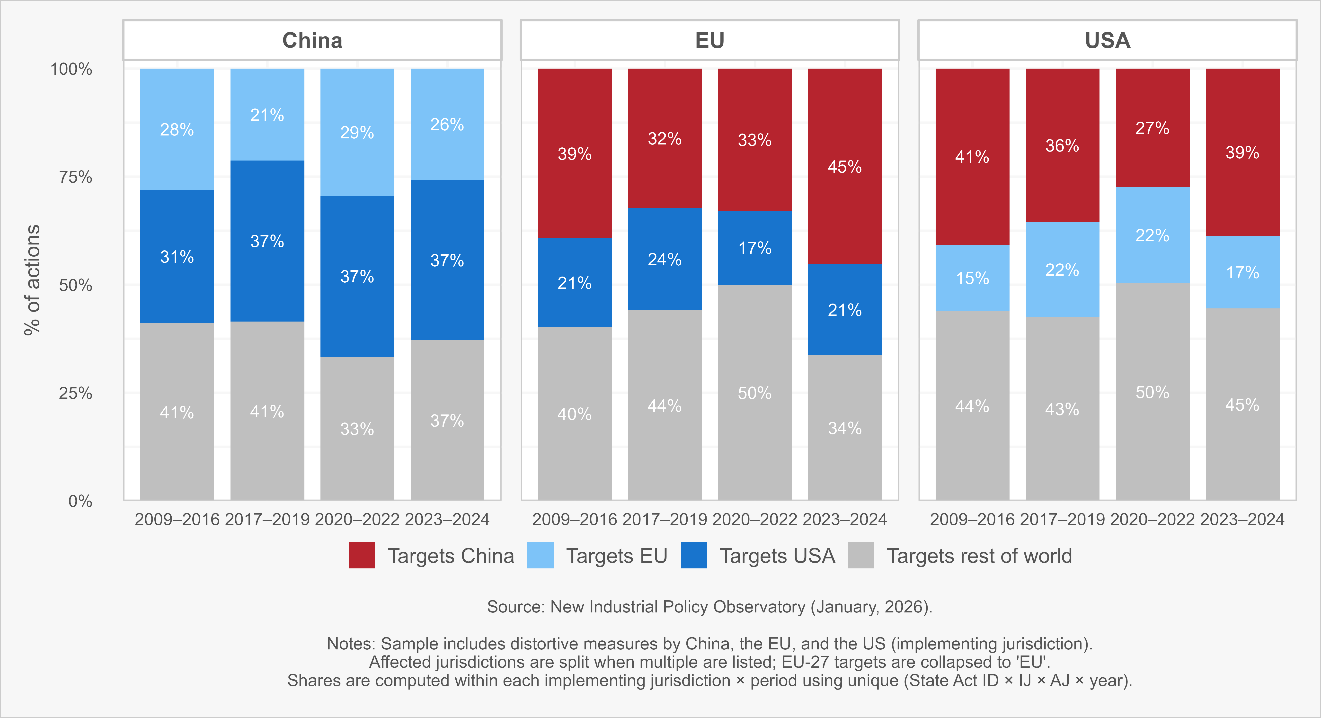

Figure 15 examines the directional structure of import-barrier and trade-defence industrial actions over 2009–2024. Rather than focusing on aggregate volumes, the figure reports the distribution of affected jurisdictions—distinguishing between measures targeting China, the European Union, the United States, and the rest of the world—within each implementing jurisdiction and time period. This approach highlights how defensive trade actions are allocated across partners, rather than how frequently they are used overall.

Three empirical patterns stand out. First, defensive trade policy is not globally diffuse even in the early period. Between 2009 and 2016, roughly one-half to two-thirds of defensive trade industrial actions implemented by each of the Big Three already target other major economies rather than the rest of the world. Partner-specific targeting is therefore a persistent feature of defensive instruments, predating the overt escalation of trade and technology conflicts in the late 2010s.

Second, directional concentration intensifies markedly after 2016 and sharpens further after 2020. The European Union exhibits a pronounced increase in the share of defensive trade industrial actions targeting China in 2023–2024, accompanied by a corresponding decline in measures directed at the rest of the world. The United States follows a similar trajectory, with China absorbing a growing share of US defensive trade actions from 2017 onward. China’s own defensive measures remain consistently focused on the United States and the European Union throughout the sample, with little evidence of diversification toward third-country targets.

