One By One: Bringing ASEAN Trading Nations into Washington’s Orbit

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #75

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #75

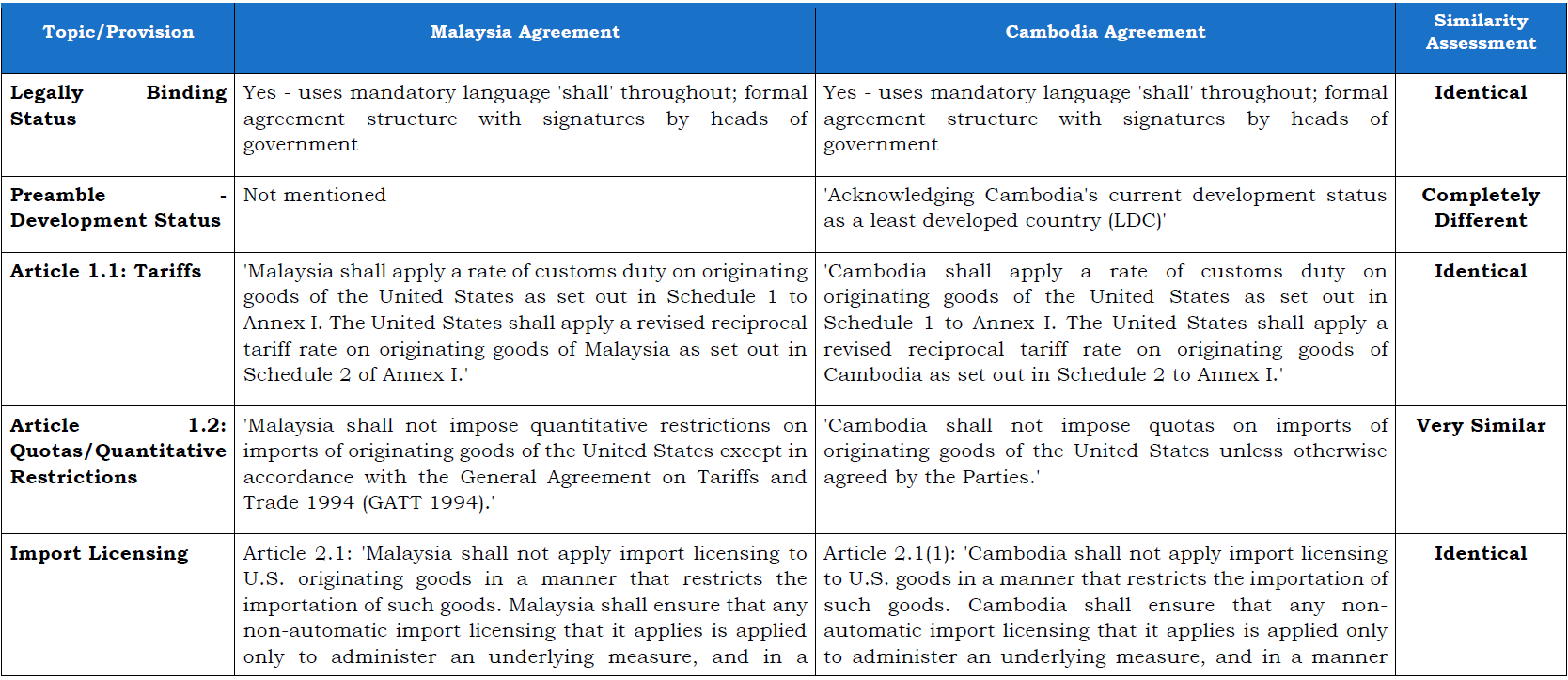

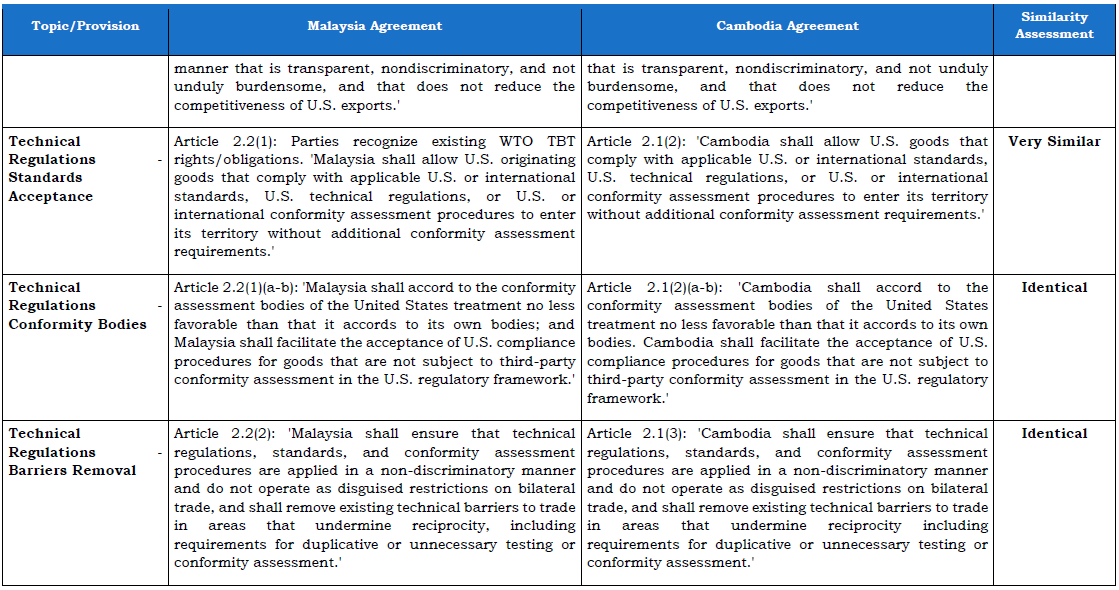

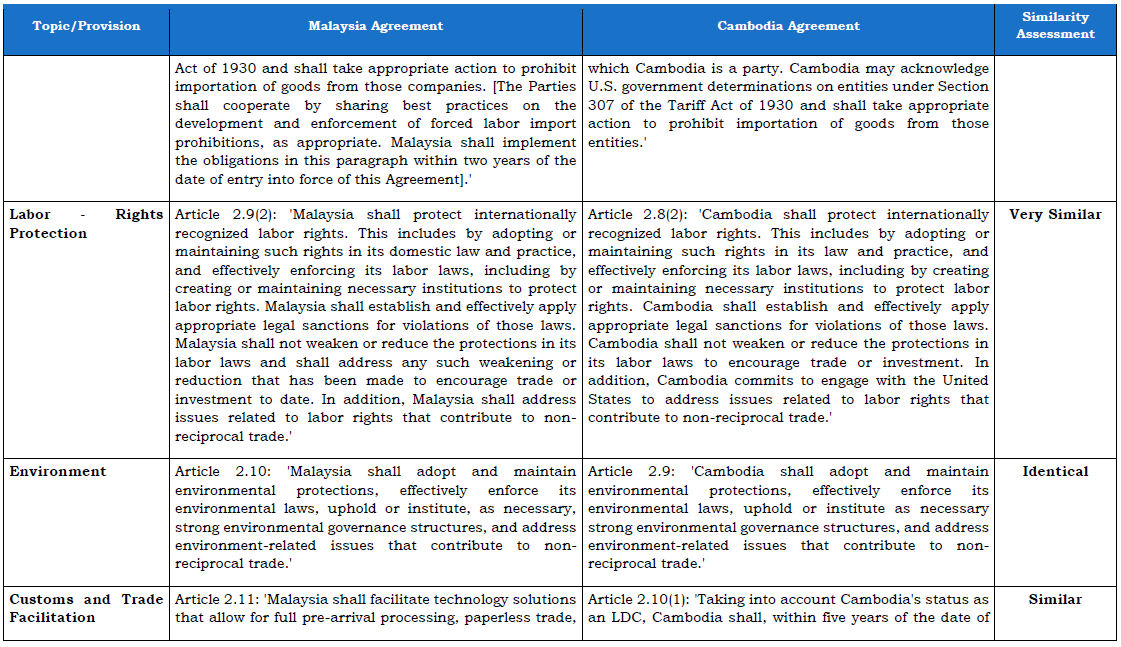

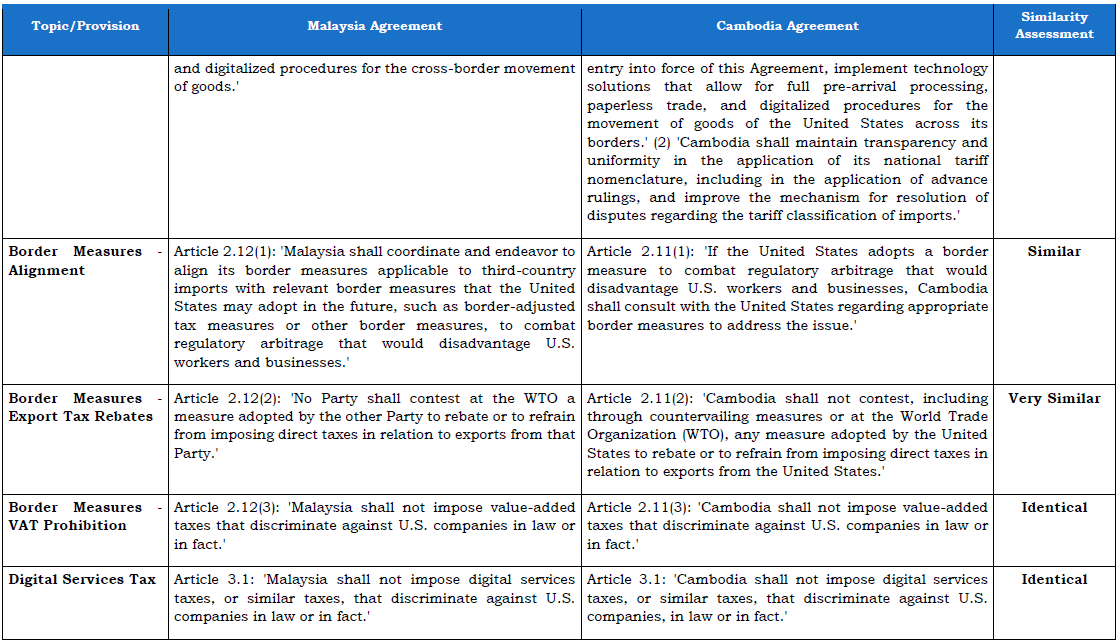

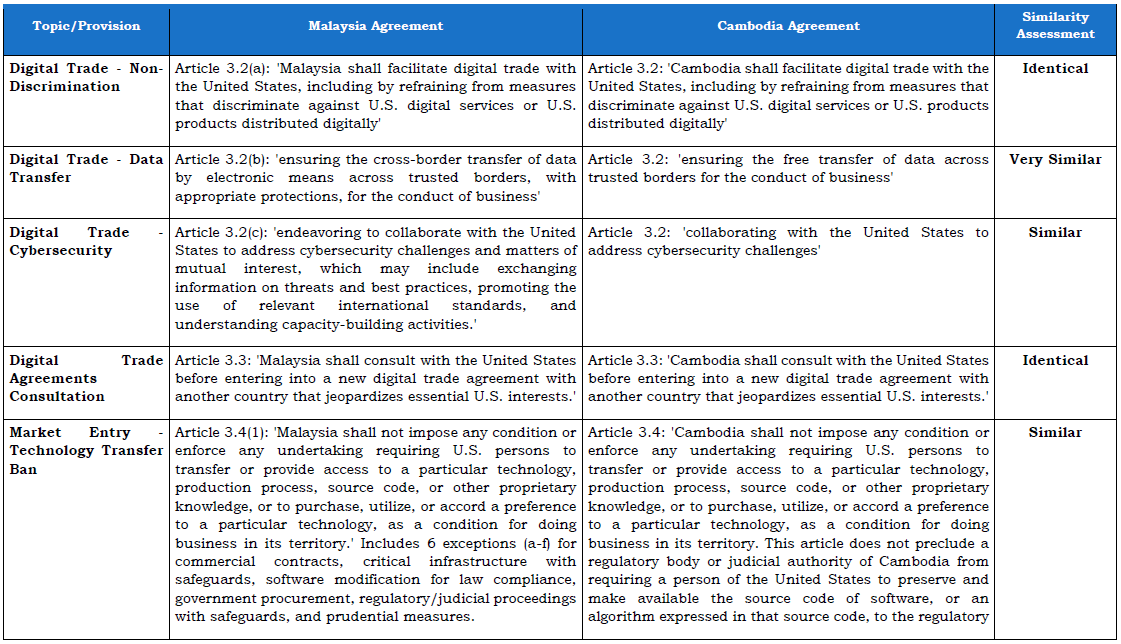

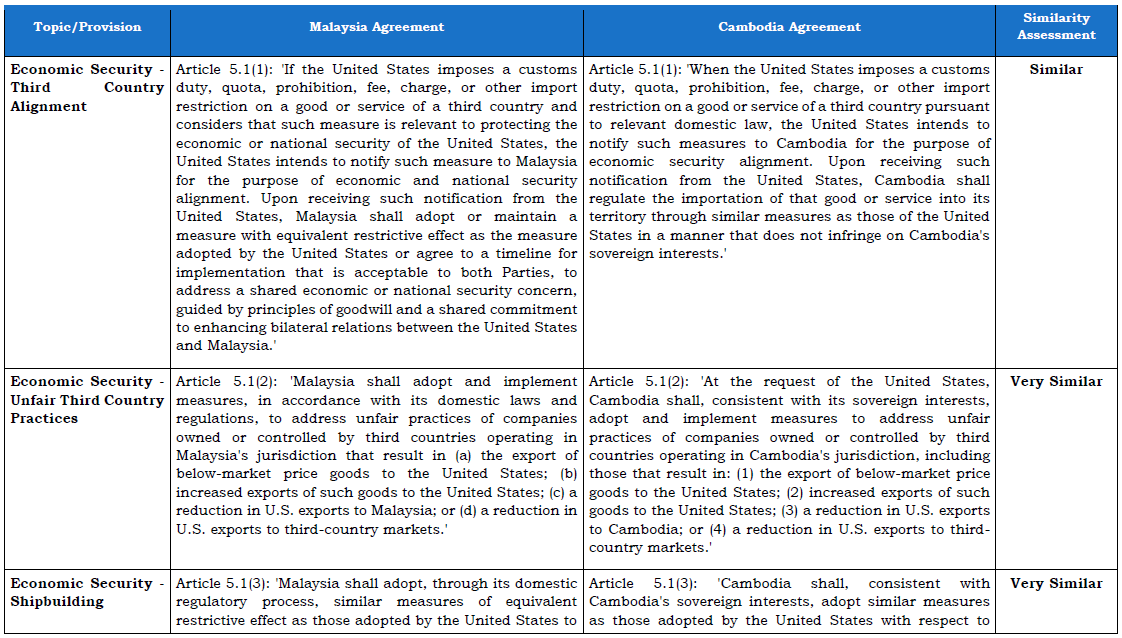

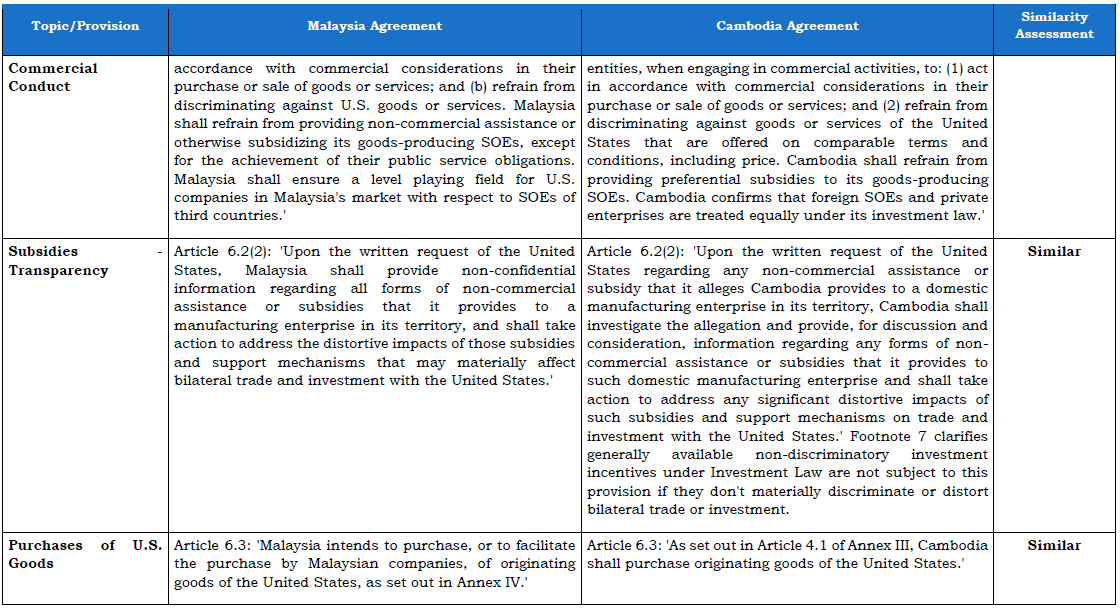

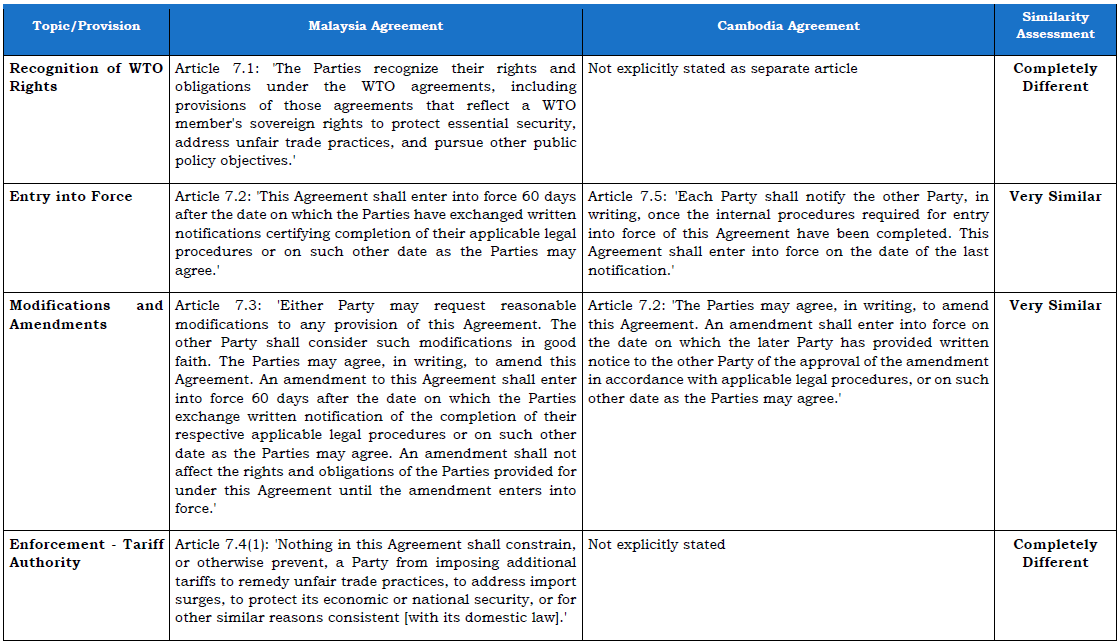

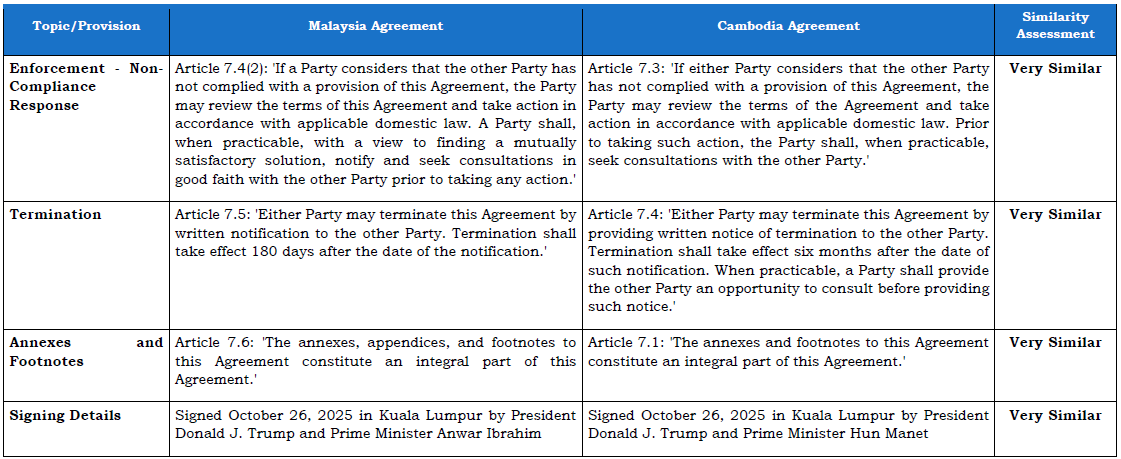

