From Subsidies to Sockets: Why Power Systems Now Decide Europe’s Industrial Future

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #82

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #82

Since 2021, electricity prices and grid constraints have become first-order execution risks for European industrial policy. In Europe’s market-based power system, industrial outcomes now depend less on subsidy availability than on whether firms can secure timely grid access and reliable electricity supply.

The rapid expansion of AI-related data centres provides a revealing stress-test. It shows that power availability—not capital or subsidies—is becoming the binding constraint on industrial activity

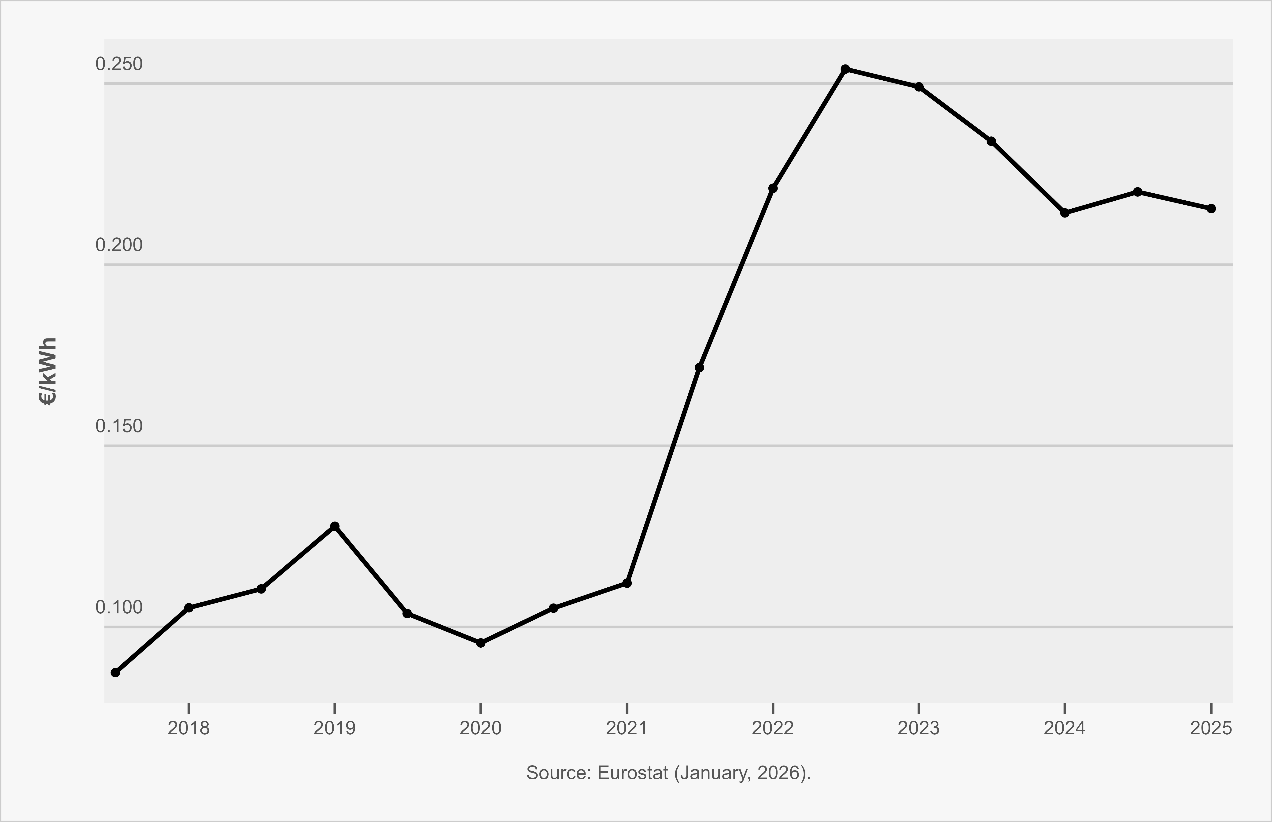

Electricity prices for non-household consumers rose sharply across Europe after 2021. As shown in Figure 1, industrial electricity costs increased markedly across Member States in the early 2020s, exposing energy-intensive and electrifying industries to severe price shocks.

At the same time, physical constraints in the electricity system have become binding. Grid congestion and connection delays are no longer abstract risks. In the Netherlands, electricity-network access has been formally rationed, with more than 11,900 businesses reportedly waiting for grid connections, illustrating how network saturation can directly constrain real-economy activity.[1] [2]

These constraints are now explicitly recognised at EU level. The European Commission’s European Grids Package identifies persistent bottlenecks caused by permitting delays, coordination failures and insufficient network investment.[3] Industrial policy outcomes increasingly hinge not only on subsidies, but on whether projects can secure grid connections and firm power on commercially viable timelines, especially in already saturated regions.

Firm behaviour since the energy shock shows how electricity prices and system constraints translate into production and investment outcomes.

Yara temporarily curtailed production at European plants, citing record-high natural gas prices, illustrating how energy costs force output reductions and increase reliance on imported intermediates.[4]

Primary aluminium production in Europe contracted sharply as smelters curtailed or shut down operations, with output falling by more than half since the onset of the energy crisis due to persistently high electricity prices.