Third, this shift operates primarily through reallocation rather than generalised expansion. The rising share of rival-directed defensive actions is mirrored by a contraction in the “rest-of-world” category, indicating a sharpening of focus rather than a uniform increase in protection. Defensive trade policy thus becomes increasingly concentrated on a small number of strategically salient bilateral relationships, rather than being applied broadly across trading partners.

Import barriers and trade-defence measures are therefore increasingly deployed as targeted instruments aimed at specific counterparts perceived as sources of strategic risk, unfair competition, or geopolitical vulnerability. The rival-directed nature of these actions amplifies their systemic impact. Measures aimed at major economies are more likely to generate retaliation, escalation, and policy feedback than actions directed at smaller or less integrated partners. As a result, directional targeting increases the strategic salience of defensive instruments even when aggregate levels of protection do not rise proportionally, consistent with accounts of rivalry-driven trade conflict and geoeconomic competition (Farrell & Newman, 2019; Evenett et al., 2025; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

Figure 15 suggests that contemporary defensive trade policy is increasingly organised around rivalry rather than openness management. The concentration of defensive actions within China–EU–US relationships implies that the evolution of the global trading system is being shaped disproportionately by intensified frictions among a small number of dominant actors, with implications for escalation dynamics, cooperation, and the stability of trade governance.

Since 2020, trade-restricting industrial actions exhibit a clear asymmetry in persistence. Export restrictions have become markedly more durable, while import restrictions—though still widely used—remain comparatively less persistent. Subsidy-based industrial actions continue to be uniformly long-lived, reflecting programme design rather than a shift in trade-policy logic.

