Shifting Foundations: The Global Realignment of Defence Industrial Policy

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #68

ZEITGEIST SERIES BRIEFING #68

The 5% of GDP defence spending target recently approved by NATO countries and discussions from the alliance's Defence Industry Forum form a clear signal: increased defence investment has only just begun. This analysis quantifies how governments are rebuilding their defence industries through targeted policy interventions. It reveals three trends: governments outside the NATO alliance are rapidly closing the defence intervention gap with member nations, public procurement to support the defence industry is gaining momentum, and a fundamental misalignment has emerged where NATO prioritises legacy manufacturing while other nations capture next-generation military technologies.

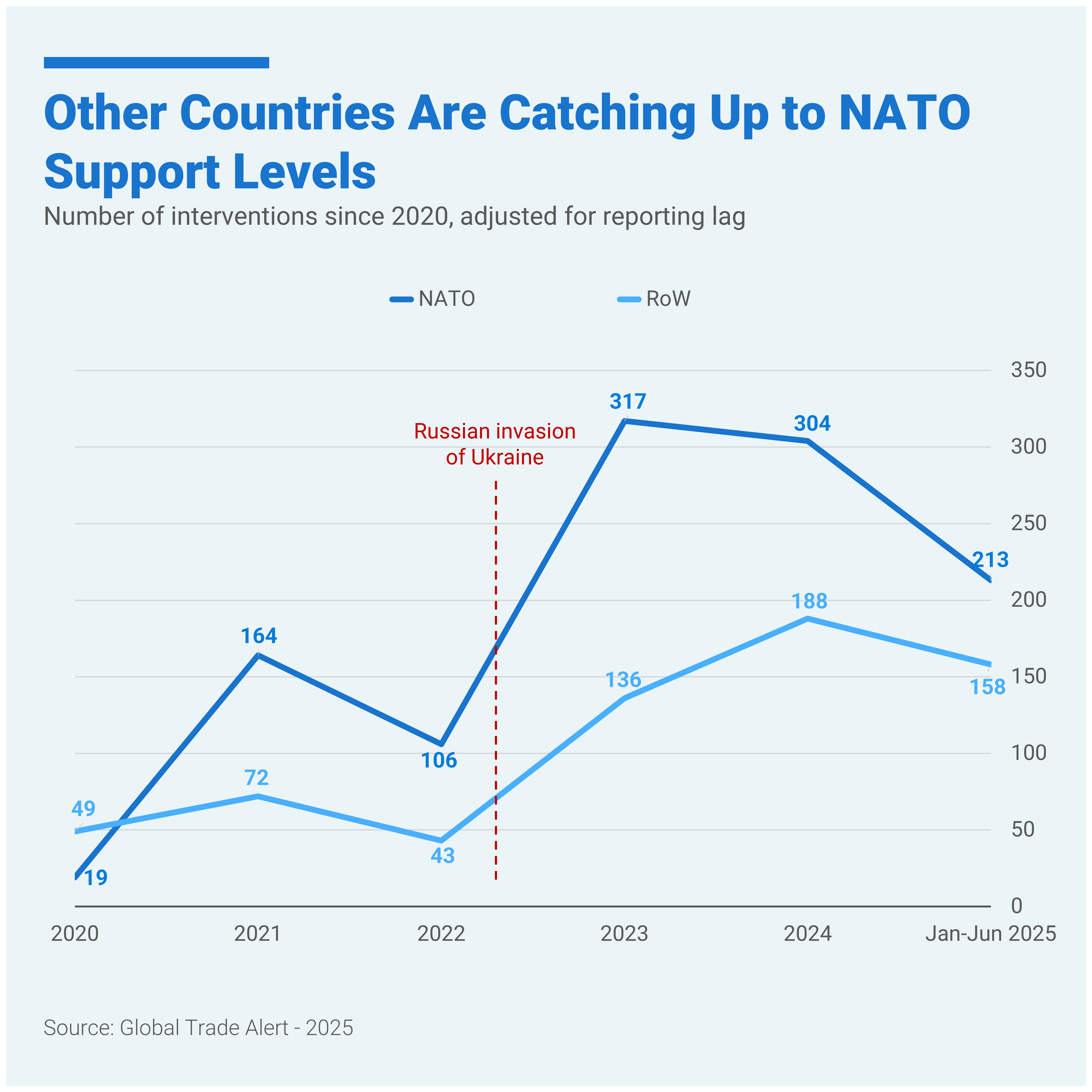

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 reshaped global defence industry mobilisation, with countries worldwide rapidly catching up to NATO's dominant position. Throughout 2020-2025, NATO members maintained higher defence industry intervention levels compared to the broader international community, which includes NATO allies and other nations (see Figure 1). NATO members experienced immediate and dramatic surges in defence interventions during 2023, reflecting the response to regional threats. However, this initial mobilisation appears to have peaked, with NATO support activities now stabilising at elevated but no longer rising levels. In contrast, other governments maintain steady growth in defence support, increasing their collective share from 31% in 2021 to 38% in 2024. At current rates, intervention counts from the wider international community will exceed NATO's by end-2025. NATO's recent initiatives may prove decisive in determining whether the alliance can maintain its defence mobilisation leadership.