Ahead of the 2025 ASEAN Leaders Summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, four texts were released by the White House relating to trade, investment, and security matters. The full text of two trade accords were released for Cambodia and Malaysia. Progress reports on talks with Thailand and Vietnam were released. What follows are reflections on the texts of the Cambodian and Malaysian trade accords, where more details were provided. A detailed comparison can be found in the pages that follow.

According to the U.S. International Trade Commission’s Dataweb, the combined trade surplus of Cambodia and Malaysia accounted for just 3.1% of the US trade surplus in 2024. In contrast, Vietnam's trade surplus was the third largest of any trading partner with the United States in 2024 and, in numerical terms, is at least three times larger than the combined surplus of Cambodia and Malaysia.

Evidently, the US has prioritised completing negotiations with certain ASEAN countries over others. This outcome may reflect capacity limits on the part of the United States trade negotiation team and possible resistance to terms demanded by the United States on the part of Thailand and Vietnam. It appears that other ASEAN nations are further back in the queue.

There is a material distinction between the treatment of Cambodia, designated a Least Developed Country, and Malaysia. For all its criticism of Special and Differential Treatment at the World Trade Organization, Washington D.C. has accepted that this least developed country commits less in their bilateral accords with the United States. Maybe LDC status will gain greater acceptance as the basis for differentiation in trade accords going forward — as opposed to the WTO norm of self-designated developing country status.

The agreements with Malaysia and Cambodia entrench higher US tariff rates than existed before the current U.S. administration took office. The agreements commit Cambodia and Malaysia to offer preferential market access