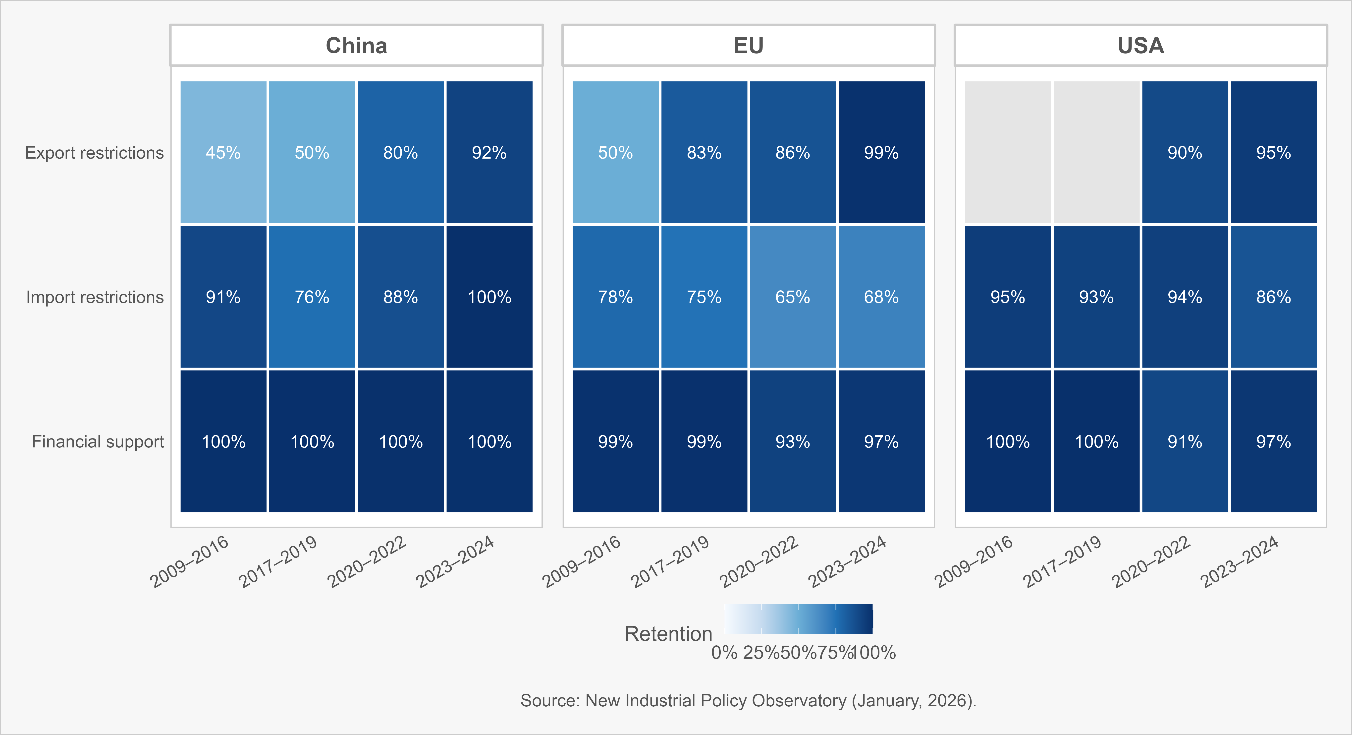

Figure 16 reports the share of trade-restricting and subsidy-based industrial actions that remain in force twelve months after implementation, disaggregated by implementing jurisdiction and adoption cohort. By focusing on retention rather than adoption, the figure captures how long different policy instruments continue to shape competitive conditions once introduced.

Three patterns stand out. First, export restrictions become increasingly persistent after 2020 across all three jurisdictions. In the 2009–2016 and 2017–2019 cohorts, roughly one-half of export restrictions remain in force after twelve months. By contrast, in the 2020–2022 and especially the 2023–2024 cohorts, retention rates rise sharply—exceeding 80–90 percent in China and the United States and approaching full persistence in the European Union. This constitutes a discrete upward shift in the durability of export controls, licensing regimes, and associated regulatory measures.

Second, while import-restricting industrial actions remain prevalent, their twelve-month retention rates do not increase in parallel with export restrictions. In the European Union, retention declines from around three-quarters before 2020 to roughly two-thirds in the post-2020 cohorts. In the United States, import restrictions remain relatively persistent but exhibit a modest decline in retention in the most recent cohort. China represents a partial exception, with high retention throughout the sample; even there, however, the contrast with the sharply rising persistence of export restrictions remains evident.

Third, subsidy-based industrial actions are almost universally persistent across all periods and jurisdictions, with twelve-month retention rates close to 100 percent throughout. This reflects the institutional design of subsidy programmes—multi-year grants, tax credits, and entitlement-based schemes—rather than a shift in the strategic logic governing trade instruments.

The divergence in persistence between export and import restrictions points to a reconfiguration of how trade instruments are used in the 2020s. Export restrictions increasingly function as long-horizon policy tools. Once imposed, export controls and associated regulatory regimes reshape investment decisions, sourcing strategies, and technological trajectories. As firms adapt supply chains, compliance systems, and production networks around these constraints, reversal becomes costly for both governments and industry, reinforcing persistence. This dynamic is consistent with analyses that emphasise the role of export controls in shaping long-term strategic interdependence and chokepoint power rather than short-term trade adjustment (Farrell & Newman, 2019; Hayakawa et al., 2023; Hoekman & Nelson, 2025).

Import restrictions, by contrast, are more often deployed as contingent defensive instruments. They respond to perceived import surges, subsidised competition, or short-term market disruption, and are typically embedded in institutional processes that mandate review, legal challenge, or negotiated adjustment. This makes them comparatively easier to recalibrate, replace, or unwind over time, even in an environment of heightened trade tension.

The evidence suggests that export-restricting industrial actions increasingly behave as regime characteristics—structural, persistent, and embedded in regulatory architecture—while import barriers, though economically consequential, remain more episodic and adjustable. For firms, export-control risk increasingly requires long-term strategic adaptation, shaping location decisions, technology choice, and supplier relationships. For the international trading system, the enduring reconfiguration of global competition is therefore being driven less by temporary border protection and more by sustained control over access to critical inputs, technologies, and strategic chokepoints.

This paper documents a structural transformation in the practice of industrial policy since 2009, with a pronounced acceleration after 2019 and a decisive reconfiguration after 2020. Using an extended New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) panel that focuses on industrial actions plausibly altering relative competitive conditions, the analysis shows that selective industrial policy has become more frequent, more persistent, and more strategically organised. What emerges is not a temporary deviation driven by crisis management, but a durable shift in how governments shape competition, production, and exposure to foreign firms.

Taken together, the ten stylised facts point to three defining features of contemporary industrial policy. First, intervention has scaled up and remained persistently high. Selective industrial actions no longer unwind once shocks recede; instead, they accumulate over time, creating a high-intervention baseline. Second, policy design has become increasingly strategic. Instruments, stated motives, and sectoral targeting converge on technologies and inputs that occupy central positions in global value chains. Security, resilience, and geopolitical rivalry now structure not only subsidy design, but also the use, sequencing, and persistence of trade-restricting instruments. Third, industrial policy operates in an explicitly international and interactive environment. Subsidies diffuse rapidly across jurisdictions through short-horizon follow-on responses; they are frequently followed by import barriers in large domestic markets; defensive measures are increasingly rival-directed; and export restrictions, once imposed, tend to persist. Together, these patterns describe a competitive and sequential policy equilibrium rather than a collection of independent national strategies.