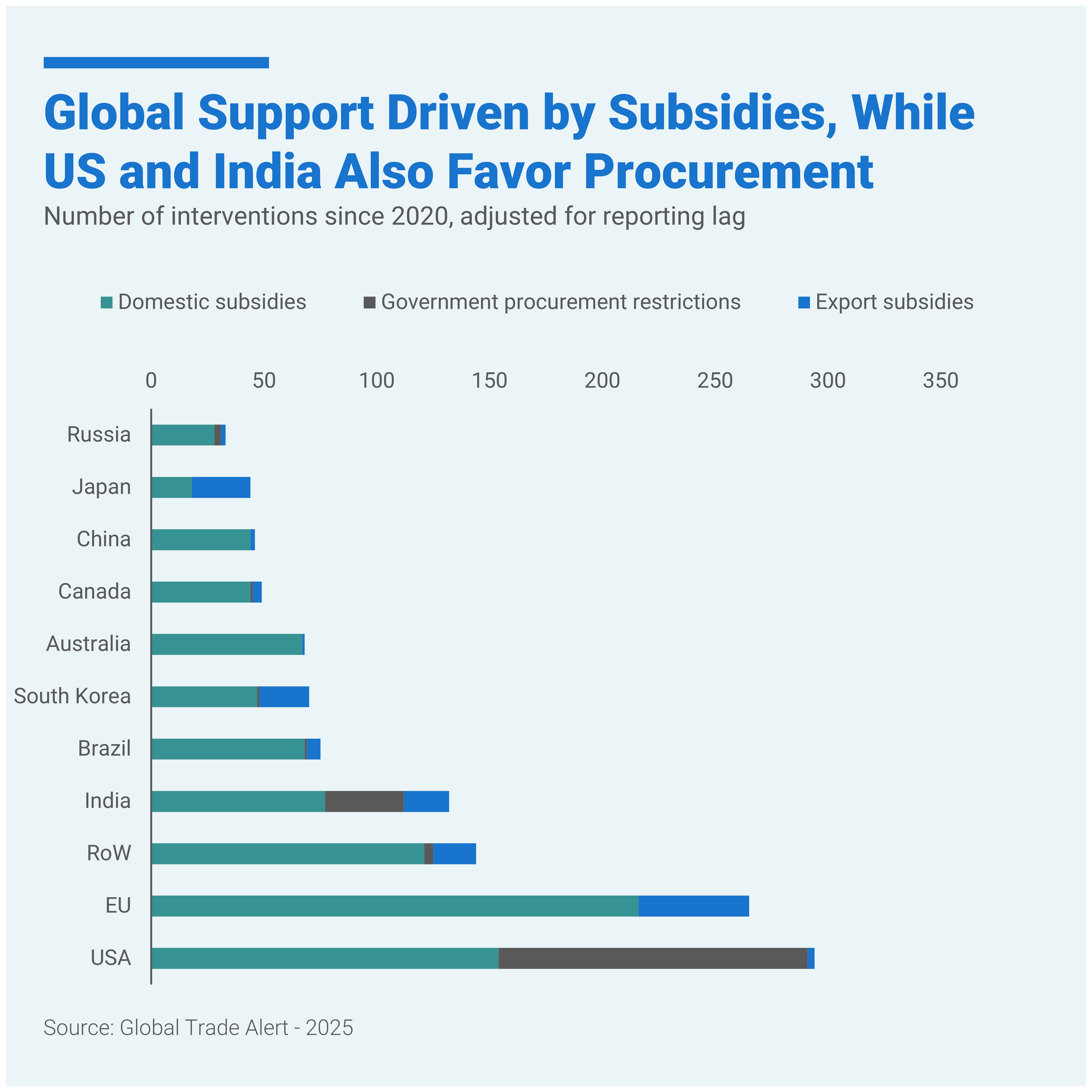

Direct subsidies dominate defence industrial policy, accounting for 70% of interventions across all jurisdictions. The overwhelming preference for financial support reveals an apparent belief that defence industrial capacity requires sustained state intervention. The scale of recent initiatives underscores this trend's magnitude. The EU recently introduced its “ReArm Europe Plan”, mobilising up to EUR 800 billion in funding, whilst the US proposed "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" calls for more federal funding for integrated air defence and missile systems. South Korea, a frequent implementer of export subsidies, also launched a defence industry support package worth KRW 7.4 trillion last year.

Procurement restrictions, previously limited to the US and India, are becoming mainstream policy tools. Since 2020, the US and India have relied on government procurement restrictions as strategic policy instruments for supporting domestic industries (see Figure 2). Washington continues leveraging procurement through a recent Executive Order that mandates federal agencies to prioritise American-made drones. India's Defence Acquisition Procedure 2020 systematically favours domestic suppliers. Beyond these traditional users, European governments are increasingly adopting similar procurement-based policy approaches. The EU's proposed EUR 150 billion loan scheme under the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) includes domestic content requirements. The UK's ten-year industrial strategy published this week identifies defence amongst eight priority sectors, promising to utilise "[the] government's procurement power to create good quality local jobs".

Alliance members concentrate their policy interventions disproportionately on traditional defence goods while ceding ground in next-generation military technologies. NATO's intervention patterns reveal strategic misalignment between resource allocation and contemporary military requirements. Alliance countries account for over 95% of support measures targeting iron and steel products, while maintaining 68% of interventions for conventional weapons, including ammunition, artillery, and missiles. This emphasis on traditional manufacturing contrasts sharply with aerospace military equipment, where other governments control 57% of interventions for helicopters, jet fighters, and satellites, plus 56% for spacecraft and aeroplane components. In aerospace technology, the only notable exemption is drones, where alliance countries account for 65% of interventions. However, total support for this emerging technology remains minimal at only 34 mentions.