to the United States, as Peter Harrell has pointed out. Since these accords do not claim to be free trade agreements, others will interpret these tariff moves of Cambodia and Malaysia more negatively — as violations of their MFN tariff obligations at the WTO.

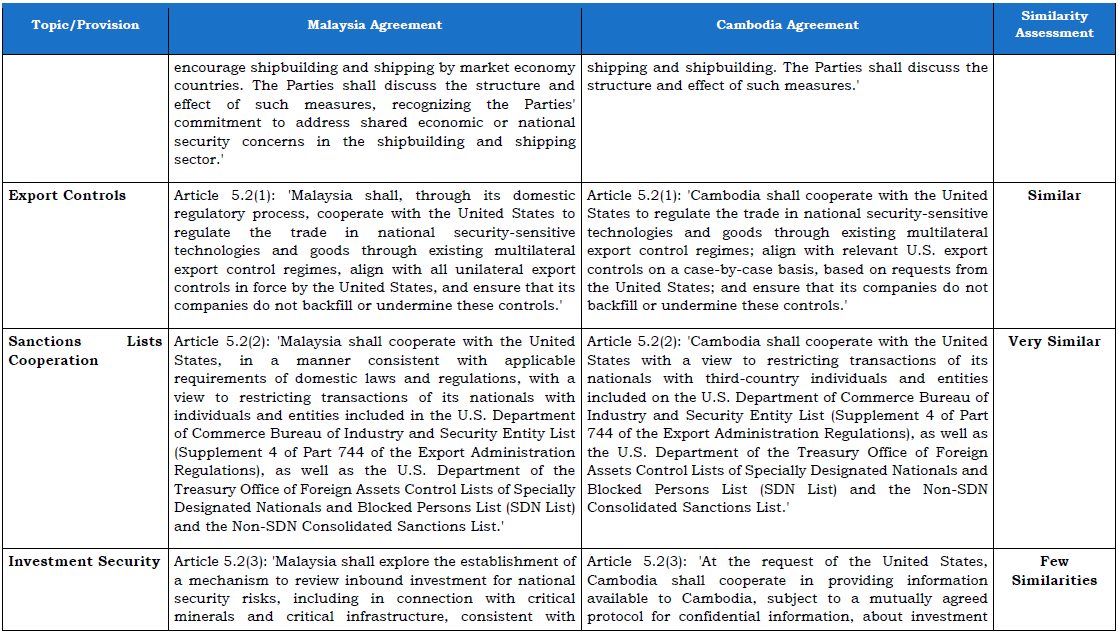

As Wendy Cutler has pointed out, there are no exceptions in the Cambodian and Malaysian accords for tariffs imposed following section 232 investigations by the United States. Rules of origin are mentioned, but there are few specifics. The much-discussed threat to impose transshipment tariffs of 40% were not mentioned in these accords.