The implications are consequential. For policymakers, the evidence suggests that industrial policy has moved beyond episodic market correction toward a standing system of market-shaping intervention. This shift raises the stakes for transparency, coordination, and institutional guardrails. As subsidies, trade restrictions, and export controls interact across borders, the central risk is not merely higher levels of protection, but cumulative distortion, escalation, and fragmentation concentrated in strategically salient sectors. Preserving scope for adjustment, limiting retaliatory spirals, and avoiding lock-in to inefficient or adversarial equilibria will be central challenges for economic governance in the years ahead.

The stylised facts also imply a fundamental change in the nature of competition. Competitive advantage is increasingly shaped not only by cost, technology, or scale, but by positioning within policy regimes. Market access, investment viability, and supply-chain resilience depend on eligibility rules, localisation requirements, exposure to export controls, and vulnerability to defensive measures in large markets. Industrial policy creates significant opportunities for firms embedded within preferred ecosystems, but it also raises the cost of operating across rival blocs and heightens the strategic importance of upstream chokepoints. In this environment, geopolitical and policy literacy are no longer peripheral considerations; they are core strategic capabilities.

The broader implication is not the end of globalisation, but its reorganisation. Cross-border production and exchange continue, yet they are increasingly structured by selective industrial actions that determine who competes, where, and under what conditions. Industrial policy has become a central mechanism through which governments shape market structure and competitive outcomes. Understanding its scale, structure, and dynamics is therefore essential for analysing contemporary trade, investment, and the evolving architecture of the global economy.

From a trade-governance perspective, the findings point not to a sudden collapse of the multilateral trading system, but to a gradual reconfiguration of how trade is governed. As subsidies, security-based trade restrictions, and rival-directed defensive measures proliferate, the locus of competition increasingly shifts outside the core disciplines of tariff bindings and non-discrimination. The WTO remains relevant, but more as a reference point and procedural framework than as a binding constraint on strategic industrial policy. Understanding this shift—from rule-based liberalisation toward managed, security-conditioned competition—is essential for assessing the future trajectory of the global trading system.

Aghion, P., Dechezleprêtre, A., Hémous, D., Martin, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). Carbon taxes, path dependency, and directed technical change: Evidence from the auto industry. Journal of Political Economy, 124(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1086/684581

Allcott, H., Kane, R., Maydanchik, M. S., Shapiro, J. S., & Tintelnot, F. (2024). The effects of “Buy American”: Electric vehicles and the Inflation Reduction Act (NBER Working Paper No. 33032). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33032

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The impact of the 2018 trade war on U.S. prices and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.187

Antràs, P. (2020). De-globalisation? Global value chains in the post-COVID-19 age (NBER Working Paper No. 28115). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28115

Benitah, M. (2019). The WTO law of subsidies: A comprehensive approach. Wolters Kluwer.

Bickenbach, F., Liu, W.-H., & Rosendahl, C. (2024). EU concerns about Chinese subsidies: What the evidence suggests. Intereconomics, 59(4), 213–220.

Bistline, J., Mehrotra, N., & Wolfram, C. (2023). Economic implications of the climate provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act (NBER Working Paper No. 31267). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31267

Bown, C. P., Irwin, D. A., & Lovely, M. E. (2025). Industrial policy through the CHIPS and Science Act: A preliminary report. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Bureau of Industry and Security. (2022). Implementation of additional export controls: Certain advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing items; supercomputer and semiconductor end use; entity list modification. Federal Register.

Bureau of Industry and Security. (2023). Semiconductor manufacturing equipment controls: Interim final rule. U.S. Department of Commerce.

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2025). Beyond rare earths: China’s growing threat to gallium supply chains. CSIS.

Chapman, S., Dedet, G., & Lopert, R. (2022). Shortages of medicines in OECD countries (OECD Health Working Papers No. 137). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b5d9e15d-en

Chen, Z., He, Z., & Liu, C. (2024). Industrial subsidies, firm performance, and market structure: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 52(1), 1–26.

Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2019). The return of the policy that shall not be named: Principles of industrial policy (IMF Working Paper No. 19/74). International Monetary Fund.

