ArcelorMittal’s retreat from a flagship green steel project signals deeper trouble for the sector. Once hailed as a climate solution, green steel now faces rising costs, closed markets, and waning political focus. Without scale, stable investment conditions, and sustained policy backing, green steel may never take off.

On June 19, 2025, ArcelorMittal announced it would suspend plans for a green steel project in Germany, citing unsustainable energy costs[1]. This was no minor decision: the project was emblematic of Europe's ambitions to decarbonise its heavy industry, underwritten by billions in public subsidies and framed as a cornerstone of the EU’s Green Deal.

ArcelorMittal’s decision highlights a key tension: political enthusiasm for green steel outpaces the sector’s economic and operational realities, both of which undermine—at this time—the business case for green steel. This piece examines five growing challenges (headwinds) that threaten its viability.

Headwind 1: Climate Loses Priority Amid Geopolitical Reordering

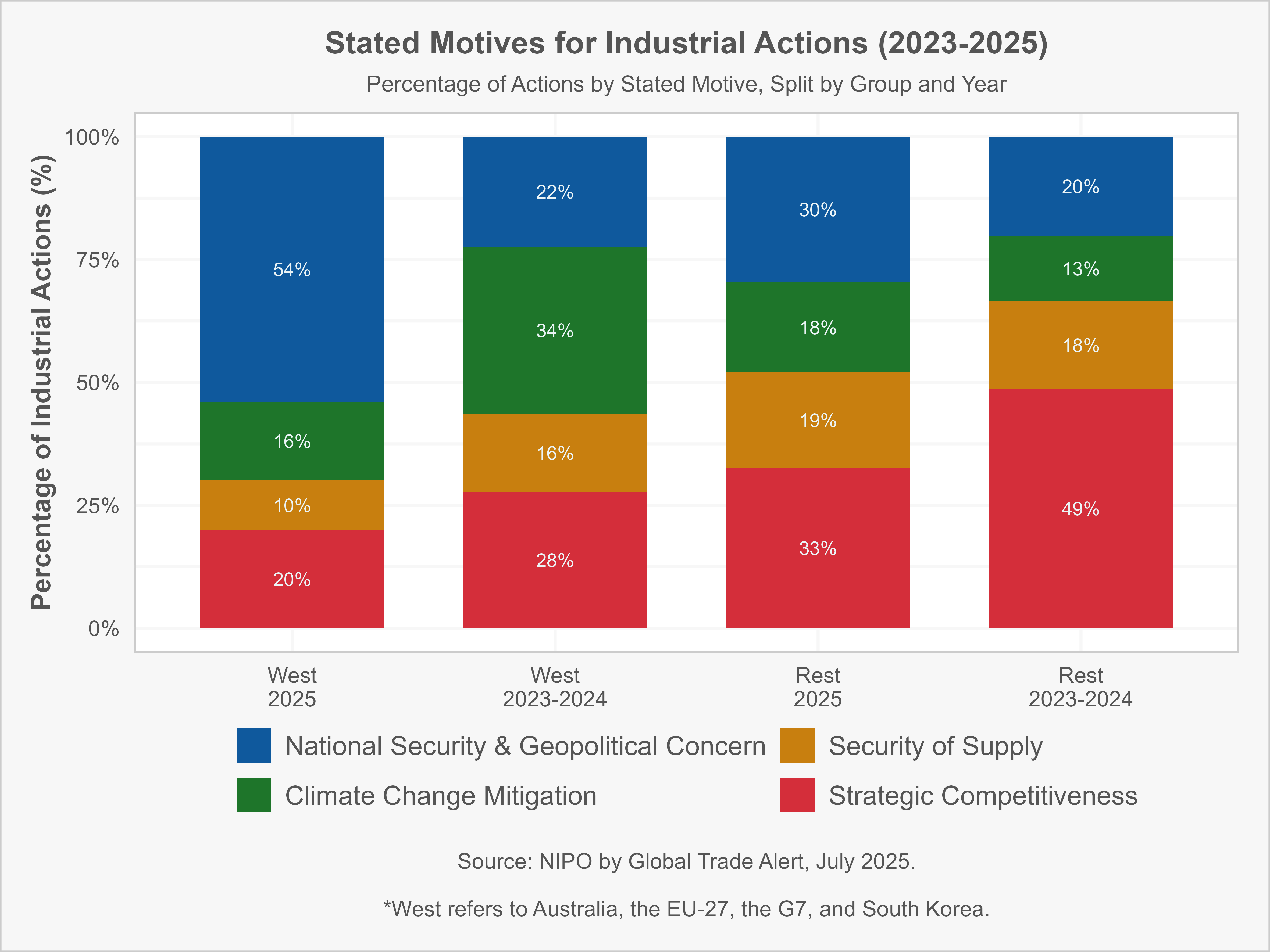

Green steel was originally championed as a pillar of the low-carbon transition. But recent trends show that climate motives are steadily losing ground in Western industrial policy, displaced by concerns over national security. As illustrated in Figure 1, in 2025 only 16% of industrial actions in the West were justified on climate grounds, down from 34% during the 2023–2024 period. At the same time, national security and geopolitical concerns rose sharply in prominence, the stated motive in 54% of actions. Interestingly, while national security considerations are also rising in importance in non-Western countries, the corresponding decline has come from competitiveness-based rationales, not climate change-related objectives.

This shift signals more than a change in rhetoric. When industrial interventions are increasingly justified on strategic or security grounds, climate-oriented initiatives—like green steel—may lose priority in budget allocations, regulatory support, and political attention. The risk is clear: programmes once framed around decarbonisation may be defunded, delayed, or repurposed to serve geopolitical goals instead[2]. Without sustained policy commitment, firms investing in green steel face undue and perhaps unwarranted risks.