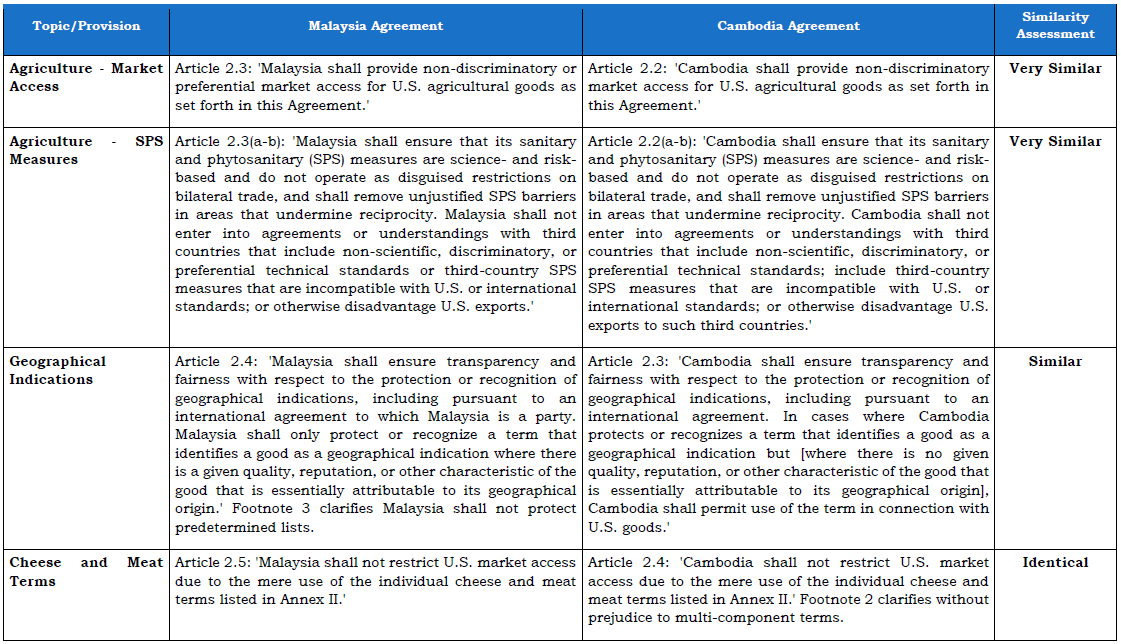

The annexes to both agreements provide further detail as to market access terms and provisions on non-tariff matters. They are worth careful consideration, especially in respect of agricultural goods trade.

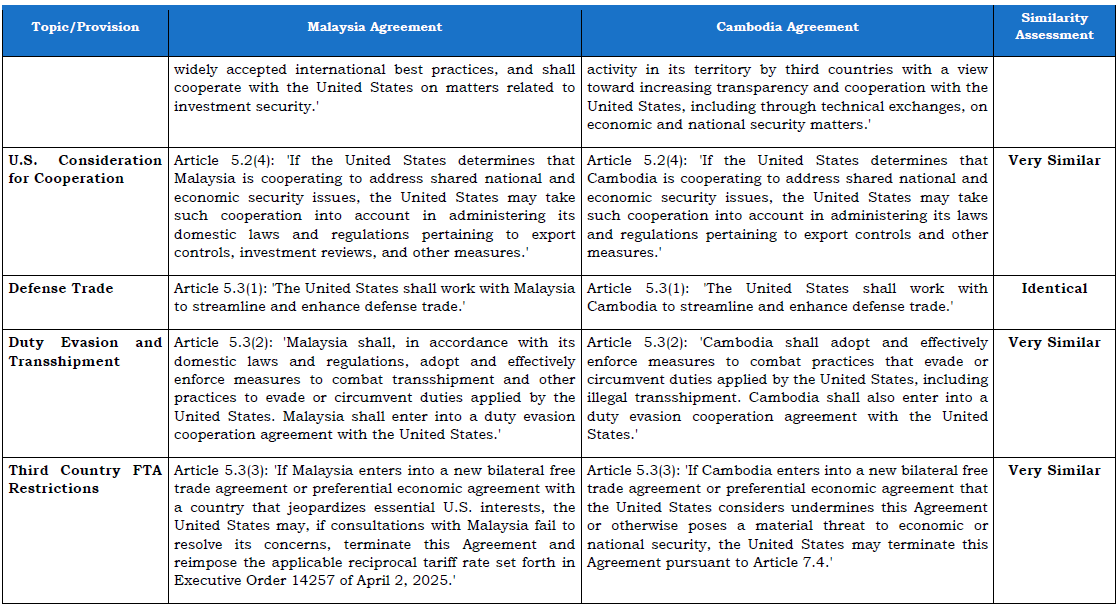

The Malaysian accord commits Malaysian companies to purchase over the next 5 years a total of $150 billion in semiconductors, airplanes, and machinery and equipment for data centres. Cambodia commits to buy at least 10 Boeing 737 planes. Malaysia has committed to “facilitate, to the extent practicable,” a $70 billion investment fund over a 10-year period for firms investing into the United States. While not many details on that fund are available, Malaysia has not given the impression — as Japan did — of creating a fund where investment allocation is dictated by the United States.