Choi, J., & Levchenko, A. A. (2025). The long-term effects of industrial policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 152, 103779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2025.103779

Cen, X., Fos, V., & Jiang, W. (2023). How do U.S. firms withstand foreign industrial policies? (SSRN Working Paper No. 4418407). SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4418407

Dechezleprêtre, A., & Sato, M. (2017). The impacts of environmental regulations on competitiveness. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 11(2), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rex013

European Commission. (2020). Temporary framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak (2020/C 91 I/01). Official Journal of the European Union.

European Commission. (2022). Temporary crisis framework for State aid measures to support the economy following the aggression against Ukraine by Russia. Official Journal of the European Union.

European Commission. (2023a). A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age (COM(2023) 62 final).

European Commission. (2023b). Net-Zero Industry Act (COM(2023) 161 final).

European Commission. (2024). European Critical Raw Materials Act.

European Commission. (2025). RESourceEU: New measures to secure raw materials and strengthen the EU’s economic security.

Evenett, S. J., & Fritz, J. (2023). Subsidies and state interventions: Evidence from the Global Trade Alert. CEPR Press.

Evenett, S. J., Jakubik, A., Martín, F., & Ruta, M. (2024). The return of industrial policy in data. The World Economy, 47(7), 2762–2788. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13608

Evenett, S. J., Jakubik, A., Kim, J., Martín, F., Pienknagura, S., Ruta, M., Baquie, S., Huang, Y., & Machado Parente, R. (2025). Industrial policy since the Great Financial Crisis (IMF Working Paper No. 25/222). International Monetary Fund.

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79.

Goldberg, P. K., & Maggi, G. (1999). Protection for sale: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(3), 463–475.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84(4), 833–850.

Handley, K., & Limão, N. (2017). Policy uncertainty, trade, and welfare. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2731–2783. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141419

Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633.

Hoekman, B., & Nelson, D. (2025). Industrial policy and international cooperation. World Trade Review, 24(2), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745624000673

Huang, Y., Li, H., Lin, C., & Wang, Y. (2023). Does “Made in China 2025” work for China? (NBER Working Paper No. 30676). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hufbauer, G. C., & Jung, E. (2023). Industrial policy, subsidies, and WTO rules: A pragmatic reform agenda. Journal of International Economic Law, 26(4), 679–702.

Irwin, D. A. (2020). Clashing over commerce: A history of U.S. trade policy. University of Chicago Press.

Juhász, R., Lane, N., & Rodrik, D. (2024). The new economics of industrial policy. Annual Review of Economics, 16, 213–242.

Kelsall, C., Lee, B., & Ryan, M. (2024). China’s export controls on critical minerals—gallium, germanium and graphite. Bayes Centre for International Development.

Nahm, J. (2017). Renewable futures and industrial policy: Energy transitions in East Asia. Energy Policy, 101, 558–567.

Naughton, B. (2021). The rise of China’s industrial policy, 1978–2020. Asian Economic Policy Review, 16(2), 1–21.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Measuring distortions in international markets: The semiconductor value chain (OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 234). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/8fe4491d-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024). Quantifying the role of state enterprises in industrial subsidies (OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 282). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/49f39be1-en

Pegels, A., & Lütkenhorst, W. (2014). Is Germany’s energy transition a case of green industrial policy? Energy Policy, 74, 522–534.

Reguant, M. (2024). The role of industrial policy in the renewable energy sector. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(1), 47–70.

Rickard, S. J. (2025). Tariffs versus subsidies: Protection versus industrial policy. World Trade Review, 24(4), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474562510102X

Rodrik, D. (2004). Industrial policy for the twenty-first century (KSG Working Paper RWP04-047). Harvard Kennedy School.

Rotunno, L., & Ruta, M. (2024a). Trade implications of China’s subsidies (IMF Working Paper No. 24/180). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400286834.001

Rotunno, L., & Ruta, M. (2024b). Trade spillovers of domestic subsidies (IMF Working Paper No. 24/041). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400269486.001

Rubini, L. (2024). Retooling the regulation of net-zero subsidies: Lessons from the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. Journal of International Economic Law, 27(3), 441–470.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2015). Made in China 2025.

World Trade Organization. (2024). Trade policy review: China (WT/TPR/S/458).

Zhang, K. H. (2024). Geoeconomics of U.S.–China tech rivalry and industrial policy. Asia and the Global Economy, 4(1), 1–18.