Headwind 2: Import Restrictions Shrink—and Fragment—the Addressable Market

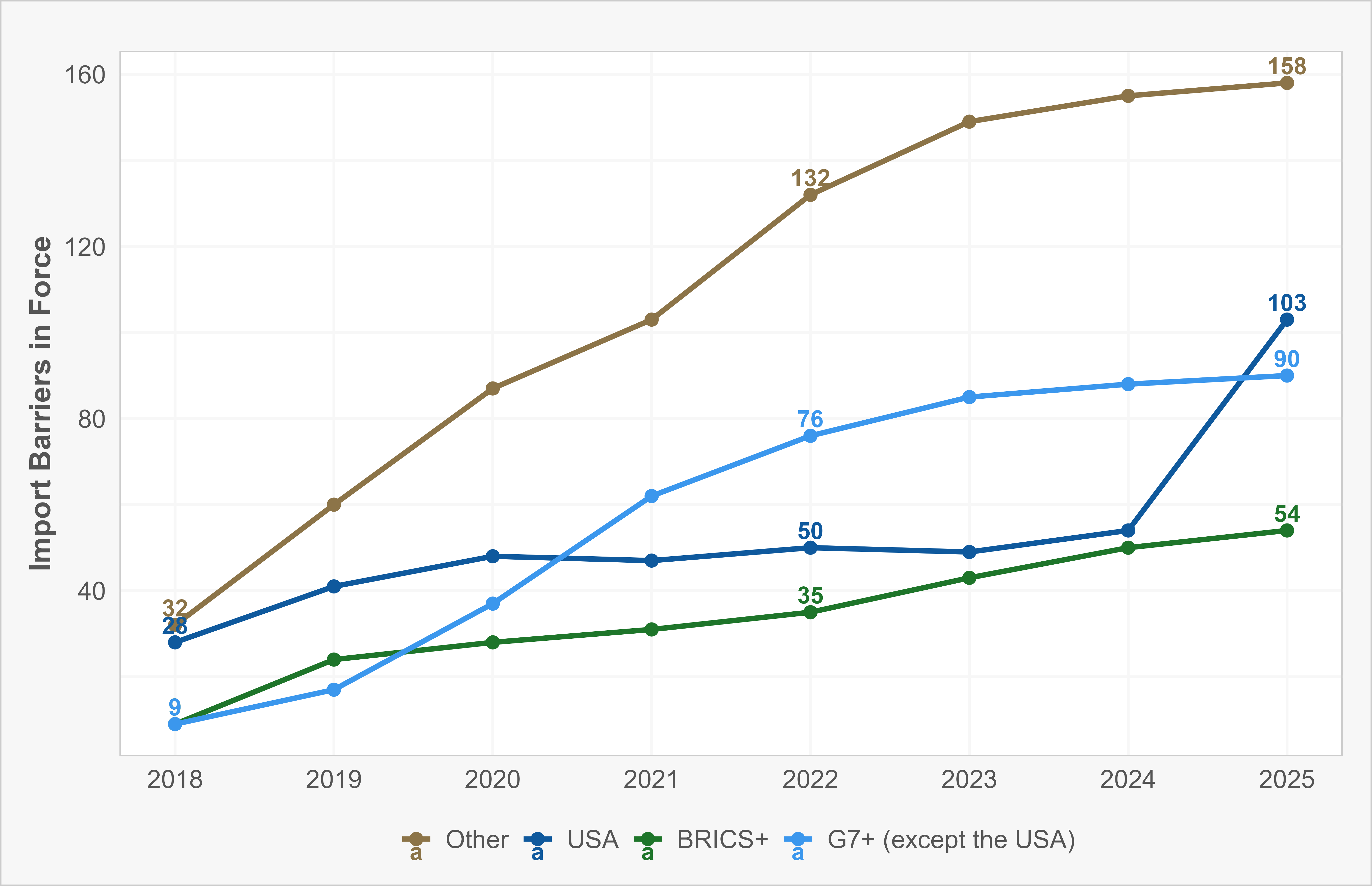

Green steel needs scale to be viable, but domestic markets are closing and global trade is fragmenting. As shown in Figure 2, the number of import barriers has surged, especially in the U.S. and G7 since 2018.

This matters because a firm’s decision to invest in green steel depends on the size and expected growth of the addressable market, which includes both domestic and export opportunities. The high upfront costs of H2-DRI plants or renewable-powered electric furnaces need to spread over as many sales as possible. When trade policy limits that access, expected returns fall and fewer firms engage.

This is especially punitive for producers in mid-sized or developing economies. Brazil, for example, has abundant renewable energy potential but limited domestic steel demand[3]. African countries face a similar bind. Without open access to global markets, green steel remains an unrealised opportunity in the Global South.

Headwind 3: Structural Imbalances Undermine Green Steel Expansion

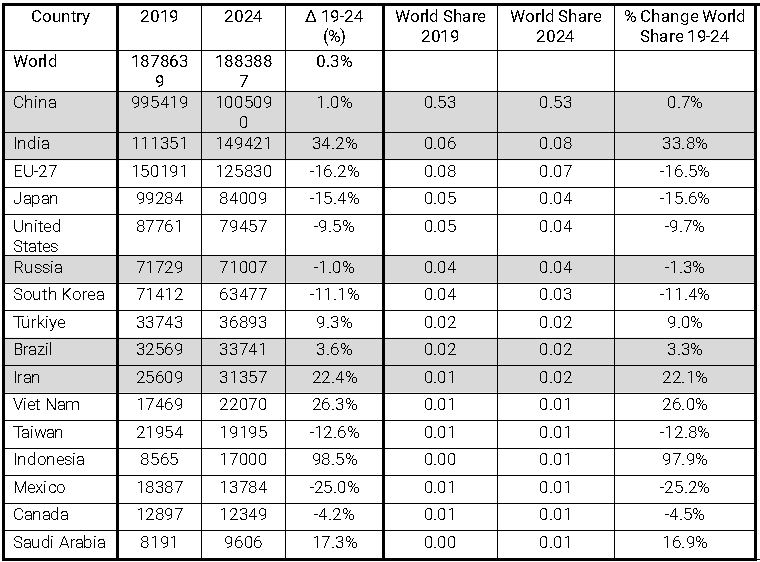

Global steel production and consumption are increasingly misaligned. BRICS+ countries, particularly India and Iran, have raised their share of global output from 66% in 2019 to nearly 70% in 2024 (Table 1). Meanwhile, Western nations face persistent supply shortfalls. In 2023, production-to-demand ratios were below 1 in the EU-27 + UK (0.95), the U.S. (0.90), and Türkiye (0.88), with demand expected to rise further by 2025 (Table 2).

At first glance, this gap seems to offer a strategic opening for green steel to replace carbon-intensive imports and decarbonise domestic supply. Yet in practice, these markets are already served by conventional imports entrenched in legacy trade routes. Despite protectionist policies and increasing demand, Western producers have shown limited appetite for scaling green steel.

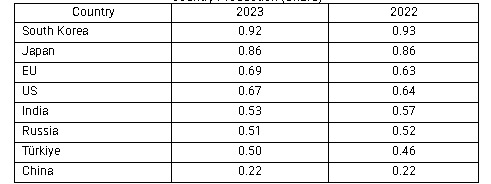

One reason may be structural: Western steel industries often suffer from fragmented production bases too small to support large-scale green investment. Yet Table 3 shows that the top-3 producers in Western countries are highly concentrated—accounting for 69% of production in the EU-27, 67% in the U.S., 86% in Japan, and 92% in South Korea—compared to 22% in China and 53% in India. Moreover, concentration is rising in the EU and U.S., while it is declining in BRICS+, suggesting smaller players are gaining ground there.

This high concentration in Western markets can stifle competition, reduce efficiency, and pose risks to supply and national security. While larger firms have more capacity for green investment, market dominance dampens the incentive to innovate due to limited competitive pressure.