The rapid expansion of AI and data-centre investment adds a large, concentrated electricity load to systems already constrained by grid capacity. The International Energy Agency projects that data centres will drive a significant share of Europe’s electricity-demand growth through 2030, making energy availability central to the region’s digital ambitions.[5]

Financial Times reporting highlights the growing difficulty of securing grid power for AI infrastructure, citing rising power density and intense, location-specific competition for connections.[6] BloombergNEF similarly projects strong growth in electricity demand from hyperscale and colocation data centres across Europe.[7]

Recent statements underscore that energy availability is becoming a decisive strategic variable. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has argued that energy costs will determine which countries win the AI race, explicitly linking competitiveness to the supply of affordable, reliable electricity.[8] In contrast, U.S. policymakers emphasise America’s infrastructure and resource advantages in meeting AI’s rising energy demand.[9] Industry analysis cited by Oilprice, drawing on JPMorgan estimates, suggests U.S. data-centre capacity could exceed 130 gigawatts by 2030, with power availability—not capital—identified as the binding constraint.[10]

AI therefore functions less as incremental demand than as a stress-test of energy systems, revealing whether industrial strategies are backed by deliverable grid access and firm power.

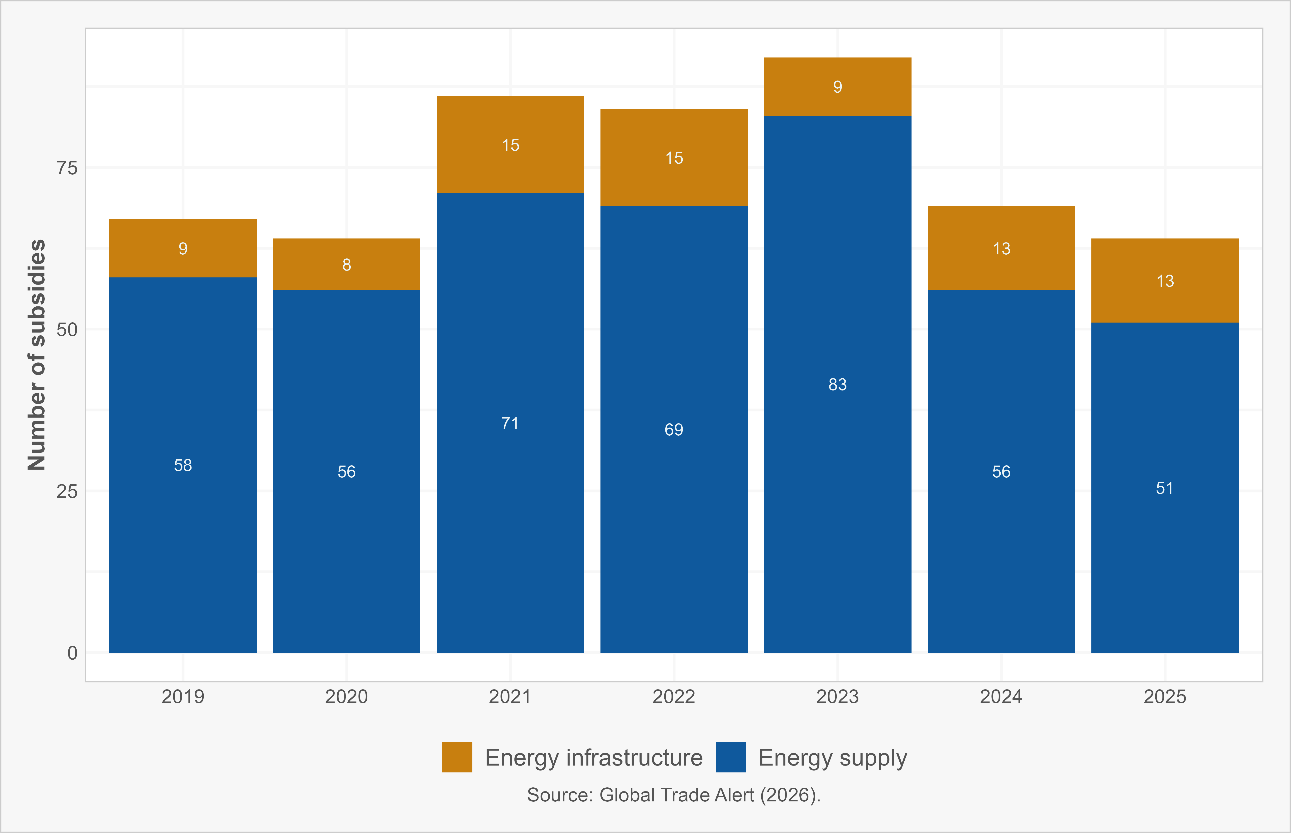

Energy-related policy interventions expanded after 2021. However, composition matters. As shown in Figure 2, energy supply measures consistently exceeded energy infrastructure measures between 2019 and 2025.

While the Commission’s grid initiatives target connection queues and permitting delays—implicitly recognising infrastructure as a binding constraint—most energy-related subsidies remain skewed toward expanding generation capacity rather than accelerating network build-out and connections. Infrastructure-focused interventions have increased but still represent a relatively small share of total energy support.[11] [12]

Electricity systems have become first-order constraints on European industrial strategy. Rising industrial electricity prices and binding grid bottlenecks are already shaping production and investment decisions.

Energy-price shocks force curtailment (Yara), persistently high electricity costs drive capacity contraction (aluminium) and AI intensifies these pressures. Across industry leaders and policymakers, the message converges: competitiveness in AI—and increasingly in advanced industry—depends on the ability to deliver affordable, reliable electricity at specific locations and on predictable timelines.

Subsidies alone cannot overcome these constraints. Without faster grid expansion, accelerated permitting and credible delivery of firm power, Europe risks substituting financial support for physical capability. The decisive margin of industrial competition has shifted from subsidies to sockets.

Fernando Martín is Associate Director at Global Trade Alert, leading the Analytics team, and Geopolitical Strategist at IMD