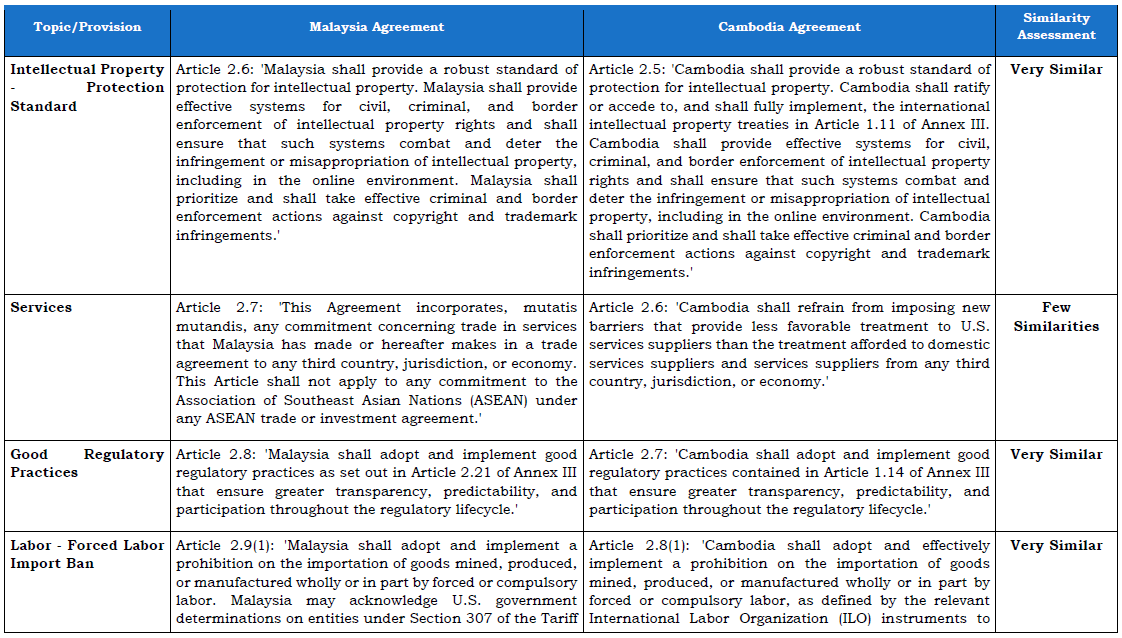

In respect of services commitments, Malaysia committed to extend to the United States any commercially advantageous services commitments that it makes in future agreements with third parties. This amounts to an MFN-plus obligation where Malaysia will extend any market access improvement offered to another country to the United States. Malaysia has also committed to extend to the United States any service market access offering it in any previous free trade agreement. Therefore, this is both a backward-looking and a forward-looking obligation. However, this obligation does not extend to any ASEAN-related accords.

The European Union will be concerned about the provisions in both the Cambodian and Malaysian accords relating to digital sales taxes and signing further digital trade agreements. It looks like Cambodia and Malaysia have committed to align with the position of the United States on such matters. The European Union will be concerned about the provisions on geographical indications and sanitary and phytosanitary standards in both accords.

The security provisions in these agreements will be of concern to the People's Republic of China. Article 5.1(1) of both agreements calls for Cambodia and Malaysia to align with measures taken by the United States against third parties. Let us not forget that since May 2024 Canada and Mexico have raised their import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, at the behest of the United States — this is what alignment means in practice. Article 5.1(2) of both agreements calls upon Cambodia and Malaysia to adopt and implement measures against measures taken by third parties which are said to harm the United States. This commitment relates only to actions taken by third parties and their related entities in Cambodia and Malaysia. Given the extent of Chinese investment in these ASEAN economies, these developments will too be viewed negatively in Beijing.

The agreements with Cambodia and Malaysia commit them to adopt measures with restrictive effect relating to shipbuilding and shipping of goods. This could include instituting port charges on Chinese owned, operated, and built ships that the United States has implemented this month. Both Cambodia and Malaysia have made commitments on inbound foreign investments. The commitments from Malaysia mention consideration of creating a mechanism to review inbound investments. This is a measure which is of concern to the Chinese authorities.

Ultimately, the publication of these Cambodian and Malaysian accords reveals the lengths to which the United States is prepared to use market access as a lever to pull trading partners away from Beijing and Brussels. This leverage varies across countries. Cambodia sends 42% of its merchandise exports to the United States, according to the latest WTO Trade Profiles. In contrast, Malaysia sends just 11.5% of its goods exports Stateside (though some goods shipped to Singapore may reach US buyers).