Headwind 4: Rising Capital Costs Undermine Investment in Green Steel

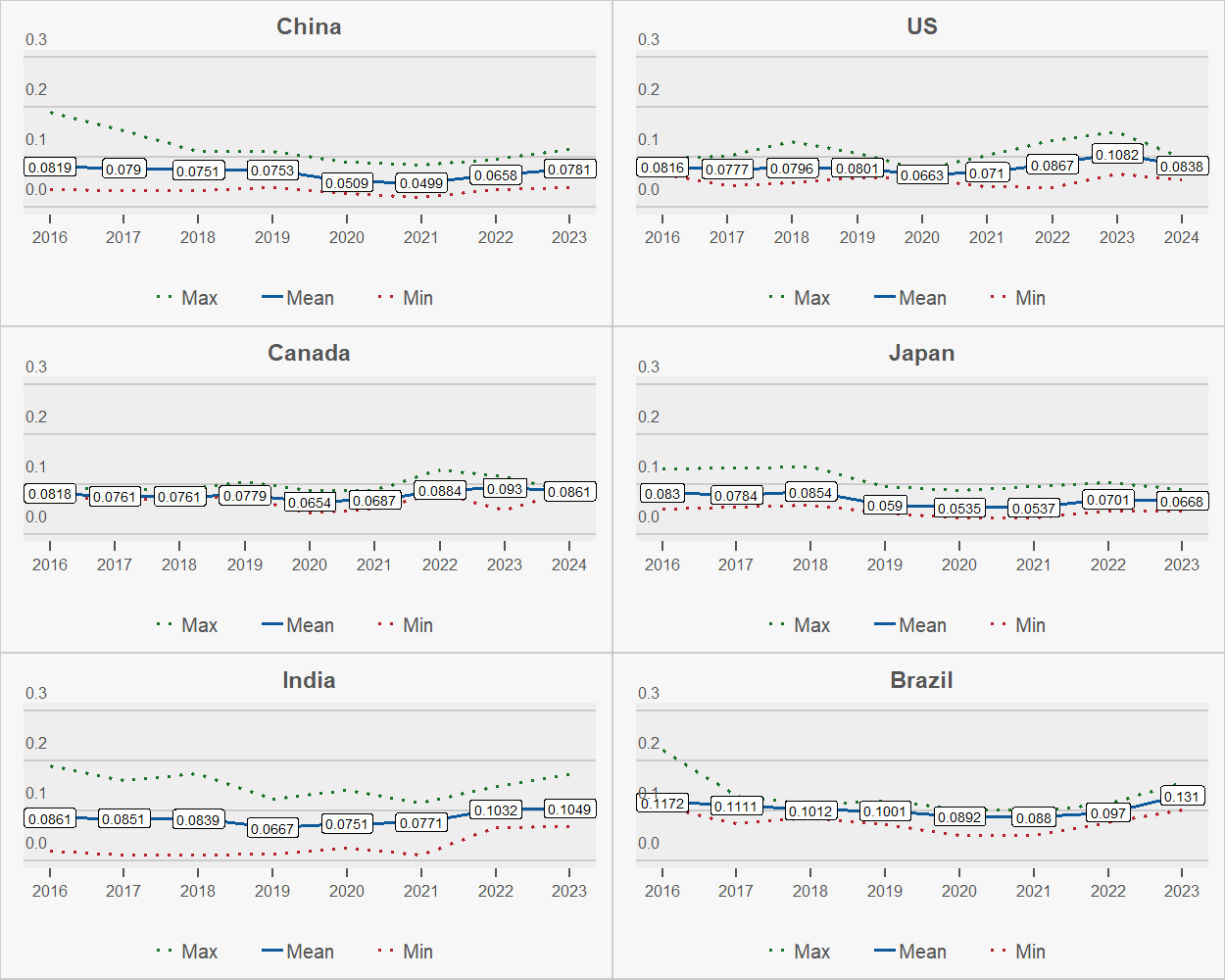

Steel has always been capital-intensive, but green steel raises the bar even higher—with significant upfront costs. In 2025, rising interest rates have driven up the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) across all major steel-producing economies, signalling growing investor caution.

Figure 3 shows that the WACC is particularly high in Brazil and India, reflecting high risk premiums, but even in the U.S. and Canada it now exceeds that of Japan and China. The trend is clear: steel is increasingly seen as a riskier sector.

This is already translating into visible financial stress—with projects postponed, scaled down, or cancelled altogether. Investors are wary, and without reliable policy frameworks or access to low-cost capital, green steel is being treated less as an opportunity and more as a gamble.