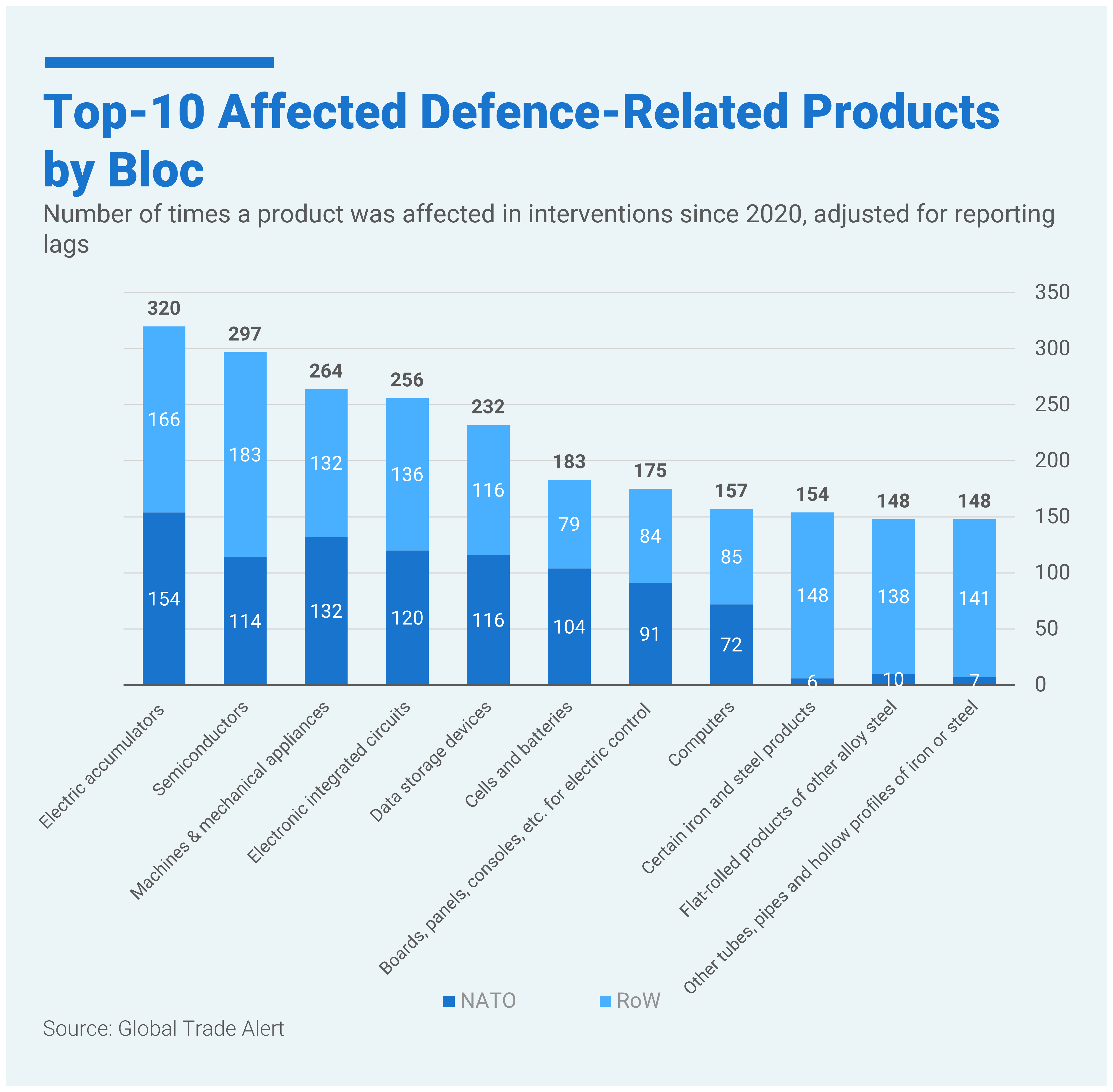

Defence industrial policy increasingly prioritises dual-use technologies essential for modern military capabilities. Data since 2020 reveals stark disparities in technology intervention patterns (see Figure 3). NATO countries account for only 114 interventions (38.4%) supporting semiconductor manufacturing, while other nations contributed 183 (61.6%) measures. Electronic integrated circuits show NATO controlling 46.9% of interventions, while computer technology support reaches only 45.9%. This intervention gap in sectors critical to modern military capabilities reveals how NATO lags behind in supporting dual-use technologies that have emerged as focal points of contemporary defence industrial competition.

The post-2020 defence industrial mobilisation reveals fundamental shifts in global policy approaches alongside strategic misalignment in NATO. The acceleration of procurement restrictions and domestic content requirements across jurisdictions signals heightened economic nationalism in contemporary defence manufacturing practices. Governments are increasingly adopting government procurement policies that favour domestic suppliers, a trend extending beyond traditional users like the United States and India, as they evolve from subsidy-dominated support toward procurement-based industrial strategies. Moreover, NATO's intervention patterns expose strategic misalignment between resource allocation and contemporary military requirements. Alliance countries concentrate support on traditional manufacturing inputs and conventional weapons systems, whereas global trends focus on dual-use technologies. This trend leaves NATO dominating legacy defence production chains while other governments advance in semiconductors, electronic components, and aerospace technologies. The combination of universal procurement nationalism and NATO's technological gaps creates fragmented defence industrial ecosystems where alliance superiority in traditional materials becomes increasingly irrelevant as other countries capture the foundations of modern military power.

Ana Elena Sancho is the Associate Director of the Global Trade Alert.

Fiama Angeles is a Senior Trade Policy Analyst at the Global Trade Alert.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3