The question going forward is how much leverage the United States has on account of trade considerations alone. The United States used security leverage to secure lopsided trade accords with the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdom earlier this year. Whether such leverage will be needed for other trading partners remains to be seen.

Simon J. Evenett is Founder of the St. Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade, Professor of Geopolitics & Strategy at IMD Business School, and Co-Chair of the World Economic Forum’s Trade & Investment Council.

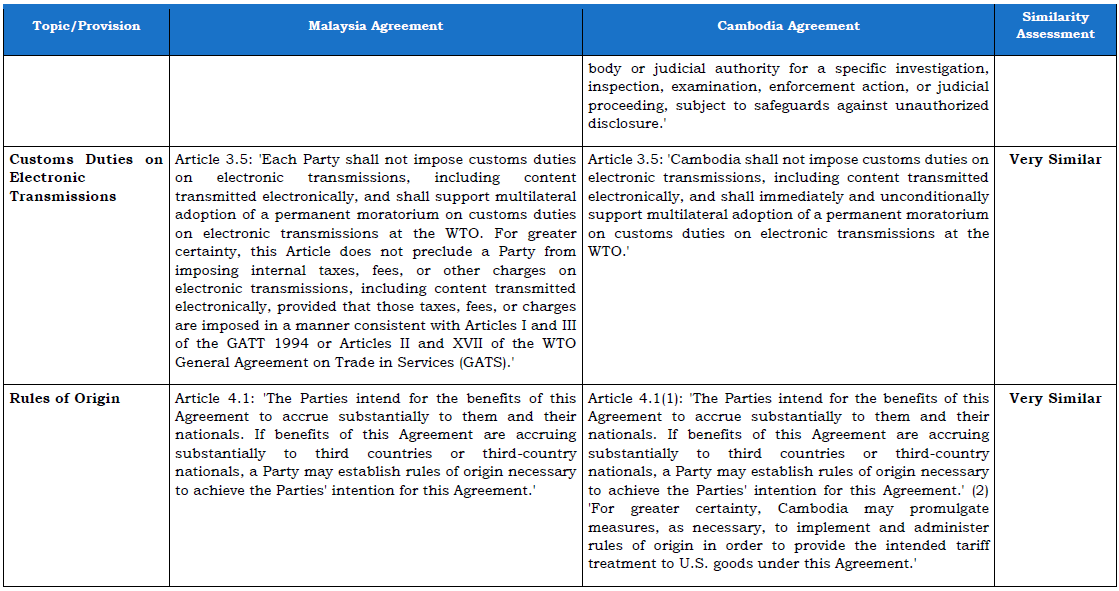

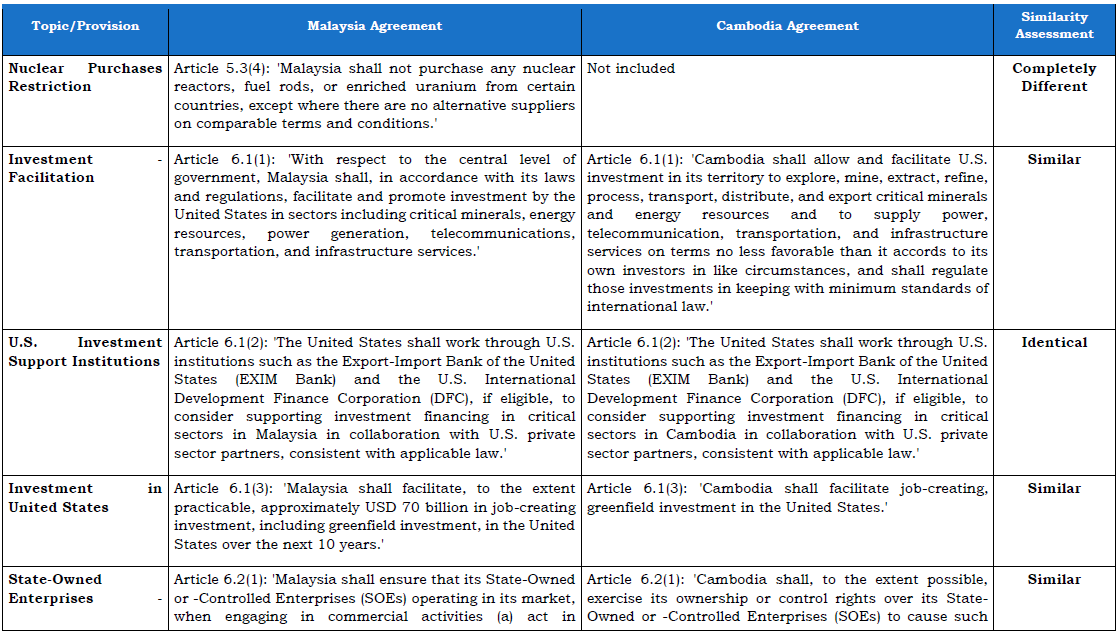

United States - Malaysia vs. United States - Cambodia