Headwind 5: Energy Costs and Volatility

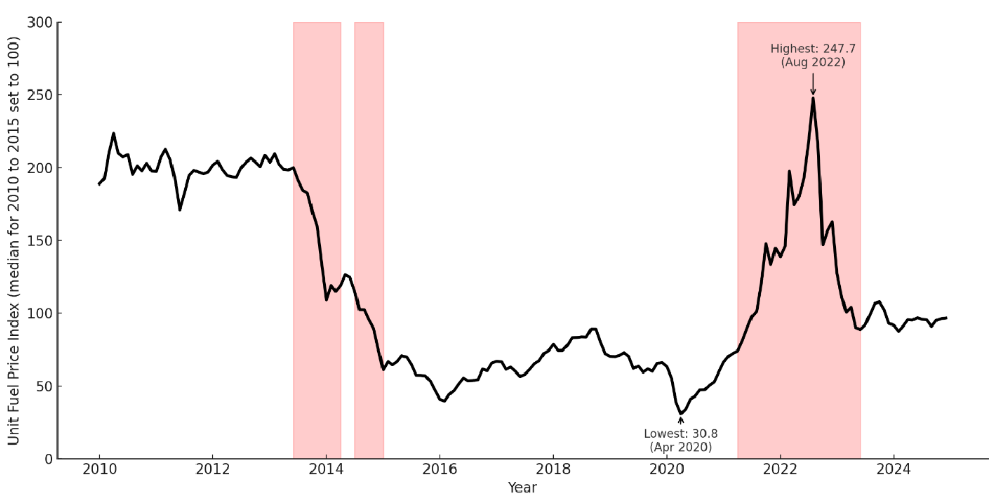

The fifth destabilising headwind is energy cost and volatility. Green steel relies on hydrogen or clean electricity—both of which require vast amounts of energy. Industrial policy may subsidise facility construction, but such state support does not insulate firms from market energy prices

Since 2010, energy prices have swung dramatically. Figure 4 depicts sharp spikes and plunges in cross-border fuel price indices. Several six-month periods saw fluctuations exceeding 50 index points. Such volatility tends to magnify risk.

As ArcelorMittal’s withdrawal from its German green steel project illustrates, even well-funded efforts cannot survive when energy prices render operations commercially unviable.

A Strategic Dream in Jeopardy

Green steel is a strategic sector for the West: it is a way to signal climate leadership, rebuild industry, and challenge the dominance of low-cost producers. But the contradictions in current policy are mounting. Protectionist policies constrain scale. Higher energy costs erode returns. Financial markets hesitate. And the geopolitical repurposing of climate tools undermines policy coherence.

ArcelorMittal’s decision to pull back from its German green steel plans should be seen as a canary in the coal mine. Unless these headwinds are addressed, green steel may become another case of good intentions derailed by political contradictions and commercial realities.

Fernando Martín is an Associate Director at the Global Trade Alert leading the Analytics team.

Figure 1. Shift in Stated Motives Behind Industrial Actions in Western Countries

Figure 2. Import Barriers Covering Steel in Force, by Year

Source: Global Trade Alert (2025)

Notes: Import barriers refer to import bans, import licensing requirement, import monitoring, import quotas, import tariff quotas, internal taxation of imports, other import-related non-tariff measures, and trade defence measures.

Table 1. Production of Crude Steel (Thousands of Tonnes)

Source: Production of Crude Steel in Thousands of Tonnes: https://worldsteel.org/data/annual-production-steel-data/?ind=P1_crude_steel_total_pub/CHN/CHN/IND

Notes: BRICS+ countries are highlighted in grey.

Table 2. Steel Demand Forecasts

Table 3. Market Concentration: Top 3 Producers Steel Production Over Total Country Production (Share)

Figure 3. Weighted Average Cost of Capital of Steel Companies

Source: Crux of Capitalism (2025)

Notes: The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is a financial metric that represents a company's average cost of capital from all sources, including equity, debt, and any other forms of financing. WACC is used to evaluate the cost of financing a company's operations and projects. It takes into account the relative proportions of each source of capital in a company's capital structure, with each source weighted by its proportion.

Figure 4. Two Bouts of Imported Energy Price Instability Have Been Witnessed Since 2013

Source: Evenett, S., & Martín, F. (forthcoming). Public Goals, Private Logic: Industrial Policy’s Revival Amid Headwinds & the Profit Imperative.

Our interest in state support for green steel was stimulated and financed by the European Climate Foundation (ECF).